Harrison Hodges and Martha Agnew were both born into slavery in Mississippi. They married just before the outbreak of war in February 1861. The record of their marriage was handed to the plantation owner, but was lost during the chaos of the war, maybe burned by Sherman’s marching troops. Their only child was born in 1862 and died barely six months later. We will never know why, though it was a common occurrence for slave children, half of whom died before their first birthday. Martha was heartbroken. She would never have the chance to have another baby with her husband.

The Price of Freedom

In 1863, Harrison and Martha were liberated by the Union army. Harrison joined the 11th Regiment USCT and became part of the battle to defeat the Confederacy. Like many black soldiers, he found himself only partly accepted by the white officers who took over his command.

Life as a soldier was tough for Harrison, and most likely difficult for Martha who was left back at home. During this period of the war, Union troops were freeing slaves from southern plantations, but many were soon brought back to work in similar conditions for the military – free, but only just. Their work, picking cotton, keeping the economy running, allowed the Union to keep funding the war effort as much as having soldiers to fight.

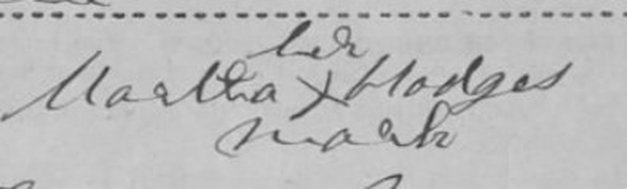

We know very little about what happened to Martha between 1863 and 1867, she disappears from the records. In 1867 however, two years after the end of the war, she applied to claim the pension all war widows were entitled to. Because Martha had been a slave, there was no official record of her marriage. Like other ex-slaves she had to provide pages of evidence and testimony to prove she had indeed been the wife of a soldier. Because Martha could neither read, nor write, her evidence was dictated to a lawyer. She then signed the documents her mark, a large cross. She must have hoped and prayed as the documents were sealed and sent, that the scribblings would convey all the information she had relayed.

Shifting Standards

But the story was not over. In 1874 she was visited by a stocky, yellow-haired, government agent. It had been reported that Martha had remarried and had a child but was continuing to claim her $8 a month as a widow. As the period of Reconstruction came to an end, new laws were being instigated to prevent widows claiming pensions if they remarried for any reason. The gratitude payments to the wives of the dead, were now seen as being an unnecessary burden on the American tax payer.

The fact that such changes in the law were needed, suggests that large numbers of widows were getting remarried. Certainly, many would have felt the pinch without a husband: $8 a month was barely enough to get by, especially with a family to support. Beyond which, there was simply the human need for companionship. What is certain, is that this affected the wives of ex-slaves more than any other group as they were the poorest to begin with and had no property or other assets to bolster their meagre finances. The short lived experiments to give ex-slaves 40 acres and an animal were largely repealed by President Johnson, and the Freedman’s Bureau which helped ex-slaves find work and education, was shut down in 1872. Beyond this the rise of the Ku Klux Klan meant that it was risky to be a black property owner in Mississippi.

Weeks of investigation began into Martha’s marital affairs. She was forced to reveal the most intimate details of her life: that she did not know the father of her child, Eddie; that she had slept with several men, but with no intention of marrying. Nineteenth century moral outrage seemed to extend to sex in a way it had failed to consider slavery problematic. Her friends and acquaintances were all called upon to testify before the inspector was finally satisfied and restarted the pension payments.

Then in 1886, aged 47, Martha was reported once more. Again, she was accused of being married to a man with whom she had another child. Again, the pension was stopped, but this time no claims officer came. The war was now a receding memory, and its widows, especially those from slave origins, were not as important to the business and industrial policies of Grover Cleveland or Ben Harrison. Martha dictated a series of letters to her lawyer; admitting that she had 3 children but declaring that she was still not married. For years, she lived with no pension provision at all whilst the series of exchanges between her and the government office continued. No resolution was reached.

The Fight for Fairness

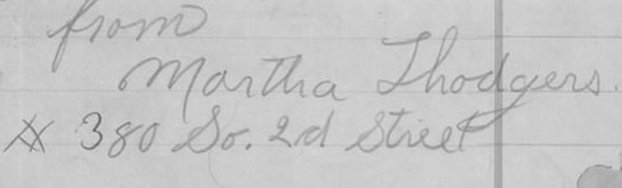

We don’t know what Martha did for support between 1893 and 1911, but there is a large gap in the 150 pages of correspondence. Finally, in February of 1911 Martha sent another letter. This time, the tone was different, more personal, more direct than the legal letters of her lawyer.

Dear Sir,

I thought I would write and let you know my trouble. I need more help for my son. I want to know if you all are going to give us any money. I want to know if you all are going to pay me my pension… I have not went against the laws. My child was born before the laws was brought to me. My last child was 1 year and 1 month when I last got money.

So den… Claim 110.132. Harrison Hodges. Company A of 11th Regt. USCT

I ask the court for mercy.

Help me

| martha_hodges.pdf |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed