This is the third instalment of my blog series “Being proud of our history?”. The question I have been trying to address is whether “the history teacher community” has a good sense of what it has and had not done in relation to challenges raised in recent years, especially in terms of dealing with racism. In this blog I want to look more closely at the discourse of “the community”. Once again I hope this is taken in the spirit of honest reflection and apologise as this is quite a long piece.

The power of discourse

In myprevious blog I explored the ways in which curriculum constructions do not always live up to the self-narrative “the community” has created. However, in making such a statement, I am also aware that not every curriculum construction has engaged deeply with "community" discourse. When Priggs (2020), for example, wrote her excellent article about not just “doing diversity”, it was clear that she was drawing on a rich “community” discourse encountered via conferences and journal articles. It is this discourse I want to explore today.

Academic educational discourse

I want to begin briefly with academic educational discourse. That is to say the books and articles which are part of university level research. At this level, there certainly is a huge amount written. There are numerous studies of how children are impacted by concepts of race, class, gender etc. in the classroom. One book which really shaped my own thinking in this regard was Archer and Francis’ (2007) “Understanding Minority Ethnic Achievement” for example. There are also a range of studies which look at curricular diversity, or explore the ways students encounter specific historical examples of complex concepts. So far, so good.

The power of discourse

In myprevious blog I explored the ways in which curriculum constructions do not always live up to the self-narrative “the community” has created. However, in making such a statement, I am also aware that not every curriculum construction has engaged deeply with "community" discourse. When Priggs (2020), for example, wrote her excellent article about not just “doing diversity”, it was clear that she was drawing on a rich “community” discourse encountered via conferences and journal articles. It is this discourse I want to explore today.

Academic educational discourse

I want to begin briefly with academic educational discourse. That is to say the books and articles which are part of university level research. At this level, there certainly is a huge amount written. There are numerous studies of how children are impacted by concepts of race, class, gender etc. in the classroom. One book which really shaped my own thinking in this regard was Archer and Francis’ (2007) “Understanding Minority Ethnic Achievement” for example. There are also a range of studies which look at curricular diversity, or explore the ways students encounter specific historical examples of complex concepts. So far, so good.

The reality of how this work impacts on "the history teacher community" is however quite different. Despite the wide range of materials available, many are not accessible in schools. This is often because such studies sit behind paywalls and are prohibitively expensive for schools, or else are delivered at conferences which do not reach out to school audiences and often happen during term time. At the same time, academics have little incentive to share their work in teacher publications as universities prioritise the publications which contribute to the “Research Excellence Framework”. There is little kudos in a Teaching History article in the world of most big universities. Although teachers could theoretically access such studies, the chances that they will are low. In addition to this, many of the studies conducted by academics are not immediately accessible to a teaching audience, their findings and implications not easily converted to practice. There is often a divide between the research and the classroom environment.

There are of course exceptions to this rule. The Research Ed movement has tried to include research in a format for schools, but this often involves exceptionally reductive transmission research with a focus on “working out what works” in a fairly generic, pedagogical sense. By contrast, UCL’s Centre for Holocaust education offers a far better example of where academics and those with school experience have come together to create research and to convert it for classroom application, without losing the nuance. Students and teachers work with UCL academics and their research to understand the growth of ideas about “race” and “racism” and are asked to grapple with the roots of antisemitism. This model is very much to be applauded and it is why I think a similar centre for the study of empire and migration would be brilliant. However, for the most part, academic educational discourse has a long way to go to reach out more meaningfully to schools.

Teaching History as “community” discourse

Given so few teachers engage directly with “academic” discourse, I want to turn to more common sources used by “the history teacher community”. For the most part this means teaching conferences and the HA’s Teaching History journal. The notion of “community” thinking being embodied in this journal I think is fairly central to many discussions about history teaching in England, and especially in the new Ofsted frameworks. Indeed, my most recent bulletin from the Historical Association reinforced this notion:

There are of course exceptions to this rule. The Research Ed movement has tried to include research in a format for schools, but this often involves exceptionally reductive transmission research with a focus on “working out what works” in a fairly generic, pedagogical sense. By contrast, UCL’s Centre for Holocaust education offers a far better example of where academics and those with school experience have come together to create research and to convert it for classroom application, without losing the nuance. Students and teachers work with UCL academics and their research to understand the growth of ideas about “race” and “racism” and are asked to grapple with the roots of antisemitism. This model is very much to be applauded and it is why I think a similar centre for the study of empire and migration would be brilliant. However, for the most part, academic educational discourse has a long way to go to reach out more meaningfully to schools.

Teaching History as “community” discourse

Given so few teachers engage directly with “academic” discourse, I want to turn to more common sources used by “the history teacher community”. For the most part this means teaching conferences and the HA’s Teaching History journal. The notion of “community” thinking being embodied in this journal I think is fairly central to many discussions about history teaching in England, and especially in the new Ofsted frameworks. Indeed, my most recent bulletin from the Historical Association reinforced this notion:

“As a charity we are sometimes limited in what we can do immediately, but as part of a history community we can work together to help one another in making the changes we want to see…Over the years we have been helping educators to address more complex and sometimes more uncomfortable histories by engaging with current scholarship and through dialogues that include personal experiences of those in the classroom. We acknowledge that we need to do more and recognise how important [this] is… which is why we will continue to listen to the communities around us and add to the resources here (see below and right) to support teachers seeking to learn more about the issues and to make changes to their practice.”

The idea that “the community” via Teaching History has been tackling issues of diversity in curriculum and enabling students to understand constructs such as racism comes through quite strongly in this bulletin and echoes many of the discussions I have been party to online or at conferences. Although there is recognition that more needs to be done to meet the current challenges, the use of phrases such as “over the years”, “continue to” and “add to” present an overall narrative which suggests the challenge of tackling racism (or other injustices) has always been central to "the community" as embodied by Teaching History. A sense is given that “community” discourse is lighting a path towards better, more inclusive curriculum constructions, if only teachers are “seeking to learn” and engage with it. Whilst I am also hopeful that addressing the current challenges might be addressed through communities of practice, the bulletin is a very clear example of the kind of positive “community” self-narrative we have encountered before. Its claims bear the need for honest reflection and testing.

Being honest about “community” discourse

As I noted in my previous blogs, there have been a number of articles published in Teaching History which have a focus on curricular diversity. Recent examples include Hibbert and Patel’s (2019) work on using Yasmin Khan as a model for teaching a more global Second World War; Trapani’s evidential enquiry about the Silk Road (2019); and Bailey-Watson & Kennett’s (2019) project to add curricular diversity via independent learning. All of these are fantastic pieces of teacher research in their own right.

Even so, a focus on curricular diversity, whilst incredibly welcome it does not fully meet the challenge being put to history teachers: to fundamentally re-think how we get students to engage with concepts of race, colonialism, migration, empire, and a host of other concepts. As of the contributors to the Justice to History podcast put it, thinking curriculum reform is just about adding diverse voices is “trying to Polyfilla the wall”, rather than “knocking the wall down and creating genuine change”. Indeed, the one article from 2019 which goes beyond “diversity” and engages more fundamentally with how we frame curriculum is Mohamud and Whitburn’s (2019) piece on the anatomy of an enquiry.

I don’t for one-minute want to suggest that articles published in Teaching History have not been important in pushing on “community” thinking in many areas of teaching. However, my own record reveals significant gaps in what I have been thinking about and discussing as part of “the community”. Of the four articles I have written for Teaching History since 2014:

Of course, this is just my own writing. What about contributions to Teaching History more widely?

What does a survey of the content of “community” discourse reveal?

By looking at the content of articles published in Teaching History, it should be possible to get a sense of what has been held to be important in “community” discourse and potentially, by extension, “the history teacher community” at large.

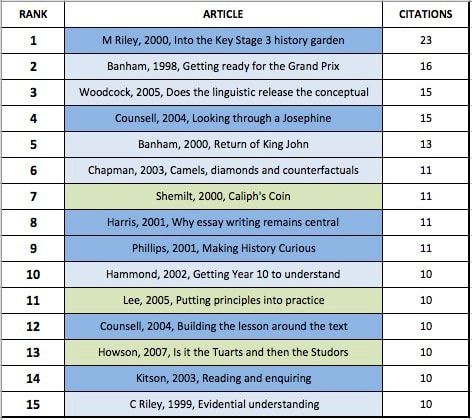

A good starting point is Michael Fordham’s summary of the fifteen most influential articles published in Teaching History from 2004-2013.

Being honest about “community” discourse

As I noted in my previous blogs, there have been a number of articles published in Teaching History which have a focus on curricular diversity. Recent examples include Hibbert and Patel’s (2019) work on using Yasmin Khan as a model for teaching a more global Second World War; Trapani’s evidential enquiry about the Silk Road (2019); and Bailey-Watson & Kennett’s (2019) project to add curricular diversity via independent learning. All of these are fantastic pieces of teacher research in their own right.

Even so, a focus on curricular diversity, whilst incredibly welcome it does not fully meet the challenge being put to history teachers: to fundamentally re-think how we get students to engage with concepts of race, colonialism, migration, empire, and a host of other concepts. As of the contributors to the Justice to History podcast put it, thinking curriculum reform is just about adding diverse voices is “trying to Polyfilla the wall”, rather than “knocking the wall down and creating genuine change”. Indeed, the one article from 2019 which goes beyond “diversity” and engages more fundamentally with how we frame curriculum is Mohamud and Whitburn’s (2019) piece on the anatomy of an enquiry.

I don’t for one-minute want to suggest that articles published in Teaching History have not been important in pushing on “community” thinking in many areas of teaching. However, my own record reveals significant gaps in what I have been thinking about and discussing as part of “the community”. Of the four articles I have written for Teaching History since 2014:

- One has been about progression in substantive and disciplinary knowledge

- One has been about using historical scholarship to establish a framework for a period study

- One has been about wrestling with causal thinking

- One has been about what knowledge-rich teaching might look like

Of course, this is just my own writing. What about contributions to Teaching History more widely?

What does a survey of the content of “community” discourse reveal?

By looking at the content of articles published in Teaching History, it should be possible to get a sense of what has been held to be important in “community” discourse and potentially, by extension, “the history teacher community” at large.

A good starting point is Michael Fordham’s summary of the fifteen most influential articles published in Teaching History from 2004-2013.

What is notable here is that these articles are primarily about the pedagogies involved in teaching second order concepts. Or in other words they are about the “pedagogical how” more than the “curricular what”. The one potential exception is Riley’s “history garden” article which draws on Schools History Project principles and focuses on the process of building a diverse curriculum, as well as the nature of effective enquiry questions. None of the top 15 articles are about the pedagogy or purpose of teaching racism, or gender, or class, or any of a number of other concepts which have shaped, and continue to shape, children’s lives.

Of course, Fordham’s analysis only takes us to 2013 and the advent of the new National Curriculum. I have therefore endeavoured to engage in a similar, though I fear less thorough, study of published content in Teaching History, covering the period from September 2014 to December 2019.* During this period there were 114 articles Published in Teaching History.

Of course, Fordham’s analysis only takes us to 2013 and the advent of the new National Curriculum. I have therefore endeavoured to engage in a similar, though I fear less thorough, study of published content in Teaching History, covering the period from September 2014 to December 2019.* During this period there were 114 articles Published in Teaching History.

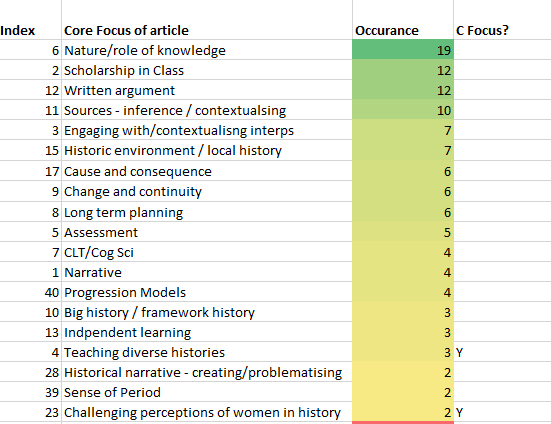

- There were around 50 different core focuses for articles, ranging from assessment, to planning, to change and continuity. Often an article might have a pedagogical and curricular focus, for example, teaching the causes of the rise of the Nazis. In these cases, the primary aim was often to explore the second-order concept, so this was taken as the core focus. The content focuses, unless they were the explicit aim of the piece e.g. “the environment” in Hawkey’s “greening the curriculum”, were noted separately.

- Only 18 core focuses appeared more than once, but some of these received a lot of attention. I have included this list below. There has clearly been much rich discussion in “the community” about the nature and role of knowledge, the role of historical scholarship, and wrestling with written argument. By contrast there were far fewer articles on issues of diversity, and almost nothing written directly about teaching about race or racism as a curricular concept (even cognitive sciences got a greater showing).

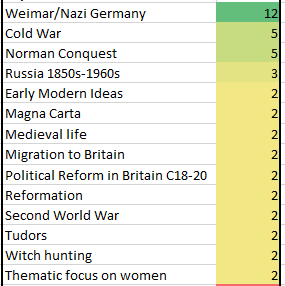

- In terms of topic areas being covered, this was also remarkably more narrow than I had expected. These topics mostly represent the substantive focuses of articles dealing with issues of pedagogy. For example, Hammond's piece on knowledge flavouring claims had a substantive focus on Weimar and Nazi Germany. This is a list of the topic areas which formed part of the published discourse in this period and appeared more than once.

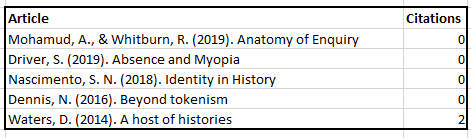

- Of the 114 published articles, just five explicitly dealt with issues or diversity, race, migration or empire. This represents 4% of published output. The articles are listed here for reference and in case I have missed one!

- Mohamud, A., & Whitburn, R. (2019). Anatomy of Enquiry: Deconstructing an Approach to History Curriculum Planning. Teaching History, 177, 28-39.

- Driver, S. (2019). Absence and Myopia in A-Level Coursework: The Intellectual Revolution against Historical Neglect Begins in the Classroom. Teaching History, 174, 62-69.

- Nascimento, S. N. (2018). Identity in History: Why It Matters and Must Be Addressed!. Teaching History, 173, 8-19.

- Dennis, N. (2016). Beyond tokenism: teaching a diverse history in the post-14 curriculum. Teaching History, 165.

- Waters, D. (2014). A host of histories: helping Year 9s explore multiple narratives through the history of a house. Teaching History, 156.

- Of the five articles, most focused on diversity and inclusion in the curriculum; the importance of integrating diverse histories; or sought to spark wider conversations. This is not a criticism but a reflection of the fact that discourse of this sort does seem to be largely absent. Only Mohamud and Whitburn and Driver’s articles directly addressed how we teach complex curricular concepts such as race, or colonialism (In a similar way, there are few articles which deal explicitly with how we teach any complex ideas or concepts e.g. gender, environmental exploitation, or class). I feel Nascimento’s exclamation mark in her article is extremely apt – “the community” really do need to start talking more about identity!

What does a survey of the influence in “community” discourse reveal?

Of course, raw numbers of articles are not the only way to look at what has been important in “the community”. Some articles published in Teaching History receive little further attention beyond publication, but others can have an enormous influence – as can be seen in Fordham’s initial summary. I was therefore interested to look at the influence of articles dealing with diversity, or concepts connected with race, migration, or identity, to gauge their importance in the wider “community” discourse.

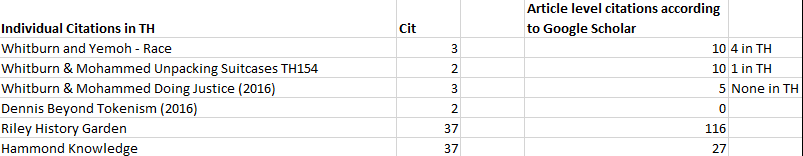

I first looked at the ways in which articles published between 2014 and 2019 continued the discourse of four key pieces on diversity, race, migration and identity published between 2010 and 2016, namely:

- Whitburn & Yemoh’s, ‘My people struggled too’ (2012)

- Mohamud & Whitburn’s, ‘Unpacking the suitcase’ (2014)

- Mohamud & Whitburn’s Doing Justice to History (2016)

- Dennis’, ‘Beyond tokenism’ (2016).

To establish the levels of influence these four articles had on discourse in Teaching History between 2014 and 2019, I chose to count how many times these four pieces were cited in all articles published between during this period. I counted individual citations as I think this gives a clearer sense of the level of influence i.e. if a piece was cited twice in one article, it was counted as two citations.

My results were quite depressing. From my study, I found that none of the four articles listed above was cited more than 3 times in total between 2014 and 2019, and most of these citations happened within a single article. By contrast, Riley’s history garden article (2000), and Hammond’s more recent piece on the knowledge that flavours a claim (2014) were cited 37 times each in the same period.

I also wanted to look at the influence of articles in discourse beyond Teaching History. Using Google Scholar as a rough guide to community discourse, I was able to show a similar pattern in attention paid to the four key articles in this wider field (see the final column above). I also looked at the five key articles published between 2014 and 2020, and dealing with issues of diversity and race, and found that they were barely referenced at all. The figures for this are given below. Depressing indeed.

The issues outlined above are not limited to engagement with the teaching about racism either. There are a whole host of concepts which shape the world children are growing up in which do not seem to receive serious or concerted attention. This was a point Hawkey et al. made when she suggested the need to focus more explicitly on how we help teach the history of the environment (Hawkey, James and Tidmarsh, 2016). How powerful would it be if our curricular conferences and journals were focused on enabling teachers to help pupils grapple with the concepts of race, class, or gender, rather than leaving these things as incidentals on the periphery.

Taking stock

Importantly here, I am not trying to single Teaching History and the Historical Association out for sole criticism. The HA are clearly aware that more needs to be done, and all of us have a part to play in that. It is notable for instance that the Schools History Project have not published much on how we help students to grapple with concepts in the curriculum, despite one of SHP’s principles being to help students understand the world they live in through a study of the past. As a Fellow that is certainly my responsibility.

Any voice in history teaching needs to take stock of where they have done well and where they have fallen short. The current self-narrative is wrong and it has led, for me at least, to a degree of complacency. An investigation of the evidence reveals that my claim that “the community” has been wrestling with issues of race, migration, empire etc. in its discourse is wrong. I think it is worth re-iterating that when, I, or other members of “the community” jump to say that “we are already addressing the challenges of racism and diversity”; we silence those voices who say, “no you’re not” and shut down opportunities to grow.

This has already been a very long blog, so I will lay down three challenges.

* I have chosen to focus on published articles rather than editorial pieces, as these are more commonly viewed as the backbone of the discourse, and to match Fordham’s approach

References

Taking stock

Importantly here, I am not trying to single Teaching History and the Historical Association out for sole criticism. The HA are clearly aware that more needs to be done, and all of us have a part to play in that. It is notable for instance that the Schools History Project have not published much on how we help students to grapple with concepts in the curriculum, despite one of SHP’s principles being to help students understand the world they live in through a study of the past. As a Fellow that is certainly my responsibility.

Any voice in history teaching needs to take stock of where they have done well and where they have fallen short. The current self-narrative is wrong and it has led, for me at least, to a degree of complacency. An investigation of the evidence reveals that my claim that “the community” has been wrestling with issues of race, migration, empire etc. in its discourse is wrong. I think it is worth re-iterating that when, I, or other members of “the community” jump to say that “we are already addressing the challenges of racism and diversity”; we silence those voices who say, “no you’re not” and shut down opportunities to grow.

This has already been a very long blog, so I will lay down three challenges.

- We need to continue to engage with work around diversity in curriculum. We have come a long way in this regard since Teaching History was first published in 1969, but there is much further to go. We have good models for this. But we also need to recognise that this is more than just curricular diversity.

- As teachers, I think we need to think carefully about the concepts which have shaped us historically and continue to shape young people’s lives and experiences. So often just a handful of concepts are explored in depth in schools, “the nation” often being foremost in these. This is not sufficient. As teachers we need to rise to the current challenge and consider how we help students develop a grounded understanding of: race, migration, empire and colonialism over time. However, we also need to consider other important concepts: faith and religion, family and kinship, class, ideas, political ideologies, the economy, material culture, gender, sexuality and of course, nation, and how we develop students' understanding of these too.

- We do have a good starting point and models to begin a meaningful study of how we engage with the concepts listed above. The UCL Centre for Holocaust Education is a gold standard, but we don’t have to wait for similar centres to take action (though this is also a call for academics to bring the discussions they are already having into conversation with the needs of teachers in schools). There is definitely a will for “community” discourse to be more inclusive, the challenge then is for history teachers to start exploring some of the concepts listed above, to engage with what has been written, both in academic circles and in Teaching History, and move the discourse on. As Nick Dennis pointed out in a recent blog, we need deeds not words; but in this instance, the deeds might well need to be words.

* I have chosen to focus on published articles rather than editorial pieces, as these are more commonly viewed as the backbone of the discourse, and to match Fordham’s approach

References

- Archer, L. and Francis, B. (2007) Understanding minority ethnic achievement: race, gender, class and ‘success’. London ; New York: Routledge.

- Bailey-Watson, W. and Kennett, R. (2019) ‘“meanwhile, elsewhere…”: harnessing the power of community to expand students’ historical horizons’, Teaching History, (176), pp. 36–43.

- Dennis, N. (2016) ‘Beyond tokenism: teaching a diverse history in the post-14 curriculum’, Teaching History, (165), pp. 37–41.

- Hammond, K. (2014) ‘The knowledge that “flavours” a claim: towards building and assessing historical knowledge on three scales’, Teaching History, (157), pp. 18–24.

- Hawkey, K., James, J. and Tidmarsh, C. (2016) ‘Greening the curriculum? History joins “the usual suspects” in teaching climate change’, Teaching History, (162), pp. 32–41.

- Hibbert, D. and Patel, Z. (2019) ‘Modelling the discipline: how can Yasmin Khan’s use of evidence enable us to teach a more global World War II?’, Teaching History, (177), pp. 8–15.

- Mohamud, A. and Whitburn, R. (2014) ‘Unpacking the Suitcase and Finding History: Doing Justice to the Teaching of Diverse Histories in the Classroom’, Teaching History, (154), pp. 40–46.

- Mohamud, A. and Whitburn, R. (2016) Doing justice to history: transforming black history in secondary schools.

- Mohamud, A. and Whitburn, R. (2019) ‘Anatomy of enquiry: deconstructing an approach to history curriculum planning’, Teaching History, (177), pp. 28–41.

- Priggs, C. (2020) ‘No more “doing” diversity: how one department used Year 8 input to reform curricular thinking about content choice’, Teaching History, (179), pp. 10–19.

- Riley, M. (2000) ‘Into the Key Stage 3 history garden: choosing and planting your enquiry questions’, Teaching History, (99), pp. 8–13.

- Trapani, B. (2019) ‘Who can tell us the most about the Silk Road? Historical scholarship, archaeology and evidence in Year 7’, Teaching History, (177), pp. 58–67.

- Whitburn, R. and Yemoh, S. (2012) ‘“My People Struggled Too”: Hidden Histories and Heroism--A School-Designed, Post-14 Course on Multi-Cultural Britain since 1945’, Teaching History, (147), pp. 16–25.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed