Back to main blog

5. What impact did non-specialist teaching have on grade stability?

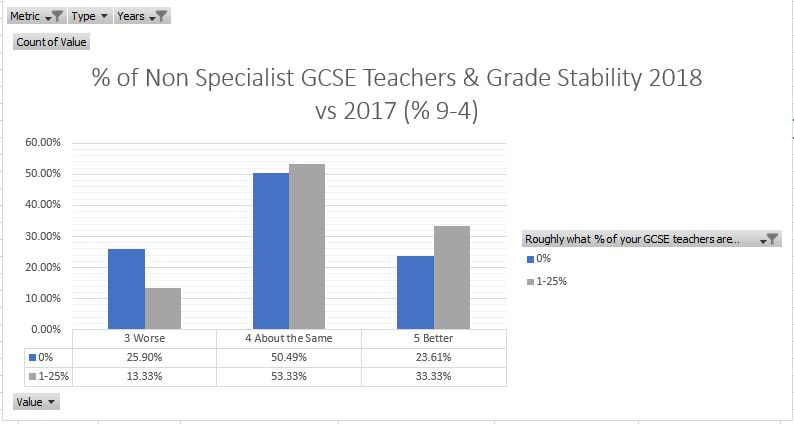

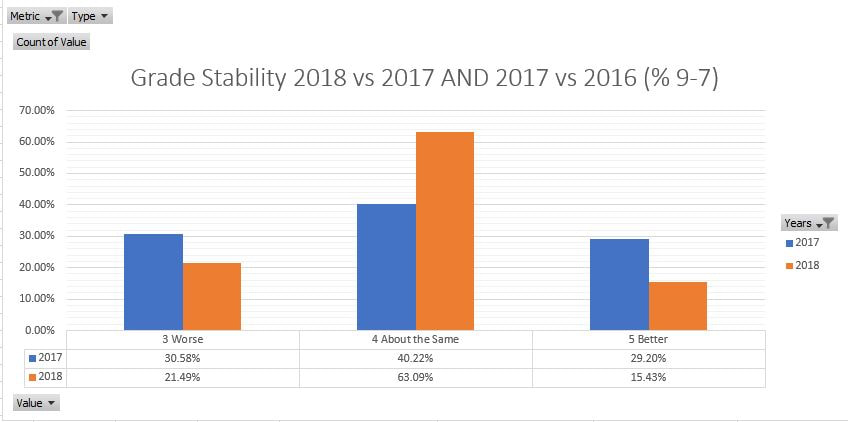

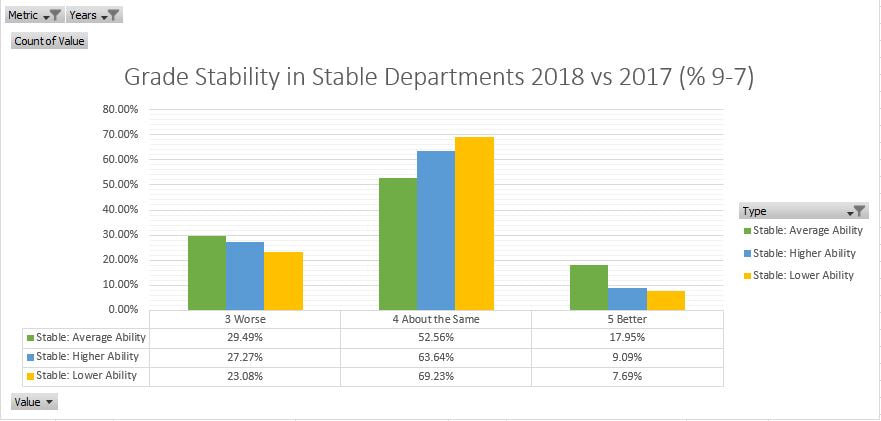

This is one of the most interesting, and runs somewhat counter to what I was expecting. If we look at the correlation between departments with no non-specialists and result stability in 2018, we find that there is a slight disadvantage. There are of course many reasons which could account for this: the department might be very tightly run; the non-specialists may actually have taught for a long time; the specialists might have over-taught recycled content areas from old specs etc. It is also worth saying that only a handful of departments in the sample had non-specialists teaching at GCSE, and then in small numbers. A single positive result might therefore skew this data a lot.

5. What impact did non-specialist teaching have on grade stability?

This is one of the most interesting, and runs somewhat counter to what I was expecting. If we look at the correlation between departments with no non-specialists and result stability in 2018, we find that there is a slight disadvantage. There are of course many reasons which could account for this: the department might be very tightly run; the non-specialists may actually have taught for a long time; the specialists might have over-taught recycled content areas from old specs etc. It is also worth saying that only a handful of departments in the sample had non-specialists teaching at GCSE, and then in small numbers. A single positive result might therefore skew this data a lot.

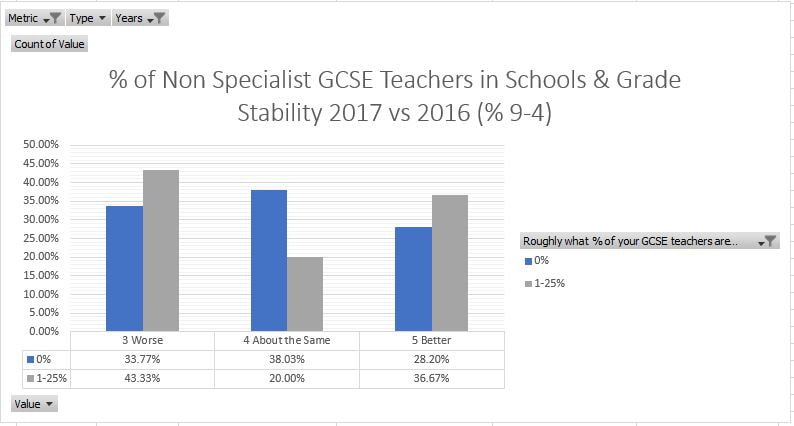

What is most interesting is where this is compared to 2017 vs 2016 grade stability. Here the impact of non-specialists seems to make results much more erratic. This may suggest that the new GCSE has levelled the playing field between specialists and non-specialists somewhat whilst expertise is rebuilt.

Takeaway: This is hard to call, and I am not sure there are any lessons here. However, there is definitely need for some further investigation into the impact of non-specialist teaching on results. If the specialist teaching does not correlate to better outcomes, that seems like a worrying state of affairs.

Back to main blog

Back to main blog

RSS Feed

RSS Feed