This is part 1 of my blog series on choosing good history textbooks. You can find the main page HERE.

One key aspect of a good history textbook or textbook series is the core narrative it develops. The best textbooks in my opinion have good extended prose, flow well, read aloud well, and have people's individual stories woven through them. A good textbook creates an engaging narrative which children enjoy engaging with.

Over the last couple of years, Robert Peal has written a number of pieces criticising history textbooks for lacking clear narrative and for being broken down into tiny chunks. As a proponent of the Annales approach to history, I am also a great lover of overarching narratives, though I suspect somewhat different ones to Peal.

The call for clear narrative was also an important message which came out of the West London Free School History Conference, held on 25 February 2017. Counsell for instance noted that having a good grounding in historical knowledge is an issue of social justice. She also referred back to her long-standing plea to think about the fingertip and residue knowledge we develop as part of our individual curricula. To an extent therefore I agree with Peal's point (though not his critique) that a good set of textbooks needs to have solid coverage of British history as an absolute minimum (what else should be covered is of course a matter for debate).

One key aspect of a good history textbook or textbook series is the core narrative it develops. The best textbooks in my opinion have good extended prose, flow well, read aloud well, and have people's individual stories woven through them. A good textbook creates an engaging narrative which children enjoy engaging with.

Over the last couple of years, Robert Peal has written a number of pieces criticising history textbooks for lacking clear narrative and for being broken down into tiny chunks. As a proponent of the Annales approach to history, I am also a great lover of overarching narratives, though I suspect somewhat different ones to Peal.

The call for clear narrative was also an important message which came out of the West London Free School History Conference, held on 25 February 2017. Counsell for instance noted that having a good grounding in historical knowledge is an issue of social justice. She also referred back to her long-standing plea to think about the fingertip and residue knowledge we develop as part of our individual curricula. To an extent therefore I agree with Peal's point (though not his critique) that a good set of textbooks needs to have solid coverage of British history as an absolute minimum (what else should be covered is of course a matter for debate).

|

|

How well is the core narrative developed?

The first question I asked of the 'Knowing History' series was how well it developed the core narrative of the book. To do this, I looked at the second book in the series, which covers the period 1509-1760. A sample chapter of this book is available online via Collins.

In terms of the text itself, it is well written and flows naturally within each chapter. The language used is also very ambitious, which is to be applauded. There is no shying away from terms such as “intercession” or “Indulgences”, again something I think more textbooks publishers should promote. Sadly however some terms are left for students to look up in the glossary, rather than having in-text or contextual explanations.

I did experiment with reading the book aloud and found it to be passable. The story jumps around a bit in different sections, but there are certainly chapters which flow extremely well. There are also a range of stories woven into the text. Sadly, many of these seem to be from a very small and exclusive group at the top of society.

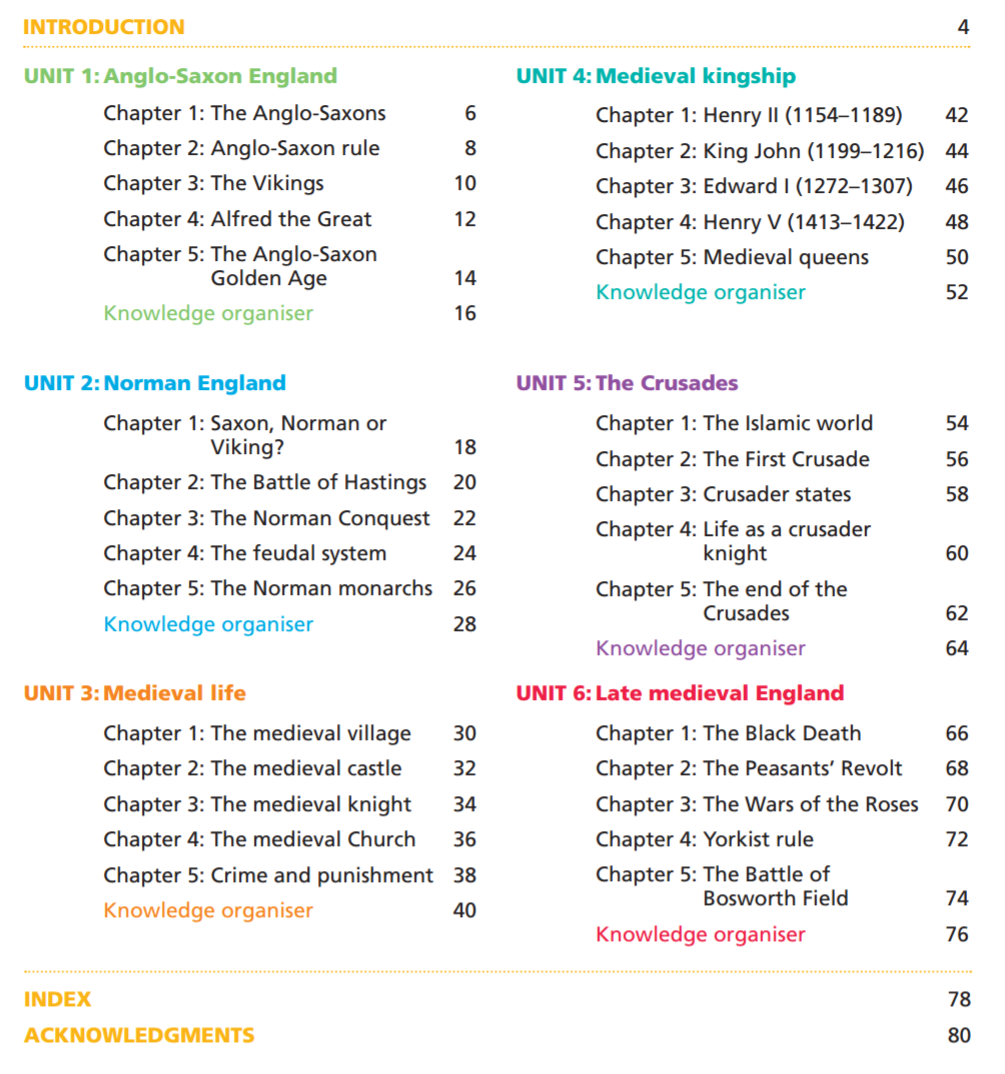

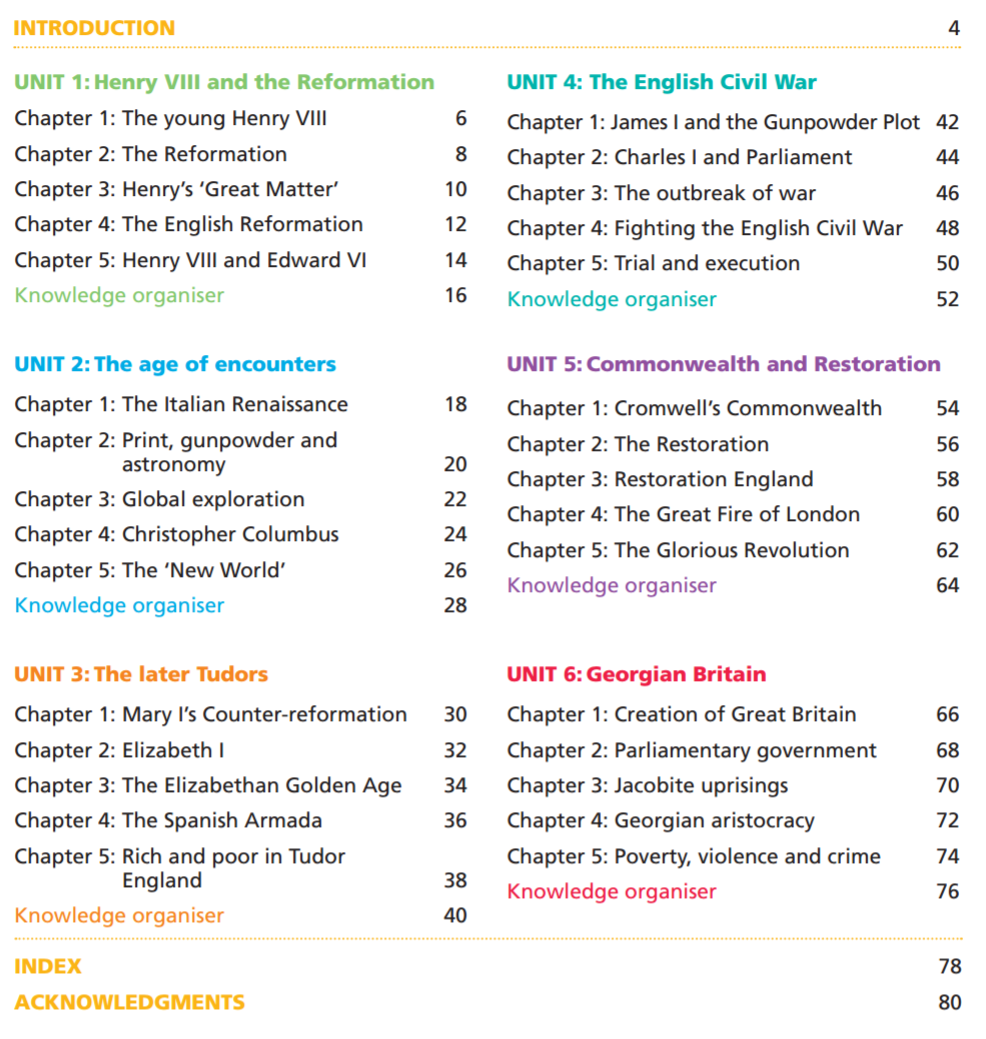

Looking at the broader story, it is clear that Peal has adopted something of the “Grand Narrative” approach to the history of Britain, as you can see below from the chapter titles of the first two books:

The first question I asked of the 'Knowing History' series was how well it developed the core narrative of the book. To do this, I looked at the second book in the series, which covers the period 1509-1760. A sample chapter of this book is available online via Collins.

In terms of the text itself, it is well written and flows naturally within each chapter. The language used is also very ambitious, which is to be applauded. There is no shying away from terms such as “intercession” or “Indulgences”, again something I think more textbooks publishers should promote. Sadly however some terms are left for students to look up in the glossary, rather than having in-text or contextual explanations.

I did experiment with reading the book aloud and found it to be passable. The story jumps around a bit in different sections, but there are certainly chapters which flow extremely well. There are also a range of stories woven into the text. Sadly, many of these seem to be from a very small and exclusive group at the top of society.

Looking at the broader story, it is clear that Peal has adopted something of the “Grand Narrative” approach to the history of Britain, as you can see below from the chapter titles of the first two books:

Despite the good flow within chapters, the overall story feels somewhat stilted. In fact it feel like the book might fall into the trap of “stumbling from reign to reign [calling a halt] at each prince’s death” (Bloch, 1992, p. 146). The Reformation section provides a good example of this. We begin with Henry jousting and making peace with Francis I; diverge into the European Reformation; segue back into Henry VIII’s “great matter” of marriage and child bearing; before 300 or so words note that Henry broke with Rome, ostensibly to get power and remarry. None of this feels like a particularly detailed or cogent understanding of the major issues involved in the English Reformation.

On the plus side, there does appear to be a good coverage of what might be termed the British (English?) 'historical canon'. Yet the first thing which really struck me is that this content list bears a striking similarity with the chapters of Sellar and Yeatman’s 1930 satire '1066 and all that'; the classic history text containing “All the history you can remember”. To take Sellar and Yeatman's section on Henry VIII as a comparison, we find:

Of course it could be said that 'social justice' sits at the heart of the curriculum design as it is so heavily influence by the Hirsch school of thinking; there is a focus on developing of 'cultural capital' from the outset. In the sample chapter from the Early Modern book, pupils are quickly acquainted with the Holy Roman Empire, the Field of the Cloth of Gold, Wolsey and his role as Henry VIII’s adviser, Martin Luther, Alexander VI and so on (although curiously Clement VII only ever appears as ”Clement” for some reason). Important for students to know? Certainly. But the best way for them to develop this knowledge? Debatable.

Are there any narrative oversights?

Another aspect I look for in a textbook series is what stories are not told (or in other words, what I will need to fill in using other resources). I don't have time to do this for the whole series, so I will just look at the Year 7 book. Comparing the 'Knowing History' series to the Year 7 SHP textbook being sold by Hodder, there are many areas of similarity, but also some real differences.

Items missing from SHP book but in Peal: Viking invasion and settlement; Alfred the Great and the Danelaw; The Anglo-Saxon Golden Age; The names of Crusader states (oddly one of the few non-English aspects included); Eleanor of Aquitaine and Isabella of France; The Wars of the Roses

Items missing from Peal's book but in SHP: Life in Iron Age Britain; Life in Roman Britain; Building of Roman Empire; Roman Army and their success; Changes in Britain from Iron Age to Normans; A study of soldiers who fought at Hastings; the cultural impact of the Norman Conquest; Life in medieval towns; The development of armour; The nature of medieval kingship; A study of Edward II and Richard II; Overview of all medieval rulers; Why people liked Robin Hood stories; A study of Shakespeare's interpretation of Agincourt; A detailed look at life in Baghdad; Late medieval exploration, early Renaissance, early medical Renaissance, political Renaissance, Reformation ideas, development of the printing press, The Dissolution of the monasteries; Henry VIII’s rule; A range of enquiries looking at evidence, significance, historical interpretation, and change and continuity.

There are also smaller narrative oversights which are interesting. In the sample section of the Year 8 book for example, I found it strange that, in a book which is ostensibly about England, is that there is no real mention of English reformers whose actions arguably played a much bigger role in the Reformation in England than Calvin or Luther. There is no hint of Wycliffe, the Lollards, Ball, or the like. Why is this so important? Well, because it is key to understand that the Henrician Reformation was not a sudden break but part of a much longer process of agitation for reform. Rather than Henry leading his people into change, it could be argued that he followed them into it. Equally it is important to note that Luther and Calvin had a much greater impact on later dissenting groups, such as the Puritans.

So this begs the question: why is it necessary for students to look at Calvin and Luther at this point in the curriculum? Certainly students are not asked to engage with their ideas, nor are they asked to draw on their knowledge to explore whether the criticisms the reformers made were valid or otherwise. And of course, with the English focus, students are also not asked to explain why there was a Reformation in Europe. Indeed, the Reformation is pinned to a single main event, the nailing of Luther’s theses to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral. I fear that the causation here remains implicit and might fall more comfortably under the heading of what Marc Bloch called “the obsession with origins” (Bloch, 1992, p. 24). However, as Bloch notes, this search for the roots of a phenomenon such as the English Reformation can often lead to ambiguity. In searching for origins are we seeking beginnings, or causes. He goes on to say that “in popular usage, an origin is a beginning which explains. Worse still, a beginning which is a complete explanation. There lies the ambiguity, and there the danger” (Bloch, 1992, p. 25). Here, Calvin and Luther appear both as origins of the English Reformation, and an explanation for it. There is no real critical engagement with the inevitability or otherwise of events which then transpired in England. We have an origin story which explains in totality.

Summary

Thus far we have looked at the importance of unpicking what narrative is provided in any textbook series and whether this contains any oversights. For me there are too many narrative oddities in Peal's book which would need plugging by other resources or teacher expertise. This is why I think it is so important that we ask these basic questions of any textbooks, from Aaron Wilkes to Ben Walsh. In my next blog I intend to focus further on choosing a textbook series by asking questions about the nature of the narratives developed in books. As ever, please feel free to leave comments below or via Twitter.

On the plus side, there does appear to be a good coverage of what might be termed the British (English?) 'historical canon'. Yet the first thing which really struck me is that this content list bears a striking similarity with the chapters of Sellar and Yeatman’s 1930 satire '1066 and all that'; the classic history text containing “All the history you can remember”. To take Sellar and Yeatman's section on Henry VIII as a comparison, we find:

- “Bluff King Hal” (which covers Henry shows off his sporting prowess and removes a few ministers) – not too dissimilar to Peal’s “Young Henry VIII”

- “The Restoration” (ironically titled – it covers Henry’s divorce and break with Rome – very much a “Good Thing”) – Peal: “The Reformation”

- “Henry’s Plan Fails” (in which Henry keeps trying and failing to have a son; giving up in the end to “play Diplomacy” on the “Fields of the Crock of Gold”) – Peal: “Henry’s Great Matter”

- “End of Wolsey” connects brilliantly to the quote Peal chooses for Wolsey’s demise, which Sellar and Yeatman rework as “If I had served my God as I have served my King, I would have been a Good Thing,” before Wolsey expires in the full knowledge he is a “Bad Man”.

- “The Monasteries” (in which Henry decrees the Middle Ages over to the monks who had not realised it) – Peal: “The English Reformation”

Of course it could be said that 'social justice' sits at the heart of the curriculum design as it is so heavily influence by the Hirsch school of thinking; there is a focus on developing of 'cultural capital' from the outset. In the sample chapter from the Early Modern book, pupils are quickly acquainted with the Holy Roman Empire, the Field of the Cloth of Gold, Wolsey and his role as Henry VIII’s adviser, Martin Luther, Alexander VI and so on (although curiously Clement VII only ever appears as ”Clement” for some reason). Important for students to know? Certainly. But the best way for them to develop this knowledge? Debatable.

Are there any narrative oversights?

Another aspect I look for in a textbook series is what stories are not told (or in other words, what I will need to fill in using other resources). I don't have time to do this for the whole series, so I will just look at the Year 7 book. Comparing the 'Knowing History' series to the Year 7 SHP textbook being sold by Hodder, there are many areas of similarity, but also some real differences.

Items missing from SHP book but in Peal: Viking invasion and settlement; Alfred the Great and the Danelaw; The Anglo-Saxon Golden Age; The names of Crusader states (oddly one of the few non-English aspects included); Eleanor of Aquitaine and Isabella of France; The Wars of the Roses

Items missing from Peal's book but in SHP: Life in Iron Age Britain; Life in Roman Britain; Building of Roman Empire; Roman Army and their success; Changes in Britain from Iron Age to Normans; A study of soldiers who fought at Hastings; the cultural impact of the Norman Conquest; Life in medieval towns; The development of armour; The nature of medieval kingship; A study of Edward II and Richard II; Overview of all medieval rulers; Why people liked Robin Hood stories; A study of Shakespeare's interpretation of Agincourt; A detailed look at life in Baghdad; Late medieval exploration, early Renaissance, early medical Renaissance, political Renaissance, Reformation ideas, development of the printing press, The Dissolution of the monasteries; Henry VIII’s rule; A range of enquiries looking at evidence, significance, historical interpretation, and change and continuity.

There are also smaller narrative oversights which are interesting. In the sample section of the Year 8 book for example, I found it strange that, in a book which is ostensibly about England, is that there is no real mention of English reformers whose actions arguably played a much bigger role in the Reformation in England than Calvin or Luther. There is no hint of Wycliffe, the Lollards, Ball, or the like. Why is this so important? Well, because it is key to understand that the Henrician Reformation was not a sudden break but part of a much longer process of agitation for reform. Rather than Henry leading his people into change, it could be argued that he followed them into it. Equally it is important to note that Luther and Calvin had a much greater impact on later dissenting groups, such as the Puritans.

So this begs the question: why is it necessary for students to look at Calvin and Luther at this point in the curriculum? Certainly students are not asked to engage with their ideas, nor are they asked to draw on their knowledge to explore whether the criticisms the reformers made were valid or otherwise. And of course, with the English focus, students are also not asked to explain why there was a Reformation in Europe. Indeed, the Reformation is pinned to a single main event, the nailing of Luther’s theses to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral. I fear that the causation here remains implicit and might fall more comfortably under the heading of what Marc Bloch called “the obsession with origins” (Bloch, 1992, p. 24). However, as Bloch notes, this search for the roots of a phenomenon such as the English Reformation can often lead to ambiguity. In searching for origins are we seeking beginnings, or causes. He goes on to say that “in popular usage, an origin is a beginning which explains. Worse still, a beginning which is a complete explanation. There lies the ambiguity, and there the danger” (Bloch, 1992, p. 25). Here, Calvin and Luther appear both as origins of the English Reformation, and an explanation for it. There is no real critical engagement with the inevitability or otherwise of events which then transpired in England. We have an origin story which explains in totality.

Summary

Thus far we have looked at the importance of unpicking what narrative is provided in any textbook series and whether this contains any oversights. For me there are too many narrative oddities in Peal's book which would need plugging by other resources or teacher expertise. This is why I think it is so important that we ask these basic questions of any textbooks, from Aaron Wilkes to Ben Walsh. In my next blog I intend to focus further on choosing a textbook series by asking questions about the nature of the narratives developed in books. As ever, please feel free to leave comments below or via Twitter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed