Chapter 6: Life after levels

Ah, now we get to the one I have been waiting for. Life after levels has obsessed me since 2011 when I was allowed to start tinkering with the assessment systems in my department. Since then, I have spoken to hundreds of people on this same subject, even more so since the demise of levels in 2014. Yet when I give these talks, I always seem to meet the same resistance: a lack of support from senior leaders; a lack of time; a lack of expertise; a belief that levels work; a slavish adherence at school level to GCSE grades. I am fascinated to see what Christodoulou offers as suggestions therefore and whether these have any impact on the prevailing inertia amongst school leaders up and down the country.

I was pleased to see Christodoulou put so much emphasis on the importance of a progression model and to highlight those same problems of resistance to change. Where I am more sceptical is her belief that the textbook can be a stand-in for a progression model. Whilst I am a big fan of textbooks, I am not sure that they can fully replace a department’s responsibility to consider progression for three main reasons:

Beyond this point, Christodoulou makes some useful observations about the need for a clarity of purpose in a curriculum (though once again it is implied that all should see the same value in education if we are to follow a core curriculum set by a textbook). I was left less convinced however that there were any concrete proposals to work on. Perhaps this is because defining progression needs to happen at a subject-specific level; however I feel a few more links to useful models of progression (which are mentioned) would have been very helpful.

The one model of progression which is explored in more depth is that connected with phonics. The links to Christodoulou’s suggestions are clear, but there are again aspects of control and power dynamics which are conveniently side-lined. When teachers decide which words to teach they are automatically applying judgements to them. When they allow someone else to make those judgments (as in a textbook) they are absolving themselves of responsibility for those choices and potentially reinforcing particular power structures. We may feel we are a long way from this in the liberal idyll of the C21st but this was very common practice in the 1930s and 40s as well as in oppressive regimes today.

Above all, I think much of the work Christodoulou talks about here on progression already exists in the history teaching community. Indeed, there are even whole textbook series published by the SHP dedicated to making these progression models accessible to teachers and helping those same teachers to improve their expertise. Some further exploration of these texts would be particularly helpful for anyone interested in this area I feel.

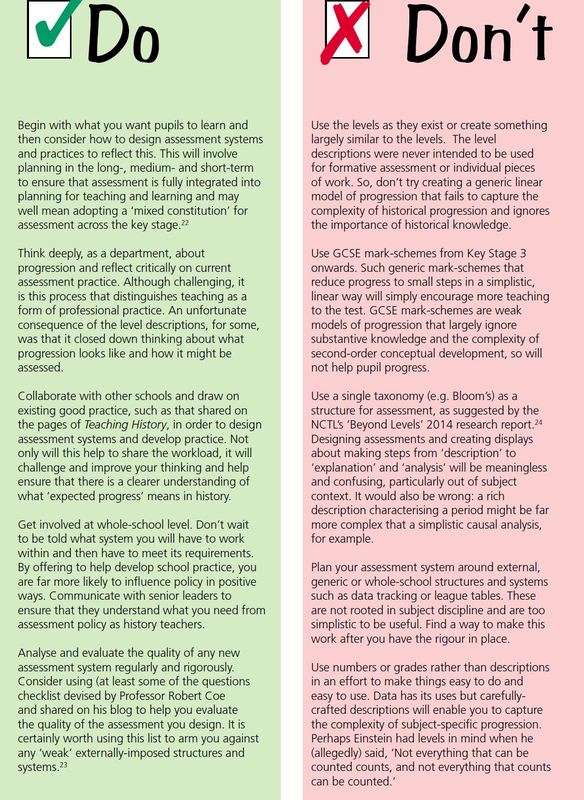

For those wanting a quick summary of Christodoulou’s main thrust here (especially in relation to history) it might be quicker to read Burnham & Brown’s one page “Do and Don’t” summary for life after levels (Teaching History 157, p.17)

Ah, now we get to the one I have been waiting for. Life after levels has obsessed me since 2011 when I was allowed to start tinkering with the assessment systems in my department. Since then, I have spoken to hundreds of people on this same subject, even more so since the demise of levels in 2014. Yet when I give these talks, I always seem to meet the same resistance: a lack of support from senior leaders; a lack of time; a lack of expertise; a belief that levels work; a slavish adherence at school level to GCSE grades. I am fascinated to see what Christodoulou offers as suggestions therefore and whether these have any impact on the prevailing inertia amongst school leaders up and down the country.

I was pleased to see Christodoulou put so much emphasis on the importance of a progression model and to highlight those same problems of resistance to change. Where I am more sceptical is her belief that the textbook can be a stand-in for a progression model. Whilst I am a big fan of textbooks, I am not sure that they can fully replace a department’s responsibility to consider progression for three main reasons:

- Textbooks, when used as progression models, dictate curriculum. It is the professional responsibility of teachers to ensure their curricula meet the needs of the pupils they teach. This might be guided by textbook publishers but it should not be outsourced to them – not least because some have fairly dubious interpretations of events.

- Textbook models of progression are based on subject models of progression. If we want to have excellent teachers, then we need them to engage in what it means to make progress in their subject and not leave this up to authors. A teacher who does not understand progression in their subject is deprofessionalised and unable to understand the activities a book contains.

- Fears of textbooks are not entirely unfounded. These fears are only realised however when textbooks become instruments of state control rather than free choice.

Beyond this point, Christodoulou makes some useful observations about the need for a clarity of purpose in a curriculum (though once again it is implied that all should see the same value in education if we are to follow a core curriculum set by a textbook). I was left less convinced however that there were any concrete proposals to work on. Perhaps this is because defining progression needs to happen at a subject-specific level; however I feel a few more links to useful models of progression (which are mentioned) would have been very helpful.

The one model of progression which is explored in more depth is that connected with phonics. The links to Christodoulou’s suggestions are clear, but there are again aspects of control and power dynamics which are conveniently side-lined. When teachers decide which words to teach they are automatically applying judgements to them. When they allow someone else to make those judgments (as in a textbook) they are absolving themselves of responsibility for those choices and potentially reinforcing particular power structures. We may feel we are a long way from this in the liberal idyll of the C21st but this was very common practice in the 1930s and 40s as well as in oppressive regimes today.

Above all, I think much of the work Christodoulou talks about here on progression already exists in the history teaching community. Indeed, there are even whole textbook series published by the SHP dedicated to making these progression models accessible to teachers and helping those same teachers to improve their expertise. Some further exploration of these texts would be particularly helpful for anyone interested in this area I feel.

For those wanting a quick summary of Christodoulou’s main thrust here (especially in relation to history) it might be quicker to read Burnham & Brown’s one page “Do and Don’t” summary for life after levels (Teaching History 157, p.17)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed