In my current blog series, I am exploring the kinds of questions a history department might want to ask before choosing a set of textbooks. In my first blog I explored the narrative structure of the book, and in my second I looked at how that narrative was conveyed. In this blog I intend to get to a central matter: which aspects of knowledge are developed.

In 2014, Tim Oates released a policy paper entitled ‘Why Textbooks Count’. In this paper, Oates criticised the state of textbook publication in the UK, particularly in light of the perceived failure of books to develop coherent curriculum knowledge. This theme was also picked up by Nick Gibb in his speech to the BESA Conference in 2015. I am not going to go into depth on the merits or demerits of Oates’ and Gibb’s analyses here (although if you are interested, Ed Podesta produced a great series on this HERE) largely because I believe there are some awful things being done in the name of making textbooks ‘accessible’. However, I do not subscribe to the bleak view outlined in Oates’ and Peal’s upcoming talk, that textbooks are dreadful because they are knowledge-light, magazine-like, and demeaning of the past.

In this blog, I intend to directly address the content developed in various textbooks. I am including Peal’s series again here as it is one of the books which came out of Oates’ criticisms of books, and has been put forward as a solution to the problematic textbooks of old; a “renaissance of intellectually demanding and knowledge-rich textbooks in England's schools” as Gibb put it (Gibb in Oates, 2014).

In 2014, Tim Oates released a policy paper entitled ‘Why Textbooks Count’. In this paper, Oates criticised the state of textbook publication in the UK, particularly in light of the perceived failure of books to develop coherent curriculum knowledge. This theme was also picked up by Nick Gibb in his speech to the BESA Conference in 2015. I am not going to go into depth on the merits or demerits of Oates’ and Gibb’s analyses here (although if you are interested, Ed Podesta produced a great series on this HERE) largely because I believe there are some awful things being done in the name of making textbooks ‘accessible’. However, I do not subscribe to the bleak view outlined in Oates’ and Peal’s upcoming talk, that textbooks are dreadful because they are knowledge-light, magazine-like, and demeaning of the past.

In this blog, I intend to directly address the content developed in various textbooks. I am including Peal’s series again here as it is one of the books which came out of Oates’ criticisms of books, and has been put forward as a solution to the problematic textbooks of old; a “renaissance of intellectually demanding and knowledge-rich textbooks in England's schools” as Gibb put it (Gibb in Oates, 2014).

What range and depth of substantive knowledge is developed by my textbooks?

I have chosen to compare three books in the first part of this blog: Peal’s ‘Knowing History, 1066-1509’; Dawson & Wilson’s ‘SHP History Year 7’; and Shepherd et al.’s ‘Contrasts and Connections’. To give a little context ‘Contrasts and Connections’ was released with the advent of the new National Curriculum in 1991, and ‘SHP Year 7’ with the curriculum reforms of 2007 (which placed a focus on thematic history). I will say from the outset that I am not a fan on the thematic structure of the ‘SHP Year 7’ book and generally speaking, I used to teach from this in a different order to the one presented. However, I think it is worth saying that it is hard to teaching a period like the Middle Ages without covering some things thematically, and all three books break from the narrative march to various degrees in order to develop some longer narratives in isolation.

I have chosen to compare three books in the first part of this blog: Peal’s ‘Knowing History, 1066-1509’; Dawson & Wilson’s ‘SHP History Year 7’; and Shepherd et al.’s ‘Contrasts and Connections’. To give a little context ‘Contrasts and Connections’ was released with the advent of the new National Curriculum in 1991, and ‘SHP Year 7’ with the curriculum reforms of 2007 (which placed a focus on thematic history). I will say from the outset that I am not a fan on the thematic structure of the ‘SHP Year 7’ book and generally speaking, I used to teach from this in a different order to the one presented. However, I think it is worth saying that it is hard to teaching a period like the Middle Ages without covering some things thematically, and all three books break from the narrative march to various degrees in order to develop some longer narratives in isolation.

I think it would be remiss of me not to mention that I am not always a fan of the enquiry question approach taken by many SHP books. This is generally because I like to set my own enquiries which suit my choice of curriculum. In this sense, Peal does offer a significant advantage in that his books can be used to tackle multiple questions, a bit like with Ben Walsh's core 'Modern World' books (an issue which I will cover in another blog). Meanwhile many SHP texts are locked down to particular routes or enquiries. A study of the Crusader states is not part of Dawson & Wilson for example. I certainly think this can be an issue, but one which can be solved by not relying on a single book. But if we are going to take the approach Oates suggests, we should be using the textbook as the curriculum. If this is the case, then there should be little need for teachers to go beyond the book (a contentious point but important for this debate).

For the purposes of this section however, I am simply interested in which substantive details are introduced and developed in comparable chapters. I am going to focus on the topic area of peasant life in the Middle Ages (post Conquest), as this is taught in almost all schools I have visited over the last ten years. For me it is also a crucial topic, because one needs to address the mentalities and social structures of medieval life if one is to fully understand key events such as the Black Death, Peasants’ Revolt, Lollardy, and so on. For the purposes of this analysis, I have left aspects of the medieval church and crime and punishment separate and not counted those (largely so that I might finish this project at some point).

How much time is spent on different topics?

First it is worth comparing how many pages (and words) are given over to peasant life.

For the purposes of this section however, I am simply interested in which substantive details are introduced and developed in comparable chapters. I am going to focus on the topic area of peasant life in the Middle Ages (post Conquest), as this is taught in almost all schools I have visited over the last ten years. For me it is also a crucial topic, because one needs to address the mentalities and social structures of medieval life if one is to fully understand key events such as the Black Death, Peasants’ Revolt, Lollardy, and so on. For the purposes of this analysis, I have left aspects of the medieval church and crime and punishment separate and not counted those (largely so that I might finish this project at some point).

How much time is spent on different topics?

First it is worth comparing how many pages (and words) are given over to peasant life.

This of course is just a single aspect which the books look at, and of course needs to be considered in light of the broader content coverage (as outlined in my first blog). That said, I think medieval life probably deserves a good chunk of time given that it represents over 500 years (depending how we are cutting it) of ordinary people’s lives. As far as I can see, Peal’s ‘Medieval Life’ chapter is one of only a handful where ordinary people take centre stage in the book (this is also worth considering, though you may find this an acceptable approach to history).

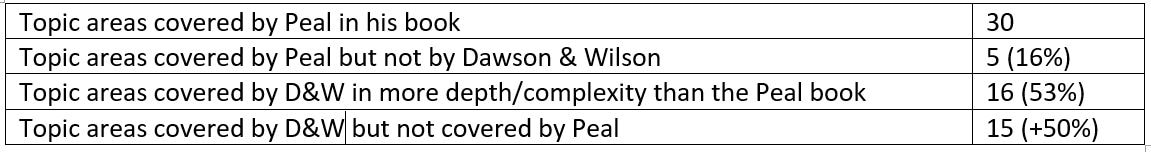

It might be argued that Peal covers other things in his book, whereas Shepherd et al. and Dawson & Wilson spend a long time doing medieval life in depth. To check I was not unfairly ignoring other content developed I did a comparison between the overall content of Dawson & Wilson and Peal. What was notable was the huge amount of overlap between the two, which you can find in full HERE. The table below summarises key areas of similarity and difference.

It might be argued that Peal covers other things in his book, whereas Shepherd et al. and Dawson & Wilson spend a long time doing medieval life in depth. To check I was not unfairly ignoring other content developed I did a comparison between the overall content of Dawson & Wilson and Peal. What was notable was the huge amount of overlap between the two, which you can find in full HERE. The table below summarises key areas of similarity and difference.

Comparing like with like

I have been forced, due to time constraints, to narrow this comparison down to just two books. If anyone would like to contribute others, I am happy to add them.

It would be ridiculous to say that a teacher might cover Dawson & Wilson’s 18 pages in the same time allocation as Peal’s 4, so we need to consider other methods of comparison. Looking at Peal’s accompanying scheme of work, he suggests spending 2 lessons looking at the medieval village. This includes reading pages 30-31 of his book and studying four images from the Luttrell Psalter (not included in the book). As such, I have chosen to make the comparison on what I might cover in 2 lessons on life in the Middle Ages (basing this on my own Year 7 scheme of work from 2011) but sticking to what content is in the SHP Year 7 book. This would effectively be pages 126-7, and pages 134-39 (I generally skip pages 128-133 and would probably spend longer than 2 lessons on this topic, bringing in pages 140-54 as well for added breadth).

I have been forced, due to time constraints, to narrow this comparison down to just two books. If anyone would like to contribute others, I am happy to add them.

It would be ridiculous to say that a teacher might cover Dawson & Wilson’s 18 pages in the same time allocation as Peal’s 4, so we need to consider other methods of comparison. Looking at Peal’s accompanying scheme of work, he suggests spending 2 lessons looking at the medieval village. This includes reading pages 30-31 of his book and studying four images from the Luttrell Psalter (not included in the book). As such, I have chosen to make the comparison on what I might cover in 2 lessons on life in the Middle Ages (basing this on my own Year 7 scheme of work from 2011) but sticking to what content is in the SHP Year 7 book. This would effectively be pages 126-7, and pages 134-39 (I generally skip pages 128-133 and would probably spend longer than 2 lessons on this topic, bringing in pages 140-54 as well for added breadth).

General approach to peasant life

In the Dawson and Wilson book, a series of questions draw together the focus for medieval life: Did people have fun? Were homes uncomfortable? Did farmers have a hard life? Did people try to keep clean? Were towns worth visiting? Was it dangerous to travel? Did people keep clean? Could people help the sick? These questions focus pupils on aspects of similarity and difference as well as change over time between 1100 and 1500.

In the Peal book, the focus is much narrower and falls under the heading: ‘Medieval Life’. It is a little unclear which time period Peal’s chapter is focused on but, as it comes directly after Stephen and Matilda, and includes the suggestion of the Luttrell Psalter, I am assuming the early 14th century.

Comparing substantive knowledge

I have spent a good deal of time comparing the substantive knowledge introduced by both books over the two lesson block described previously. I have coded this knowledge under several key headings as outlined below. My full analysis of this, including specific details, can be found via the link HERE and is open to any corrections.

In the Dawson and Wilson book, a series of questions draw together the focus for medieval life: Did people have fun? Were homes uncomfortable? Did farmers have a hard life? Did people try to keep clean? Were towns worth visiting? Was it dangerous to travel? Did people keep clean? Could people help the sick? These questions focus pupils on aspects of similarity and difference as well as change over time between 1100 and 1500.

In the Peal book, the focus is much narrower and falls under the heading: ‘Medieval Life’. It is a little unclear which time period Peal’s chapter is focused on but, as it comes directly after Stephen and Matilda, and includes the suggestion of the Luttrell Psalter, I am assuming the early 14th century.

Comparing substantive knowledge

I have spent a good deal of time comparing the substantive knowledge introduced by both books over the two lesson block described previously. I have coded this knowledge under several key headings as outlined below. My full analysis of this, including specific details, can be found via the link HERE and is open to any corrections.

As can be seen, in almost all areas, the Dawson & Wilson book introduces a greater range of substantive knowledge than the Peal book in the same time span. The big exception is in terms of taxation. If I were choosing books, I would therefore want to consider which knowledge I considered to be most important, and which I might develop by other means.

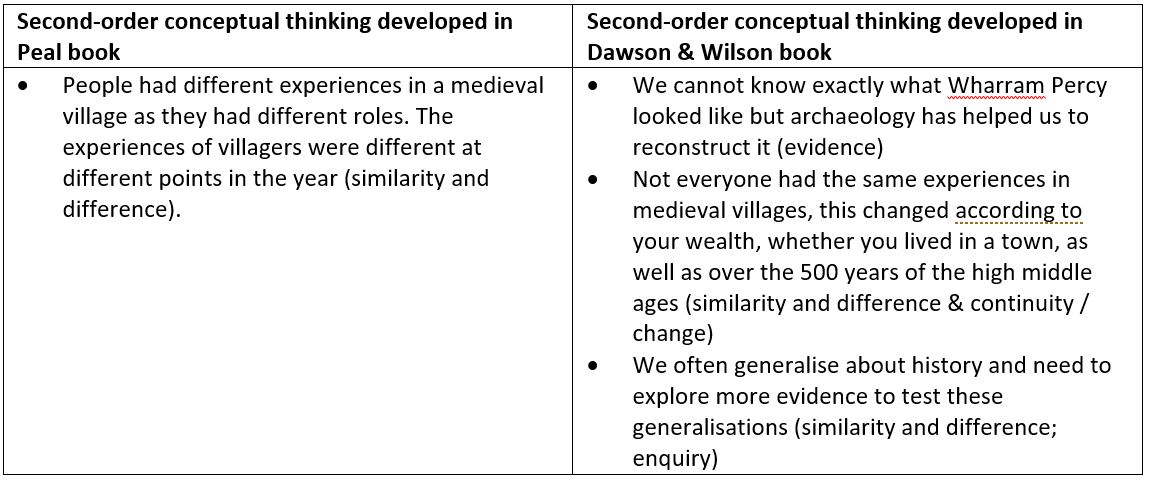

What disciplinary understanding is developed?

Most of this will find its way into a later blog, but one of the hallmarks of good history texts, in my opinion, is that they should also introduce students to the nature of historical study and the kinds of questions which historians raise about the past. Indeed, many commentators have pointed out that good historical narrative will address aspects of second order thinking either overtly, or implicitly. For this comparison therefore I have chosen to unpick the ways in which second-order conceptual thinking have shaped the two textbooks’ respective sections on medieval life.

What disciplinary understanding is developed?

Most of this will find its way into a later blog, but one of the hallmarks of good history texts, in my opinion, is that they should also introduce students to the nature of historical study and the kinds of questions which historians raise about the past. Indeed, many commentators have pointed out that good historical narrative will address aspects of second order thinking either overtly, or implicitly. For this comparison therefore I have chosen to unpick the ways in which second-order conceptual thinking have shaped the two textbooks’ respective sections on medieval life.

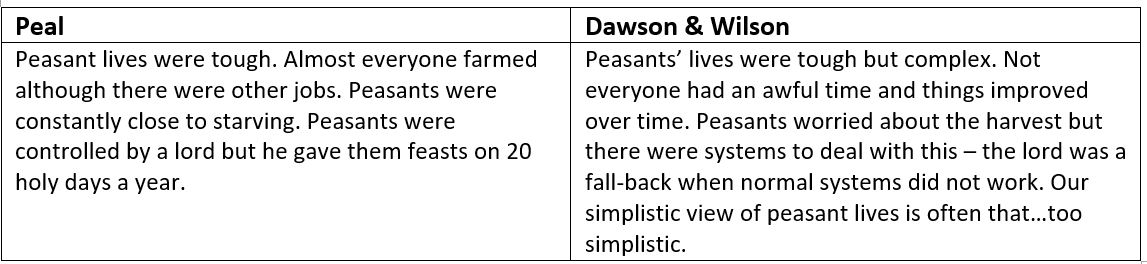

What overall interpretation is given by the section?

Unpicking the individual substantive content is very important when choosing a suitable textbook, however it is always worth stepping back and considering the broader interpretation being communicated in various chapters and sections. This is like a micro-version of the approach I suggested for whole books and series in my second blog. Below I have tried to unpick the overarching narratives of medieval life offered by both books. I think these probably speak for themselves in terms of rigour and complexity.

Unpicking the individual substantive content is very important when choosing a suitable textbook, however it is always worth stepping back and considering the broader interpretation being communicated in various chapters and sections. This is like a micro-version of the approach I suggested for whole books and series in my second blog. Below I have tried to unpick the overarching narratives of medieval life offered by both books. I think these probably speak for themselves in terms of rigour and complexity.

Summary

In this blog, we have explored the importance of asking key questions about the range and depth of knowledge developed by textbooks, as well as their disciplinary rigour and overarching interpretation of aspects of narrative. If you are not convinced by my analysis, please feel free to do your own and share it here, I am happy to add further links.

In my next blog, I will focus on how knowledge is developed and secured through textbook activities and compare this to approaches suggested by cognitive science.

For the rest of the blogs, please follow the link HERE. Comments are always welcome below, or on Twitter @apf102

In this blog, we have explored the importance of asking key questions about the range and depth of knowledge developed by textbooks, as well as their disciplinary rigour and overarching interpretation of aspects of narrative. If you are not convinced by my analysis, please feel free to do your own and share it here, I am happy to add further links.

In my next blog, I will focus on how knowledge is developed and secured through textbook activities and compare this to approaches suggested by cognitive science.

For the rest of the blogs, please follow the link HERE. Comments are always welcome below, or on Twitter @apf102

RSS Feed

RSS Feed