First of all, apologies for the enormous gap between these posts. I have been up to my eyes in school visits and preparations for the final stage of the PGCE. Today’s blog is part 4 of my series exploring how we might go about choosing the most suitable textbooks for our departments. In previous posts, I encouraged people to question the narratives being developed, and the overtness with which the contested nature of the narrative is presented. In my last post, I asked people to consider the range and depth of knowledge presented by a textbook. In this blog, I want to move onto a connected theme and ask how different textbooks help students to develop and deepen their knowledge of the history they study.

To teach from the textbook or not?

Before we begin, I should probably say that I am generally of the opinion that a good history teacher uses a textbook as a tool. They know what they want students to understand and make use of the textbook as a resource to this end, deviating from it where the intended aims are not met by the author. It was a great tragedy that so many teachers during the 1990s and 2000s were told that to even see a textbook in a lesson was a sign of failure. I certainly understand therefore why there has been an enormous backlash against this anti-book culture which seems to pervade in many schools. Of course, I also know why so many people were wary of using textbooks which promoted a very particular kind of history, or which ignored large chunks of the wider world story. Sadly, I don’t have space for more on this debate here, but there are some interesting examples of how this debate has played out internationally too. [i]

In my view, therefore, I tend to check over a textbook for the types of questions and activities it sets, however it is not usually the prime reason I would buy it or otherwise. To take a good example of this, I generally love the ‘Citizens’ Minds’ book by Longman, but I find some of the activities too detailed and time consuming to be practical in a normal history scheme of work. However, many recent voices on the issue of textbook use in schools, have suggested that the textbook should effectively be the progression model for students. This is coupled with the fact that there are large numbers of non-specialists teaching history. Addressing these perceived issues have been part of the drive for the ‘Knowing History’ series released by Robert Peal. Given that Peal is claiming so many other textbooks are “dreadful” at securing progression, it is crucial to consider the types of questions and activities contained within his books, but also those which are being labelled as failing.

What are students asked to recall?

One does not have to look far at the moment to see the influence of neuroscience on mainstream education. Courses are popping up all over the place explaining how we can “make history stick” or promote long term memory in history lessons. It is great to see the profession responding to more recent developments in theory, and I am sure that the new drive for higher quality CPD has had a big influence on this. Such CPD is often based around the work of a few “celebrity” neuroscientists such as Howard-Jones or Willingham.

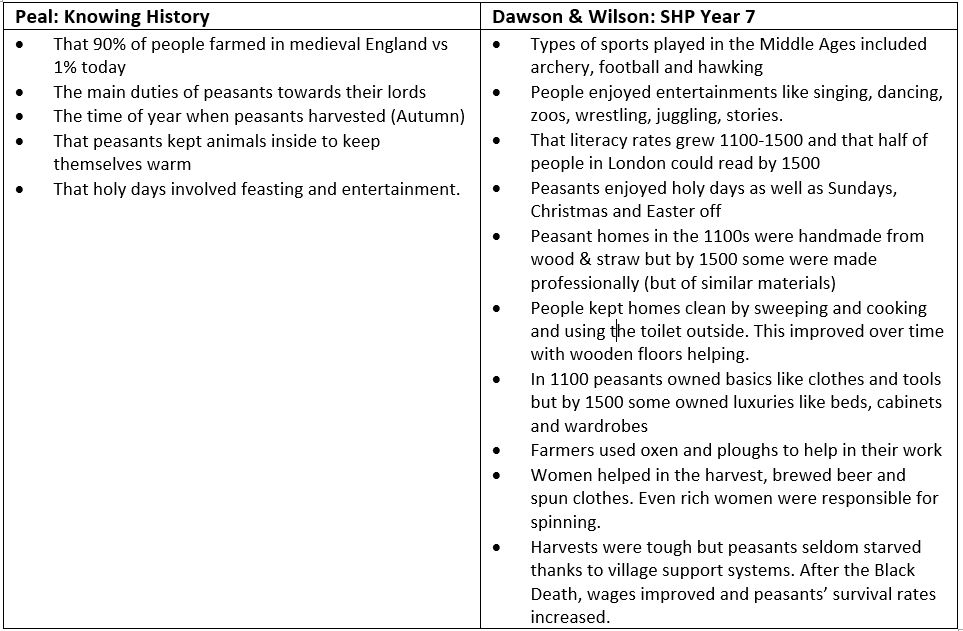

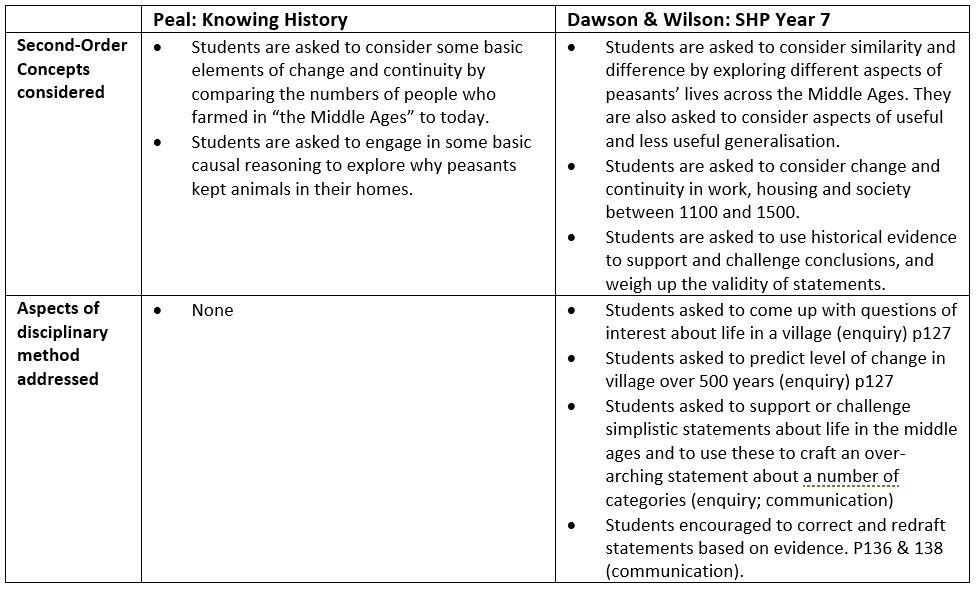

One of the major maxims which has come out of Willingham’s work is that recall and testing are a crucial part of the testing process.[ii] As such, it is worth exploring how often students are asked in textbooks to recall information they have seen in the text they have read. I am going to focus on the medieval life sections I used previously for this comparison, and focus on the knowledge students are asked to recall/extract from the text they have read. The double page spread from ‘Knowing History’ on the medieval village has 5 questions (as with every spread), whilst the sample section I used from the SHP book has around 10 mini-activities which get students to recall/extract in some way. If students were to complete the questions and activities in both books, this is the knowledge they might have recalled in the process:

To teach from the textbook or not?

Before we begin, I should probably say that I am generally of the opinion that a good history teacher uses a textbook as a tool. They know what they want students to understand and make use of the textbook as a resource to this end, deviating from it where the intended aims are not met by the author. It was a great tragedy that so many teachers during the 1990s and 2000s were told that to even see a textbook in a lesson was a sign of failure. I certainly understand therefore why there has been an enormous backlash against this anti-book culture which seems to pervade in many schools. Of course, I also know why so many people were wary of using textbooks which promoted a very particular kind of history, or which ignored large chunks of the wider world story. Sadly, I don’t have space for more on this debate here, but there are some interesting examples of how this debate has played out internationally too. [i]

In my view, therefore, I tend to check over a textbook for the types of questions and activities it sets, however it is not usually the prime reason I would buy it or otherwise. To take a good example of this, I generally love the ‘Citizens’ Minds’ book by Longman, but I find some of the activities too detailed and time consuming to be practical in a normal history scheme of work. However, many recent voices on the issue of textbook use in schools, have suggested that the textbook should effectively be the progression model for students. This is coupled with the fact that there are large numbers of non-specialists teaching history. Addressing these perceived issues have been part of the drive for the ‘Knowing History’ series released by Robert Peal. Given that Peal is claiming so many other textbooks are “dreadful” at securing progression, it is crucial to consider the types of questions and activities contained within his books, but also those which are being labelled as failing.

What are students asked to recall?

One does not have to look far at the moment to see the influence of neuroscience on mainstream education. Courses are popping up all over the place explaining how we can “make history stick” or promote long term memory in history lessons. It is great to see the profession responding to more recent developments in theory, and I am sure that the new drive for higher quality CPD has had a big influence on this. Such CPD is often based around the work of a few “celebrity” neuroscientists such as Howard-Jones or Willingham.

One of the major maxims which has come out of Willingham’s work is that recall and testing are a crucial part of the testing process.[ii] As such, it is worth exploring how often students are asked in textbooks to recall information they have seen in the text they have read. I am going to focus on the medieval life sections I used previously for this comparison, and focus on the knowledge students are asked to recall/extract from the text they have read. The double page spread from ‘Knowing History’ on the medieval village has 5 questions (as with every spread), whilst the sample section I used from the SHP book has around 10 mini-activities which get students to recall/extract in some way. If students were to complete the questions and activities in both books, this is the knowledge they might have recalled in the process:

Even at a summary level, it is clear that the questions in the Dawson and Wilson book ask students to recall more information and on a wider range of topics and issues. Clearly teachers could set additional recall questions, but that is not the point of this comparison.

Does the textbook encourage thinking?

We could argue that it is not the job of a textbook to encourage thinking. However, if any book wants to sell itself on the claim that it helps students to “think critically by focusing on the knowledge they need and checking their understanding” and to “aid pupil memory”, then it should open itself to be tested on this claim. Whilst a good deal of time seems to have been spent on encouraging teachers to get students to recall key information (no bad thing), much less time seems to be spent on Willingham’s central argument that memory is actually the “product of thought”.[iii] In fact, Willingham argues that simple recall hits a wall whereby students can access key facts but do not see the connections between them. He notes that this is often confused as a product of “rote learning” but is in fact a case of “shallow learning”.[iv] This extract from Willingham explains his point perfectly:

Does the textbook encourage thinking?

We could argue that it is not the job of a textbook to encourage thinking. However, if any book wants to sell itself on the claim that it helps students to “think critically by focusing on the knowledge they need and checking their understanding” and to “aid pupil memory”, then it should open itself to be tested on this claim. Whilst a good deal of time seems to have been spent on encouraging teachers to get students to recall key information (no bad thing), much less time seems to be spent on Willingham’s central argument that memory is actually the “product of thought”.[iii] In fact, Willingham argues that simple recall hits a wall whereby students can access key facts but do not see the connections between them. He notes that this is often confused as a product of “rote learning” but is in fact a case of “shallow learning”.[iv] This extract from Willingham explains his point perfectly:

“Cognitive science has shown that what ends up in a learner's memory is not simply the material presented—it is the product of what the learner thought about when he or she encountered the material... When students parrot back a teacher's or the textbook's words, they are, of course, drawing on memory. Thus, the question of why students end up with shallow knowledge is really a question about the workings of memory. Needless to say, determining what ends up in memory and in what form is a complex question, but there is one factor that trumps most others in determining what is remembered: what you think about when you encounter the material. The fact that the material you are dealing with has meaning does not guarantee that the meaning will be remembered. If you think about that meaning, the meaning will reside in memory. If you don't, it won't.”[v]

This is vital because it determines the sorts of questions we might want to ask pupils, or the types of activities we set. If memory is the product of thought then we need to encourage pupils to think more deeply about the content they are attempting to commit to memory (indeed, just the process of thinking will encourage this). If a student is asked to recall the percentage of people who farmed in the Middle Ages, or the main duties of a peasant to their Lord, then they may not even have to engage in thinking about the period or the relevance of these facts at all. In the worst case, a student might simply search for the correct section in the book and copy out the appropriate statement with no understanding at all. Of course, we might argue that amassing such facts is a type of history in its own right, but I tend to agree with Marc Bloch that such historians might better be termed antiquarians, as they have lost their focus on the living, breathing elements of history. [vi] Indeed, Lucien Febrve goes one step further, claiming that such historians are little more than “butterfly collectors”, pinning their lifeless specimens to a board, before placing them behind a glass. [vii]

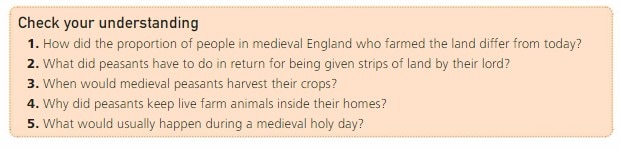

By contrast, the tasks in the Dawson and Wilson book ask students to consider an over-simplified statement about medieval life and then to offer evidence to support or challenge the claim. This in itself requires that students think carefully about the claims being made and think again to test them against evidence. Students are then required to re-write claims to make them more historically valid – a further activity encouraging deeper thinking about the aspects of medieval life which are the focus of the section. The activity is also connected to a relevant question: “Did farmers have a hard life?” again, encouraging students to make connections between the knowledge they extract and its application to an historical question. The neuroscience suggests that activities such as these are more likely to produce durable memories than short recall questions.

Willingham also offers a salient warning about how students might end up with shallow knowledge, arguing that this might come from…

“…students' perception of what they are supposed to learn—and what it means to learn. A student may seek to memorize definitions and pat phrases word-for-word from the book because the student knows that this information is correct and cannot be contested…Students may memorize exactly what the teacher or textbook says in order to be certain that they are correct, and worry less about the extent to which they understand.” [viii]

If we are going to buy textbooks to help students develop their long-term memories and effectively use these to engage with historical questions, then it is critical that we purchase resources which encourage deep thinking about the right things!

Are students encouraged to think about the discipline of history?

Whatever our goals as history teachers, I would imagine that most of us believe that history lessons should put students on the road to understanding the broader discipline of history. How often do we hear the complaint that GCSE is “not proper history”, for example? If students are to become better historians and appreciate what it means to “do history”, then aspects of disciplinary thinking (or second-order concepts, or disciplinary knowledge if you’d rather) need to be at the heart of the thought processes students engage in.

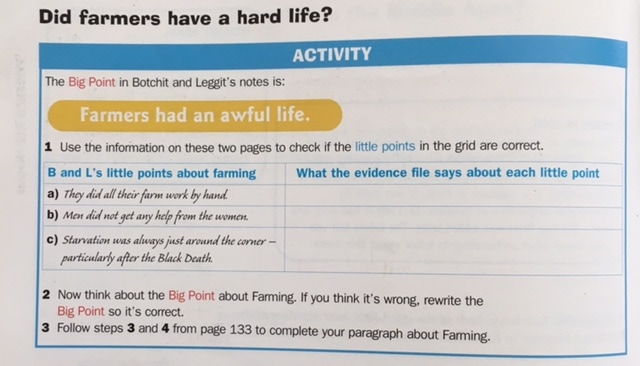

I have gone back to the questions and activities in the ‘Knowing History’ book and ‘SHP Year 7’, however this time I have considered what disciplinary understanding the textbook is trying to develop. For me this is central to maintaining the rigour of our discipline. The results of this one are much starker:

Are students encouraged to think about the discipline of history?

Whatever our goals as history teachers, I would imagine that most of us believe that history lessons should put students on the road to understanding the broader discipline of history. How often do we hear the complaint that GCSE is “not proper history”, for example? If students are to become better historians and appreciate what it means to “do history”, then aspects of disciplinary thinking (or second-order concepts, or disciplinary knowledge if you’d rather) need to be at the heart of the thought processes students engage in.

I have gone back to the questions and activities in the ‘Knowing History’ book and ‘SHP Year 7’, however this time I have considered what disciplinary understanding the textbook is trying to develop. For me this is central to maintaining the rigour of our discipline. The results of this one are much starker:

To go back to Willingham’s points, students working with the Dawson & Wilson book will have been asked to engage much more clearly with what it means to be an historian, and to use disciplinary lenses such as similarity and difference in a more overt and rigorous way. If memory is the product of thought, it is clear which of the two texts will generate a better understanding of the discipline.

Does thinking go beyond text?

The final, connected point is to ask how a textbook makes use of visuals to encourage pupils’ thinking. Whilst text can be effective in many ways, sometimes a picture really does replace a thousand words. The classic example of this for me is the excellent diagrams of Communism and Capitalism from the ‘Modern Minds’ books – a must for anyone introducing these concepts.

Does thinking go beyond text?

The final, connected point is to ask how a textbook makes use of visuals to encourage pupils’ thinking. Whilst text can be effective in many ways, sometimes a picture really does replace a thousand words. The classic example of this for me is the excellent diagrams of Communism and Capitalism from the ‘Modern Minds’ books – a must for anyone introducing these concepts.

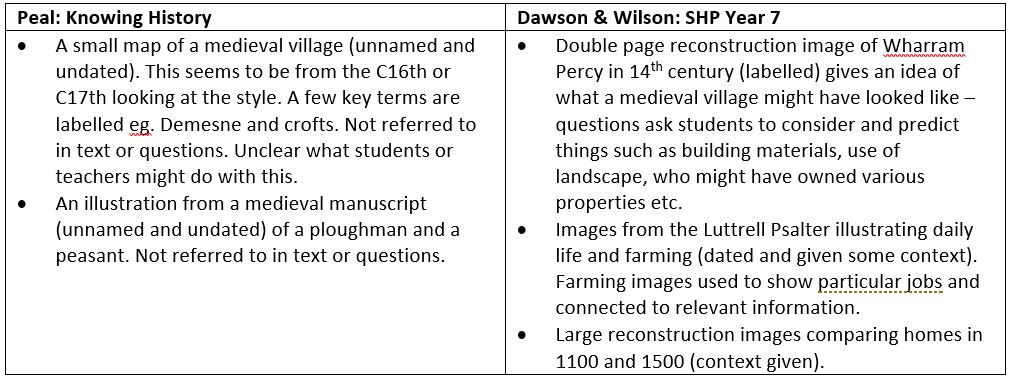

The table below summarises how images and sources are used by the ‘Knowing History’ and ‘SHP Year 7’ books:

The images and sources used in the SHP Year 7 book are utilised to help students puzzle about either the substantive content of history (the Luttrell Psalter and reconstruction images), or the processes of historical enquiry and the broader historical discipline (the image of Wharram Percy). The book guides students to make substantive connections between descriptions of work and the Luttrell images, reinforcing students’ understanding of what bear baiting might have been, or what ploughing involved. These are much more than simple illustrations, they are used to develop thinking. Meanwhile the reconstruction of Wharram Percy asks students to consider how such images are made, and reinforces the idea of history as a process of enquiry. Historical sources and reconstructions are such a central part of understanding the past that I cannot imagine purchasing a book which makes little or no use of them beyond illustration (or visual litter as I once heard it aptly called).

Summary

In this blog, I hope that I have illustrated the importance of considering the tasks set in a textbook and how these encourage thinking about both substantive and disciplinary knowledge. Of course there is more latitude for departments who intend to use books as a resource and not a curriculum, however there are still important questions about supporting teachers, reducing planning load, and having a suitable range of relevant sources and images to support conceptual development.

In my final blog, I intend to look at books in their wider context and ask how they might be used to develop disciplinary understanding as part of a scheme of work.

References

Summary

In this blog, I hope that I have illustrated the importance of considering the tasks set in a textbook and how these encourage thinking about both substantive and disciplinary knowledge. Of course there is more latitude for departments who intend to use books as a resource and not a curriculum, however there are still important questions about supporting teachers, reducing planning load, and having a suitable range of relevant sources and images to support conceptual development.

In my final blog, I intend to look at books in their wider context and ask how they might be used to develop disciplinary understanding as part of a scheme of work.

References

- [i] J. L Granatstein, Who Killed Canadian History? (Toronto: Harper Perennial, 2007); Neeladri Bhattacharya, “Teaching History in Schools: The Politics of Textbooks in India,” History Workshop Journal 67, no. 1 (March 1, 2009): 99–110, doi:10.1093/hwj/dbn050; Keith C. Barton, “History Education and National Identity in Northern Ireland and the United States: Differing Priorities,” Theory into Practice 40, no. 1 (2001): 48–54; Bruce VanSledright, “Narratives of Nation-State, Historical Knowledge, and School History Education,” Review of Research in Education 32, no. 1 (2008): 109–46, doi:10.3102/0091732X07311065; Ken Osborne, “‘Our History Syllabus Has Us Gasping’: History in Canadian Schools B Past, Present, and Future,” Canadian Historical Review 81, no. 3 (September 1, 2000): 403–71, doi:10.3138/chr.81.3.403.

- [ii] Daniel T. Willingham, “What Will Improve a Student’s Memory,” American Educator 32, no. 4 (2008): 17–25; Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger, and Mark A. McDaniel, Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014).

- [iii] Daniel Willingham, “Ask the Cognitive Scientist: Students remember...What They Think about,” American Federation of Teachers, 2003, http://www.aft.org/periodical/american-educator/summer-2003/ask-cognitive-scientist.

- [iv] Ibid.

- [v] Ibid.

- [vi] Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, ed. Peter Burke, trans. Peter Putnam, New Ed edition (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992).

- [vii] George Huppert, “Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch: The Creation of the Annales,” The French Review 55, no. 4 (1982): 510–13.

- [viii] Willingham, “Ask the Cognitive Scientist: Students remember...What They Think about.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed