As academies have the freedom to set their own currciulum and are not bound by the nationally agreed document, the movement of all schools to become academies means an end to over two decades of government-set curriculum. "Good!" you may cry. But actually I am not sure it is all that good. Like it or not, the National Curriculum has done an awful lot of good to British education, as well as the more widely publicised negative impacts. The reason it does some good is mainly down to the fact that it balances out other pressures which the government puts on educations, notably the drive to produce ever improving exam results (but not have more people passing).

You may remember that between 2010 and 2014 there was an enourmous fuss made as Michael Gove and the education people (or otherise - you decide) in Whitehall attempted to re-work and re-write the various statutory frameworks for study. History of course was famously controversial, with a list of content which initial looked like it had been dreamed up by a drunken Nigel Farage on a bender at the Premier Inn with David Starkey and Nial Ferguson. Yet the thing which was always striking about these reforms, was that the academies Gove created did not have to follow this curriculum at all. Why then go to all that trouble if some schools could just ignore the results? Indeed, some schools who became academies were also some of the worst for teaching a narrow, C20th heavy history curriculum. With academy status they had no need to change. Indeed, they were even permitted to continue using National Curriculum Levels if they so chose (and many did!). But at the moment, this is intertia, already there are some major and worrying changes to the curriculua of academies which are setting a potential future trend for English education. The National Curriculum was far from perfect, but it did (and currently does) enshrines a number of principles which may risk being lost if academies continue to be allowed to plough their own curricular furrows. For the purposes of brevity I just want to deal with two of these.

The National Curriculum opens (and historically has opened also) with a key phrase: "Every state-funded school must offer a curriculum which is balanced and broadly based" (DfE, 2014, p. 4). At the heart of the document is a basic entitlement for ALL pupils to receive an education which goes beyond what is measured in national tests, or PISA charts, and gives them real access to a range of experiences in a wider range of subjects. In a world where there is increasing pressure for schools to acheive their 5 A*-C grades including English and Maths, and where English and Maths are double weighted, the National Curriculum protects the rights of pupils in many state schools to access art, design, drama, history, geography and so on. This is absolutely crucial.

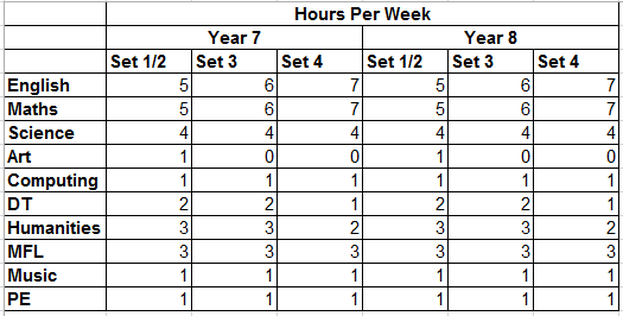

If schools have the responsibility to provide "breadth and balance" removed, what might the result be? It doesn't take much searching to find the answer. There are already secondary schools which run 2 year Key Stage 3 programmes of study, or which push their pupils to take additional English and Maths classes to prepare them for GCSE early. What will the status of Key Stage 3 history be in a school where results are under 50% A*-C? The likely answer is that its status will be significantly reduced or the subject will be removed. If you look at the image above you can see the plan of a Key Stage 3 curriculum in one academy. In this example, students are clearly being streamed. Those at the bottom get less entitlements to humanities from the outset (and none to art!!). So, as it's budget day, let's do the maths. Studdents in sets 1-3 in this school get an entitlement to 234 hours of humanities over their entire Key Stage 3 programme of study. Because they choose options at the end of year 8, this is spread over 2 years, rather than 3. Assuming that Humanities includes history, geography and RE that means 78 hours of KS3 history teaching. Compare that to the 214 hours of history which some schools allocate for study of history alone between years 7 and 9 and you get an idea of the difficulties which are likely to arise. Indeed, the Historical Association's annual survey of secondary schools in England found in 2014 that in 23% of schools, Key Stage 3 history was already being taught in 2 years instead of 3 (Historical Association, 2014).

We have already seen this play out to some extent in the early 2000s with the advent of the integrated humanities approach to foundation subjects. Because curriculum content was significantly lightened and the focus placed on "skills", many schools opted to merge their humanities subjects and reduce their overall curriculum time. The English Baccalaureate award currently gives history a little more status than in the early 2000s, but not in schools where the award is already considered "out of reach" of its pupils. Again, the Historical Association's annual survey found in 2014 that in 44% of schools, children unlikely to get a Grade C at GCSE were being steered away from choosing history as an option.

The National Curriculum was to some extent able to hold the pressure of exam results in a kind of creative tension - forcing schools to keep their borad and balanced provision up until the age of 14. Although, as has been seen, the removeal of testing at the end of Key Stage 3 and the complete removal of National Curriculum levels (as flawed as they were) has allowed the erosion of Key Stage 3 proivsion in many schools and a whittling down to a 2 year course, the basic provision is still there. Unless the DfE introduces some measures to ensure the breadth and balance of school curricula up to Key Stage 4, there is little chance that a borad and balanced entitlement will be maintained accross the country.

The exam issue

One of the biggest threats to the breath and balance of the curriculum has been the increased focus on GCSE results, particualrly in English and Maths. In the HA Survey, 2014, 50% of respondents said that GCSE specifications going to have a major impact on the history being taught at Key Stage 3. With this in mind, the basic content demands of the National Curriculum provide another stay on curriculum narrowing. When the National Curriculum revisions of 2007 removed any real necessity to cover a broad range of historical periods, there was an notable trend for schools to narrow their teaching to cover large amounts of C20th history and little from before. For all its faults, the 2014 curriculum has forced schools to focus on the history of Britain from the Middle Ages to present day and therefore provide a much broader and more balanced view of chronology (although notably not in terms of international perspectives, but that's another issue).

Another key factor is the influence of GCSE examination on progression models for history in schools. The removal of a National Curriculum entitlement could open the floodgates to assessing pupils against GCSE assessment objectives from the beginning of their school career, despite the recent report from the Comission for Assessment Without Levels suggesting this would be a disaster. There are already a number of schools taking such an approach: Pupils arrive at school in Year 7 and are aseessed against GCSE grades 1-9, beginning at the bottom and theoretically rising as they go through. I have written at great length about why this is nonsense, but it is made worse by the removal of a mandatory curriculum entitlement for Key Stage 3. The absence of a proper curriculum to measure progress against risks a complete genericisation and hollowing out of history teaching. Michael Fordham has written about all of the above at some length in an excellent blog HERE. Solutions to this could still give schools a lot of scopeto choose their curriculum, but they must also surely provide a minimum standard for a KS3 curriculum to meet?

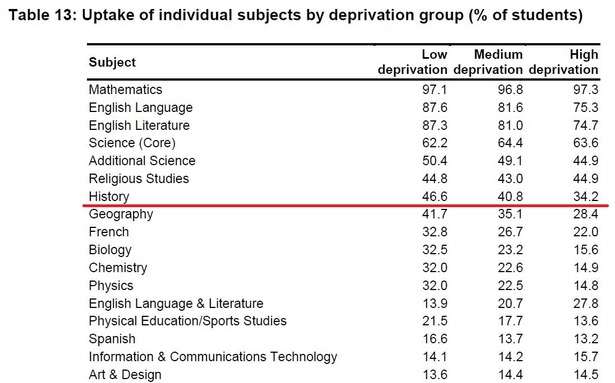

Taken from Tim Gill's report into GCSE subject uptake in 2014 for OCR

Taken from Tim Gill's report into GCSE subject uptake in 2014 for OCR Just as important as considering the potential impact of the loss of the National Curriculum on the pupil population as a whole, is the thought which must be given to its impact on particular groups. Here I want to consider just two, but there are ramifications for all sorts of different groups of pupils.

Girls

For those who have only been teaching since the introduction of the National Curriculum, it seems bizarre to consider a time when boys and girls would not have had the same educational provision. Much post-war education focused on preparing women for the roles they were to fulfill outside of the school environment. Even at a grammar school, my own mother in the 1960s was not encouraged to take more than 2 A Levels, despite the fact that the entrance requirements for girls were placed higher than those for boys (Maynard, 2002). Schools did respond to the changing attitudes of the time, but as ever, this was fairly slow. The Sex Discrimination Act, 1975 prevented schools from forcing girls to take particualr subjects, however the ingrained socialisation of subject selection still determined many girls' choices, and therefore outcomes. It is notable that even today, subjects which are not mandatory on the national curriculum, such as Health and Social Care, or Construction, still top the tables for gender imbalances at GCSE (according to JCQ). Meanwhile subjects which are mandatory on the National Curriculum, such as history, science, geography, or even ICT see a much closer gender balance.

The National Curriculum has been key in ensuring that both girls and boys have equal access to core experiences in school. Whilst it has not been perfect, it is notable that girls' achievement increased around the same time and that girls beliefs about the typoe of work they might do after school have also broadened (Shapre, 2004). Cohen (1998) has noted that girls' performance was traditionally high, but before the 1980s it tended to be in subjects which were valued less by society. The National Curriculum has therefore allowed girls to excel in areas which are seen as important (whether we agree with this categorisation or not).

Pupils from low SES backgrounds

The National Curriculum has also been key for pupils whose socio-economic status might be ranked in the bottom quartile nationally. Just as with girls (above), the National Curriculum has acted to prevent schools from simply preparing such students, as was common before the 1970s, for life as labourers or in low-paid service industries. The class-bias of the UK education system is far too much to deal with here, however, the National Curriculum made it a right for every pupil in the UK to learn history. In 1950, a mere 79,697 pupils took the school certificate in history, and just 80% of schools offered this opportunity. In 2010, 198,800 pupils sat a GCSE history exam and every child in the country received a history education to the age of 14. (Cannadine et al., 2011). Although history was already growing in popularity in secondary modern schools by the 1980s, there were still those which did not pursue the subject because it was felt to be too complex, or irrelevant for pupils. The National Curriculum gave each and every one of these pupils the right to be taught history regardless of the class biases of their teachers. When options are introduced, it is clear to see from the GCSE uptake chart above, that low SES students are less likely to take history.

Coupled with this is the fact that pupils from low SES backgrounds tend also to be those who get the worst overall results in the country. Low SES pupils are a group for whom the term "intervention" probably seems like a way of life at times. At the moment schools already take pupils out of lessons and keep them after school for catch-up and revision, particularly in English and Maths. What then the impact when curriculum provision in Key Stage 3 is allowed to slide? Will these pupils spend their time shuffling from one English intervention class to another, instead of being allowed to have access to the full curriculum. Already we have systems where schools play fast and loose with curriculum by streaming pupils as soon as they arrive. Where do the non-specialist historians get put? In the bottom sets. Where do we teach some historical "fun" instead of developing historical understadning and breadth? In the bottom sets. Which groups of children are actively discouraged from taking history at GCSE?.... and so on. Whatever the justification for such an approach, I cannot see how this can be positive for young people, whose exposure to a breadth of educational expererience should be an absolute priority.

A wailing and a gnashing of teeth

There are of course a whole raft of other important reasons why the removal of the National Curriculum may be a worry for the English education system (and equally a few positives I think). However I worry that because of its general unpopularity, many of us will not be mourning the loss of the National Curriculum as we might. This is precisely why I think we need to go back and consider the other things which a National Curriculum provides us with, and other reasons why its removal, as a minimum basic entitlement, might be problematic.

If, as we are being told, the removal of the National Curriculum and the shift to academies, puts power into the hands of schools, the three big questions we need to ask are:

1) Into whose hands preciseley is that power going?

2) What are they likely to do with that power?

3) To whom are these people accountable?

Even a brief consideration of the potential answers to these questions fills me with a sense of dread! Now is the time for us as teachers to be demanding clarity on what will replace the minimum entitlements enshrined in the National Curriculum if all schools are to become academies. More importantly, to demand how schools will be held accountable to the people they serve for the curriculum they provide. I fear we are already on the fringes of the darkness, but we must be sure that we are not cast out to a place where our sorrows won't be heard.

The National Curriculum is a that odd kind of friend you sometimes find you have. You are never quite sure if you like them, even though they speak some sense. They often feel a bit detached from you, and then at other times are completely overbearing. On occasion you they will do things that make you really mad. But every so often you get a little glimpse at the fact that they are looking out for you too. Then one day they will do something that shows they are really good at heart for all their flaws, and you like them all over again. Sometimes, in a world like this, we need friends like that.

References

Cannadine, Keating & Sheldon (2011) The Right Kind of History, Palgrave Macmillan

Cohen (1998) "A Habit of Healthy Idleness: Boys' Underacheivement in Historical Perspective" in Epsitein, Elwood, Hey & Maw [eds] Failing Boys? Issues in Gender and Achievement, Open University Press

Maynard (2002) Boys and Literacy: Exploring the Issues, RoutledgeFalmer

Maynard (2007) The RoutledgeFalmer Reader in Inclusive Education, RoutledgeFalmer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed