Summer is a great time to review T&L policies for next year. Good way to reflect strategic priorities. Really like these #ukedchat #SLTchat pic.twitter.com/AOv7t2qZ2q

— Alex Ford (@apf102) June 26, 2017

|

This is just a short blog on the back of discussions I had yesterday evening about Teaching and Learning policies in secondary schools. I posted out some extracts from T&L policies from a couple of different schools, which (in my view): manage to place students at the heart of the teaching experience; set out broad principles for why teaching is important; promote wider aspects of good teaching; and are not overly prescriptive in terms of pedagogy.

The reaction to this post was very interesting. On the one hand, the examples got a handful of "likes" but there was quite a lot of criticism too:

2 Comments

I have read many pieces over the years about how gaming might be used as a pedagogical tool in teaching. Today, I want to turn this on its head. I think new teachers can use gaming, or rather the principles behind gaming, as a mirror to reveal some aspects of effective teaching.

Let me explain a bit further. All games, at some level, have to teach their players how to play and be successful in the game world. Once upon a time, this was done with weighty manuals (Civilization 2 had a manual spanning 200 pages when I got that in 1996), but now the teaching aspects of games tend to be embedded in the gameplay. Although games are only ever going to be a proxy for classroom teaching, I do think there are some essential principles followed by the best games, which make their ‘teaching’ elements effective. I call these the “Nintendo Principles”, after the company who, according to Metacritic, have made 5 of the top 10 games of the last 20 years. These ‘Nintendo Principles’ are perfectly illustrated in the most recent release from the Japanese game studio, the Legend of Zelda, Breath of the Wild. The game follows an ‘open world’ approach, meaning that players are thrown in with very little preamble, and can pursue their own path through the game. So far, so progressive. In all honesty, I am not recommending an ‘open world’ approach to teaching, curriculum is too important, but because of its structure, the Legend of Zelda has to do almost all of its ‘teaching’ in game, whilst ensuring there is a good balance of challenge and reward. My contention is that these ‘Nintendo Principles’ are comparable to the fundamentals of good classroom teaching and provide a useful starting point for new teachers to consider their practice. They are also principles which pupils will be aware of, either implicitly or explicitly. Principle 1: Challenge is Important to Motivation Video games producers have a direct interest in ensuring their games hit the right level of challenge. For producers, getting this spot on means more interest, greater longevity, and the prospect of better reviews and critical acclaim. In most adventure games, challenge is linked to story progression (another powerful tool), but it might also be connected to collecting a range of items, achieving certain goals in a number of areas etc. In my last blog, I spent some time explaining why I think we still have a long way to go in teaching students how to engage fully with historical interpretations, and not simply dismissing views on the grounds of an historian’s motive. Today I want to deal with a second key aspect of helping children to become better critical readers both in history, and more broadly, namely historical truth.

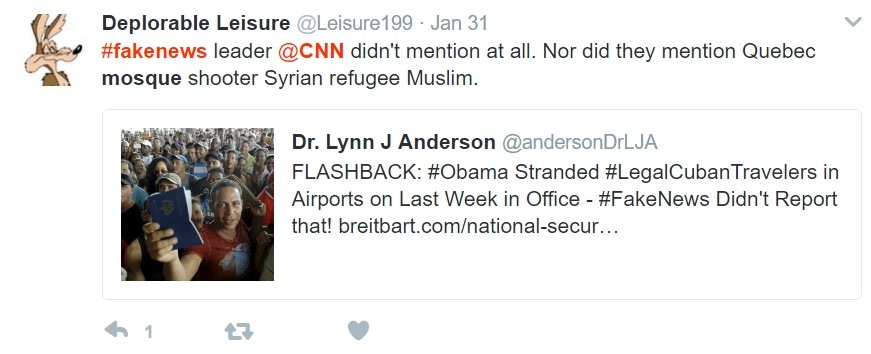

Putting truth back into history I fear we spend too little time talking about historical truth in schools. This is because the idea of historical truth has become immensely unpopular. Post-modernists like Jenkins have argued that history has no objective truth, and that to pretend otherwise is a dangerous fallacy. Indeed, Jenkins (1991, 1995, 1999, 2003, 2009) suggests that all history writing is a battle for different groups to construct their own histories in their own self-interest. Taking this to its extreme, he even made the case for the removal of the study of history altogether (Jenkins, 1999, 2009). To my mind, this rejection of the possibility of historical truth is a dangerous stance to take, now more than ever, and one which prevents our students from being properly critical of different truth-claims. On Friday, the defence secretary. Michael Fallon said that NATO needed to do more to tackle the “false reality” being propagated by Russia. He argued that Russia’s production of “Fake News” was destabilising western democracy and undermining electoral processes. Claims like these are nothing new. For the last six months, the US has been awash with claims of “Fake News” being put out by both the Republicans and Democrats, and a simple search for the #FakeNews hashtag reveals some terrifying results. I find it striking that a country which was born of the declaration that some truths are self-evident, should find itself at the forefront of a post-truth version of politics. All of this is very disturbing, not least because if we are in a post-truth world, there is a very real question about whether knowledge is important any more (I would argue that it is more so than ever - more on this soon). Naturally there has been much soul searching and even more hand wringing about how we approach the issue of truth having been downgraded in our political discourse. In some cases, people are drawing historical parallels and suggesting that we learn the warnings of the 1930s; to be on guard against malicious propaganda; to disbelieve the information coming out of the (insert the group you disagree with here) camp; and so on. History lessons and the post-truth discourse

Followers of the Schools History Project will know that one of the founding principles of the movement was to help students see the relevance of history to their lives, and give them some of the tools to help understand it (Schools History Project, n.d.). Over the last few months, I have seen numerous exhortations in the history teaching community for educators to warn pupils of the dangers of misinformation, and encourage them to be on guard against malign interpretations. Although well intentioned, I think this use of history misses the point of our discipline somewhat. In fact, I wonder if such an approach, namely using history to make pupils sceptical of information, has actually contributed to the post-truth problem. "Do not ye deem, that I came to send peace into earth, I came not to send peace, but sword. For I came to part a man against his father, and the daughter against her mother, and the son's wife against the husband's mother" [Matthew 10: 34-35] NOTE: I have updated this blog in light of some of the comments below. Items in bold are updates.

I have found myself pondering more and more on these verses from Matthew over recent months. To all intents and purposes, I feel like the world around me has become one of stark binaries. Friend or foe? Believer or unbeliever? Leave or remain? Corbynite or a Blairite? Pro-grammar or pro-comprehensive? Neo-trad or progressive? Child-centred or discipline focused? The list goes on and the arguments are endless and largely fruitless. It turns out that I am not the only one to have noticed this. As I was writing this blog, Ed Podesta posted an excellent piece on the same issue. I fear this will be much less eloquent, however I would like to add my own thoughts as one of the people who finds these sharp divisions both troubling and counter-productive. This blog was prompted by two recent events. In the first instance, I posted a letter sent to a friend’s Finnish parents. The letter demanded they leave these shores and stop “polluting the air”. Within seconds, my timeline was filled with tweets acclaiming or decrying such actions. Those on the left of the debate were soon demanding various forms of corporal punishment for the offender and implying that all Leave voters shared such sentiments. Meanwhile, those on the right called me a liar and demanded I prove the verity of the letter, or dismissed it as irrelevant. I took the post down. So today's post is not really a focus on awesome 90s dance music, but it is a follow-up to Rich Kennett's excellent blog on preparing a scheme of work for the new A Levels using enquiry questions. This is a process which I have been engaged in now for a few months. What strikes me is how much I have had to think about how I want to structure the course, even though it is largely (but not entirely) similar to our current A Level. What I have decided is that planning for developing knowledge is, as the Urban Cookie Collective would (probably) say, both the key and the secret to planning a great A Level course.

To give you some context. We currently teach AQA's AS unit on Russia 1855-1917. This feeds into an A2 on the USSR 1941-1991. Under the A Level changes we have opted to go for the new unit which covers 1855-1964 (splitting at 1917 for the purposes of AS examination). On the surface this seemed like the obvious choice and the specification document seemed to bear this out - covering areas we were already comfortable with teaching. However it didn't take too long before we started encountering issues in planning the AS portion of the unit.

So I have been reading "Make it Stick" by Baron, Roediger and McDaniel over the last few days, and I have to say that it has been quite enlightening. The book sets out to explore the neuroscience behind how we learn, setting out the processes involved in learning in an accessible way and making reference to a number of studies. The book does not claim to have complete knowledge of the subject and notes where more research is needed, however I feel it has offered some very useful guidance on how I could move my students on. Most importantly the book deals with a number of myths which are peddled in education especially and debunks these once and for all (VAK I am looking at you).

I was pointed in the direction of the book by Christine Counsell and Michael Fordham. Michael in particular has posted three excellent blogs on the specific application of the book to issues of planning in history. (Blog 1, Blog 2, Blog 3). However, I wanted to focus more specifically on helping students to grasp some of the key points from the book. As such, I attach a PowerPoint which could be looked at in one, two or three sessions. I would suggest it will work best with KS4 or 5 and, in the spirit of creating a sense of urgency, should be linked to the idea that mastering memory is key to exam success.

OK, so I am not even going to make the pretense of being brief here! The attached document (below) outlines my current thinking about how we might make assessment work in a whole school context. As suggested by the title, this has been something of an epic struggle and I am pretty sure I haven't got it right, however I hope that it might at least spark some discussion.

I would like to make mention again however of the excellent work being done by Michael Fordham at http://clioetcetera.wordpress.com/ on this issue which has been crucial in forming many of my ideas. As ever, all thoughts and comments are appreciated! So we have spent quite a long time over the last nine months considering how we might develop a system of progression and assessment suitable for a post levels world. We have made many revisions along the way, however I think we now have something which we are reasonably happy with. To give a brief outline we:

The "Teaching MOT" - the ticket to a smooth running profession or just another way to be fleeced?1/11/2014 So the latest furore which has erupted in the world of teaching is a suggestion by the Shadow Education Secretary, Tristram Hunt, that teachers should be licensed in order to stay in the profession, and that a Royal College of Teaching be set up. In an interview with the BBC Hunt noted that teacher should have "the same professional standing" as lawyers and doctors, "which means re-licensing themselves, which means continued professional development, which means being the best possible they can be," (Of course, if Hunt is serious about giving teaching "the same professional standing" as law and medicine, he might want to consider the pay and conditions of teaching as well as the licensing aspect!). He went on to say that "if you're not willing to engage in re-licensing to update your skills then you really shouldn't be in the classroom," Twitter seems to have exploded with anger at the proposals: @sharpeleven: I think @TristramHuntMP may have lost #Labour hundreds of thousands of votes with his idiotic bash-teachers grandstanding. #NoToLabour  The AndAllThat.co.uk teacher blog is moving from WordPress onto the main website. From now on you will find non-topic related content here. You can still access the archives from the WordPress site by visiting http://andallthatweb.wordpress.com . I will endeavour to transfer the content over the next few months. Mr F  A quite brilliant (if post-modern) take on the study of history in schools. I attach both the 1999 original and a 2010 re-vamp. As the arguments over the national curriculum rage on Sam Wineburg’s question over why we should study history at all comes back to mind. Year 13 this is well worth a read (especially as he makes references to Richard White) in terms of historiography and what historical understanding actually means. Wineburg takes the position that we can never fully understand the past, but that does not equate to meaning we should not study history. He goes on to argue that we must try and appreciate our limitations in ever understanding the past. Two bits stand out: Wineburg asks us to consider that we will never appreciate historical context ie. Did the Egyptians see as we do but draw in a different or primitive manner or did the Egyptians simply see differently to us? Importantly can we learn anything from asking this question? Secondly Wineburg notes that the good historian engages with the past through humility, knowledge of ignorance and with heart. What lessons might there be here for school history? Can you see any of Wineburg’s concepts working in the history classroom? How might you have tackled re-writing that textbook? Do you agree with his conclusions on the place of history? And importantly, what relevance does this have in light of curriculum reforms? Or rather, does it matter if it has relevance or not? Comments welcome… Need a brain break now!! Mr F Unnatural and Essential – This article can be downloaded from the HA here: LINK Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts can be viewed with a JStor free account here: LINK Am not sure why I have felt the need to vent about this today. I suppose I am feeling generally frustrated by the resurrection of the skills vs knowledge debate which, as far as I am concerned, was buried decades ago. Of course, the “skills brigade” raise good issues about community engagement, independence and resilience. But surely all teachers believe that these can be developed alongside engaging subject knowledge …where are all these teachers who still throw chalk at children for failing to recite the bible? Never the less, there seems to be good money in telling teachers that they are forcing a Victorian education system on a group of disengaged, working class kids who need reengaging through group work and technology. I am also deeply offended that any challenge to the skills based, “innovative” approaches is said to be an elitist response… As I see it, there are a number of major issues with the approach outlined above.

Schools are increasingly expected to reduce inequality in society in the face of increasing economic divisions. We are told that we must engage a generation of students who have become disengaged from a Victorian education system. This language is being peddled by the Innovation Unit amongst others. There is a worrying trend to see technologies as a solution to “self education” We need to recognise that schools alone cannot close this socio-economic divide, it is a matter for the whole of society but needs direct action from government. However recognising this does not mean accepting the status quo and being happy…far from it, it demands more radical change. Reducing education to a purely “skills-based” curriculum in an attempt to prepare students for a global job market is completely misguided. It is a blunt tool to enact social change and to engage students in the wrong ways. Whilst state schools reduce their subject specialisms to give their students “transferable skills for the economy”, private, public and independent schools continue to offer their students a rich curriculum diet and access to the best jobs and universities. The economic divide remains. The only way in which the socio-economic divide can be overcome is through a society-wide reformation of the neo-liberal precepts on which our society is based. Using schools to do this is attempting to plaster over the ever widening cracks. Our priority should be in supporting those most in need and creating a society which is more equitable. Of course, this will be unpopular amongst the most powerful, and potentially very expensive. We must preserve the idea that education should be available for all children and adults to develop their human potential – it is not about trying to battle market forces. This is not the same as an elitist agenda. A key part of any schooling is democratic education. If we want to add value to students lives, let us first think carefully about what values we want to add. We must recognise that in many cases, taking away subject expertise from education under the guise of equality is a cynical cost cutting exercise. Taking away this expertise is cheating our poorest students out of the chance of engaging in immersive subject experiences. It limits any true passion in learning. To pretend that this is in their best interests is unforgivable. It is not subject irrelevance which leads to children becoming demotivated in their studies, it is the slow realisation that their life is most likely mapped out for them thanks to their upbringing. In many cases the barriers to education just become more extreme as children get older. Subjects only regain their relevance when these barriers are removed. When this is the case, students will be able to study subjects for their own sake and in doing so will engage in the humanising processes of education. This is the real challenge of the C21st. /rant over

|

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed