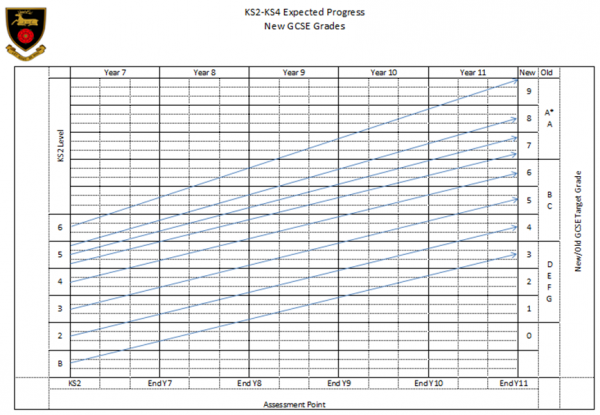

In this blog I want to take a look at how these grade descriptors can be utilised from Years 7-11 to provide a clear and coherent flight path for pupils in history.

Using the grade descriptors to create a flight path

Many schools for instance have opted for the following basic flight path:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed