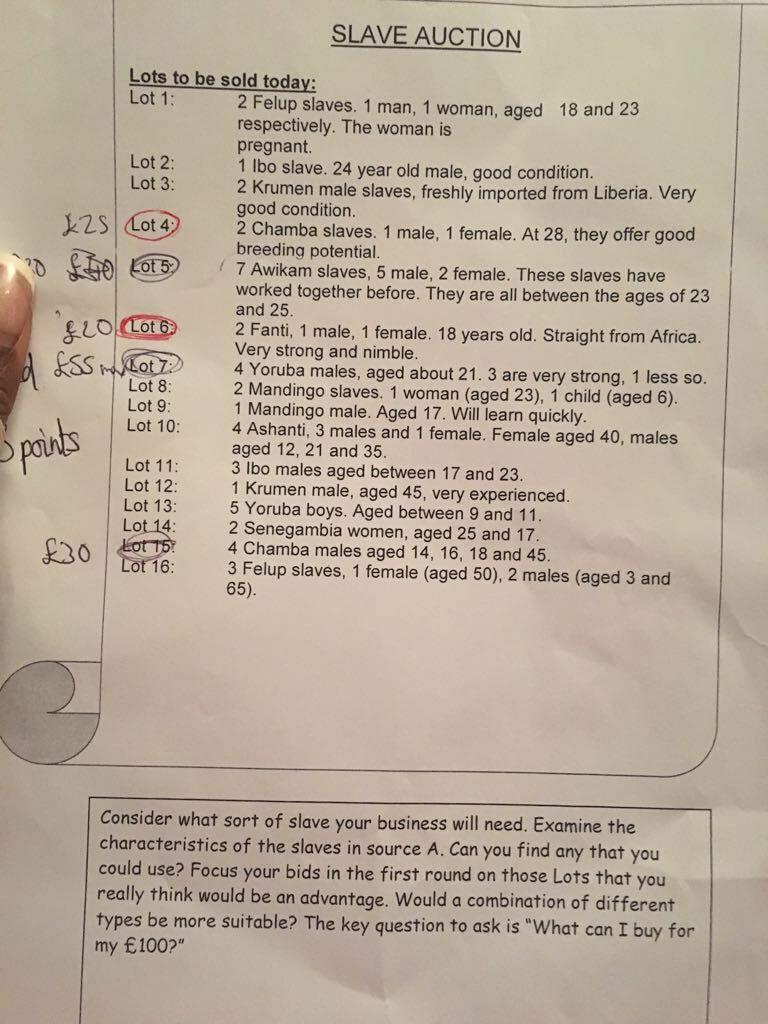

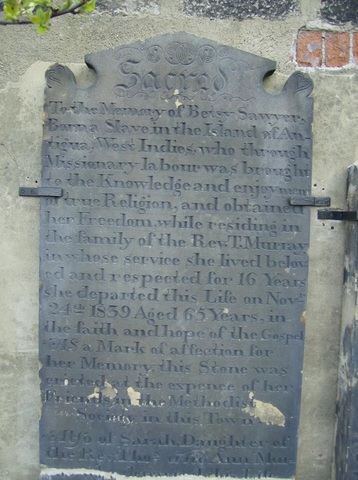

The “slave auction”

Reading the title of this, I hope most people would be baulking already. However, in the last five years, I have heard of this kind of lesson being used in multiple history departments and the image above is not invented but actually came from a grammar school in the South East. Just as with the Holocaust example I gave last time, this type of activity can end up being done in multiple topic areas, but effectively involves role-playing an extreme power imbalance.

The reasons departments persist with “lessons” like this one are usually vaguely couched in terms of empathy, and the need to clarify complex concepts like chattel slavery. However, more often than not they are promoted for their “interactive”, or “engaging” elements. Indeed, one non-historian described seeing such a lesson to me once as being “a good, fun way to get across a difficult idea.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed