To give you some context. We currently teach AQA's AS unit on Russia 1855-1917. This feeds into an A2 on the USSR 1941-1991. Under the A Level changes we have opted to go for the new unit which covers 1855-1964 (splitting at 1917 for the purposes of AS examination). On the surface this seemed like the obvious choice and the specification document seemed to bear this out - covering areas we were already comfortable with teaching. However it didn't take too long before we started encountering issues in planning the AS portion of the unit.

The first major planning issue we encountered was the fact that the new 1855-1964 course focuses much more on change over time and thematic development. The exam questions cover much longer periods and ask students to make judgments over time. For example:

- "The lives of the Russian peasants were transformed in the years 1928 to 1964." How far do you agree? (25), or

- "The Russian economy was transformed in the years 1881-1917." How far do you agree? (25)

After some discussion we arrived at the conclusion that we wanted the students to develop a clear understanding of an unfolding narrative in the key thematic areas (political authority, the economy etc.). But we were also keen not to let the themes drive the whole course. Having taught thematic courses in the past (Italian Renaissance, I am looking at you) I have found that they can become very dry and students lose all sense of the links between different parts of the course - seeing each theme in isolation. This actually touches on an aspect of Key Stage 3 teaching we have been focusing on, namely getting kids to see that change and continuity flows are interdependent even when they seemingly operate in different ways, or even go in different directions.

We wanted to create a situation where each piece of the course helped to build a broad contextual picture of Russia 1855 to 1964 in which the themes could be comfortably situated. As such we opted to go for a hybrid model in which we told chunks of the narrative thematically, structured around key questions to create engaging and meaningful units of study. Knowing how the history actually unfolded was crucial in making this decision. We were convinced that students would never get a proper understanding if they took a fully thematic or fully narrative approach. This ties in with the work Hammond has been doing on developing students' contextual knowledge so that they are able to "flavour" historical arguments with their knowledge.

Putting it into Practice

Returning to the specification document to begin the planning process proper proved to be of limited help. As the extract of the AS course (below) shows, the content has been arranged in broadly thematic sections but with little consideration of how these would create a coherent narrative. Notably there seems to be little consideration for how students might develop their understanding of context. Taking the points in order set out here we found ourselves running into issues such as:

- Is it possible to teach opposition groups and their worries without first knowing how Russian society and economy had developed?

- Does it really make sense to look at issues in the Russian empire before understanding issues at home?

- How does one teach about Duma government and the 1905 Revolution if students don't yet have a grasp of the demands of liberals, socialists, Marxists etc. between 1894 and 1904?

- Robert Service's, The Penguin History of Modern Russia

- Orlando Figes', Revolutionary Russia

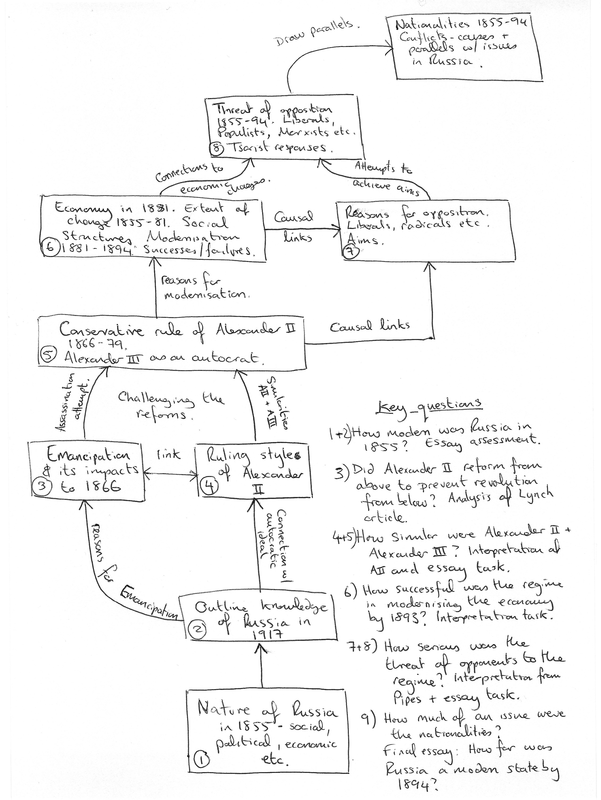

Once we were happy we had a good knowledge of the course, we looked to place the themes in as sensible an order as possible - sometimes following the thematic issue (eg. oppostion) and other times following the narrative (breaking the focus on Alexander II in 1866 for example to reach mid-point conclusion). All the time however we were considering which knowledge would be pre-requisite for understanding the next theme or section of the course ie. which knowledge would be needed to flavour and inform the claims students would later make. We were effectively constructing a frame upon which the themes could be comfortably hung. During the planning process were were constantly asking questions of each other such as:

"If we teach opposition before the economy, can the students really get to grip with the issues driving the Populists?"

"If we don't look at opposition until the end, do they miss the relationship between autocracy and opposition?"

Whenever such questions came up, we were able to fall back on our knowledge of the key issues and arguments in Russian history to help us map a path through:

"Well they surely have to know about the tsarist views on autocracy before they can tackle opposition because Figes argues that it was a desire to maintain autocratic rule which drove almost everything Alexander III did..."

"We have to teach the economic developments before we teach the Populists because they are essentially responding to the declining conditions in the countryside..."

The result was a curriculum map which we felt allowed students to develop thematic understanding alongside the historical narrative.

The Final Product...A Work in Progress

The plan below shows what we eventually mapped out. This is the outline plan for the very first section of the course on Russia 1855-1894. Each block is a section of content which helps embed a particular theme. With one block embedded the teacher can then move up to the next block. In some cases multiple routes are possible, but progress cannot be made to higher levels before all the blocks on one level are finished. In this case you can see that we felt a knowledge of Russia in 1855; Russia by 1917; Emancipation and its impact up to 1866; and the ruling style of Alexander II to 1866 were all prerequisites for pupils to tackle the unit on Alexander III as a ruler and thereby the theme on political power and authority 1855-1894.

(A full pdf of this image is at the bottom of the post.)

- A clear thematic overview 1855-1917 (and then on to 1964).

- A focus on historical interpretations as drivers of historical enquiry questions

- An increased focus on students reading historians and developing their own, supported views on the key topic areas.

- Students engaging meaningfully in the historical debates.

I will cover these issues more in a future post. All comments on this post appreciated. Oh... and sorry if The Key: The Secret is now earworming its way into your brain!

Mr F

| russia_1855-94_planning.pdf |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed