Tackling the issue of oversimplification

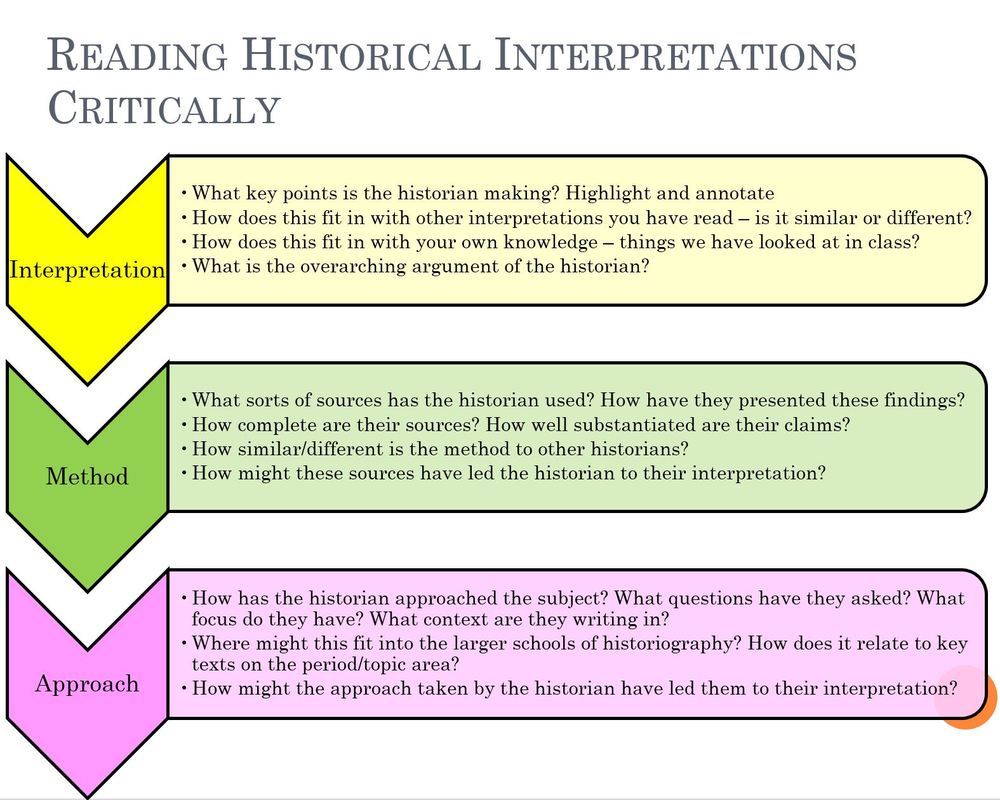

To prevent students from falling back to a lazy cynicism about historical interpretations, I like to use the following approach which I term the “IMA” approach to unpicking interpretations. This works best when students are asked to read extended extracts from historians, or even whole articles. It certainly would not work with tiny gobbets. In essence, the process involves:

- Identifying the historian’s INTERPRETATION - Main points and overarching argument

- Engaging with their historical METHOD - What sources of information have they chosen? How have they chosen to work with these? Etc.

- Looking for clues about their historical APPROACH - What sort of story do they want to tell and why?

Latterly, I have encouraged KS4 and 5 students to look at all historical interpretations in this manner; highlighting interpretation in yellow, approach in pink and method in green. Taking such an approach means that students are forced to engage with the arguments of an historian, as well as considering the contextual information in balance with the methodologies employed.

Anyone who knows me will be aware of my passion for the American West. This approach came out of the need for students not to reject older interpretations of Westward expansion, even though many of these were heavily influenced by dubious political goals and personal moralities. Using such an approach meant that students were able to assess and evaluate controversial, “Old Western” historians like Ray Allen Billington with more inclusive “New Western” interpretations successfully. Over time, students were able to see that, whilst Billington’s concern with white settlement got him to focus primarily on white, male, pioneer evidence, his engagement with this evidence was actually very comprehensive. Rather than reject Billington outright as a mypopic racist, students were able to comment on his limitations in exploring the very real experiences of Mexican, black, Indians, and female actors in the story of the West. You can see an example of an analysis of a Billington chapter HERE and of a more recent Stansell & Faragher one HERE.

I think it is also useful for students to spend some time reflecting on historical interpretations as a way to help them reflect on their own studies and research into a topic, or as a starting point to explore the curriculum area in more depth. One approach I have particularly enjoyed using is to get students to find points of assent and disagreement between different historians. To do this, I ask students to read and then write summaries of historical interpretations (using one of the methods above) and stick these on large sheets of paper. They then draw links between historians who make similar points, and note down major disagreements by linking opposing points in red. As a final task, I get students to find evidence which would support or challenge each interpretation and add this on as post-it notes. You can see this in action below and find a set of resources relating to interpretations of Gorbachev’s reform of the Soviet Union HERE.

Another variation is to get students to research an extended piece by an historian, then hold a debate where students have to be in character as their chosen historian. They are only allowed to contribute points to the debate which their historian would agree with.

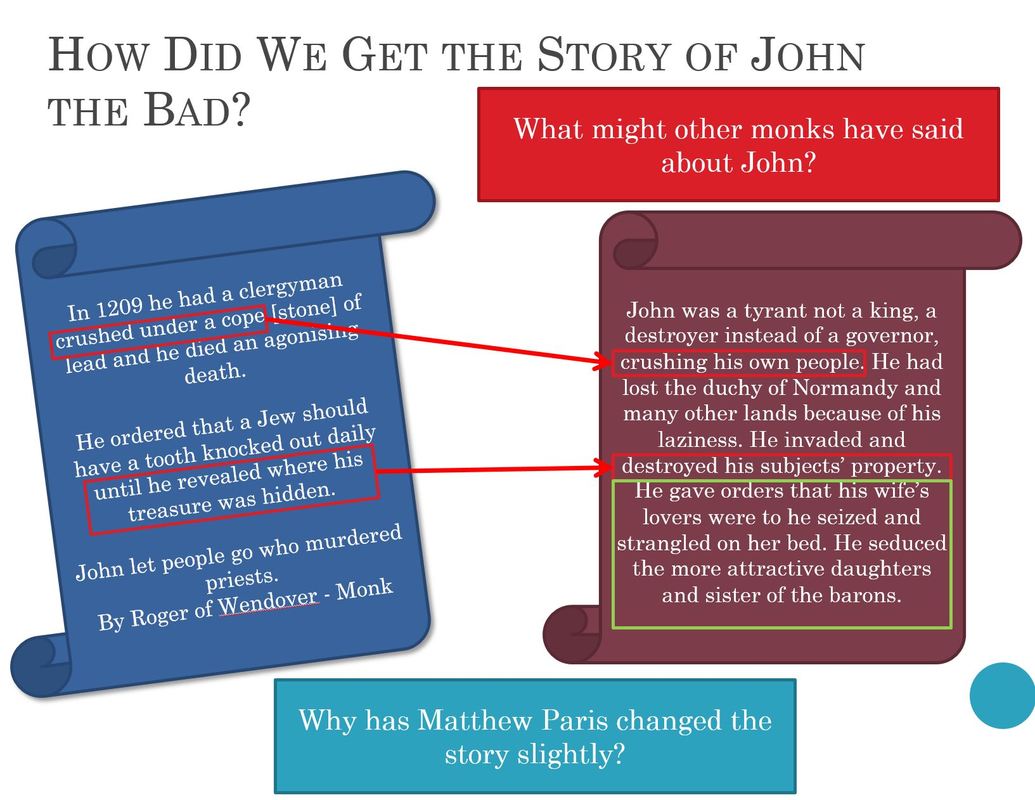

In many senses, I am not sure younger students need to take a different approach. All of the methods described above can be used with Key Stage 3 as long as the teacher is careful in the selection of the interpretations and the complexity of the arguments. I have found that Ladybird books make an excellent starting point to use some of the methods above with Year 7 pupils for example. If we can make the use of interpretations in sequences of learning a matter of course, and a fascinating part of study, then we can accustom pupils to engaging with them over time.

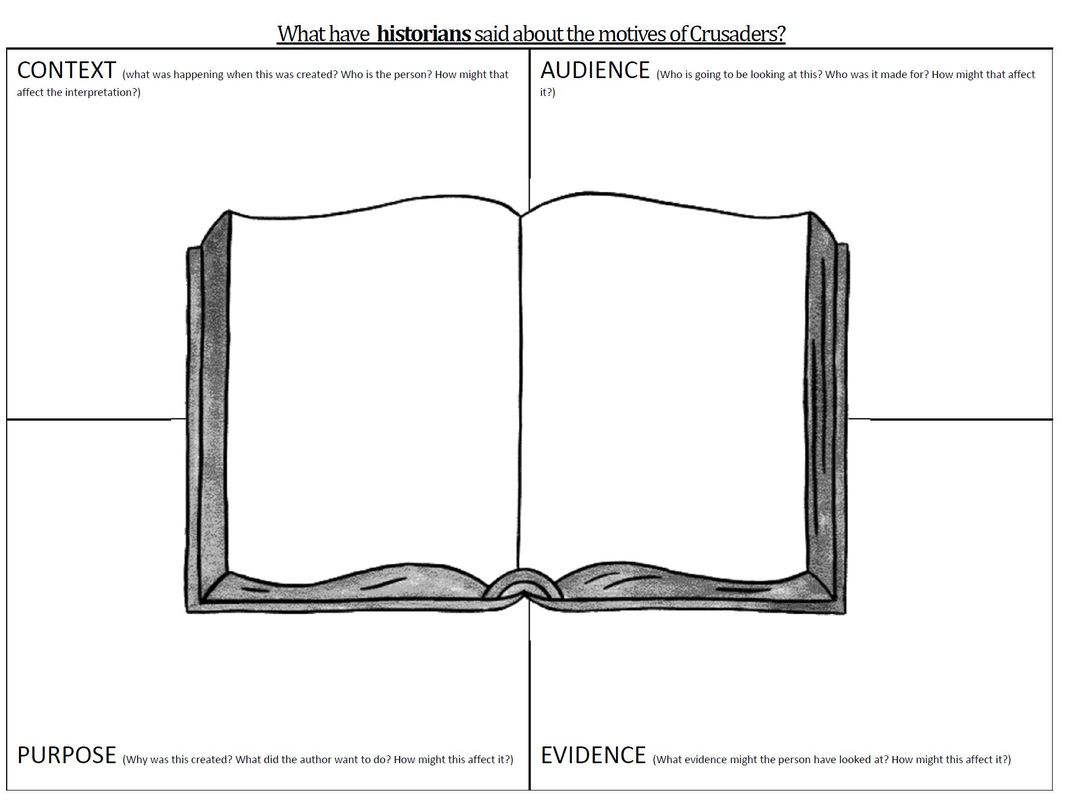

There is a good case to use a less text-heavy version of the note taking grids to help students see the layers of analysis more readily (interpretation in the centre and analysis around the outside). The graphic organiser below comes from a series of lessons designed to introduce students to historical interpretations in a topic on the Crusades. There are a few niggles with this scheme as it was written back in 2011 (notably distinctions between interpretations and representations are not as clear as I would have liked), but the general principles are effective. You can find the full sequence HERE.

Moving On

I hope at least some of these suggestions are useful ways for history teachers and departments to begin reconsidering how they approach historical interpretations in the classroom. As ever, if you have any questions or comments, please do let me know below on or Twitter @apf102.

Anyone looking for further approaches should definitely look at Teaching History’s “New, Novice or Nervous?” page here: http://www.history.org.uk/secondary/resource/7831/new-novice-or-nervous-interpretations . I would particularly recommend Card’s articles.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed