Keegan has not done much to outline her position on education reform yet, however she has stated that she intends raise ‘quality’ across the system by focusing the needs of those in comprehensive schools. At the very least, this hints at a social justice agenda involving all schools – a distinctive break from the grammar school focus of many of her predecessors. Indeed, she seems to be taking a similar tack to former (and now current) Schools Minister Nick Gibb, who described comprehensive schools as ‘engines of social mobility’.

But how does Keegan intend to improve school standards to enable this social mobility agenda? The return of Nick Gibb I think gives the strongest indication of Keegan’s likely approach, not least because she described Gibb as having done a ‘brilliant job’ since 2010. If this is true, then it is likely to mean a continuation of centrally imposed, curriculum-focused reforms. In this blog I hope to highlight the limits of continuing in this manner and, with reference to the history curriculum, and using the work of the Schools History Project as an example, suggest some alternative means to enact meaningful change in the education system.

(If you’d like to know more about the work of the Schools History Project, please do sign up here to receive updates on upcoming projects.)

Improving ‘quality’ AND doing justice?

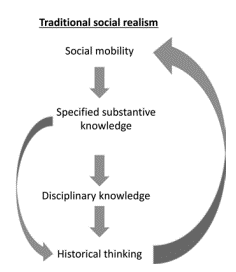

In their recent chapter in Chapman’s ‘Knowing History in Schools’, Smith and Jackson outline what the ‘social mobility’ approach entails for history education in particular.

In terms of the history curriculum this has been framed as providing young people with a body of powerful knowledge comprised of agreed-upon disciplinary knowledge and a body of substantive historical knowledge (framed by the DfE as ‘cultural capital’). This knowledge in turn is seen as being regulated by the academic discipline of history as the source of ‘authority’. In this conception of justice, it makes sense to deliver that knowledge through centralised systems – doing do maximises the chances that all pupils will get access to that knowledge.

Since 2010, at the same time as allegedly decentralising school control via the Academies programme, there have been a raft of centrally directed measures, most of which have attempted to exert greater control over the history curriculum content taught in schools. These measures have included: the creation of a new ‘Island Story’ National Curriculum; endorsing a new range of ‘knowledge-rich’ textbooks; spending £7.7 million on commissioning ‘knowledge-rich’ schools to create ‘oven ready’ curriculum resources; encouraging the development of a subject-focused Ofsted framework; convening an expert group of historians, consultants, academy chiefs, and the odd teacher to draft a model history curriculum; and an attempt to create a complete set of online curriculum resources via the ex-DfE-funded Oak National Academy.

So, what lessons should the new Secretary of State take from all this? Where have all these centrally directed attempts to transform history teaching left us? The reality is that for too many children, history is still seen as too complex and too irrelevant to study beyond the age of 14. Nearly 40 years after the Rampton Report, children with heritage other than white, English report the curriculum still does little to represent them. Indeed, some have walked out in protest at the history they have been taught. For those who continue with their history education the examinations are so content heavy and dense that a significant number of children barely score a dozen marks over three exam papers after two years of study. Those with SEND seldom continue history beyond the age of 16. The potential for history education to contribute to social justice real, but it is simply not being realised. If the children’s experiences of history in the classroom are improving at all, it is despite—rather than because of—these centrally imposed changes. The real question is why?

Lucy

First, a story. Seven years ago, my wife left her career as a Primary teacher and began training to be a priest in the Church of England. One of her placement churches as a trainee was on an extremely economically deprived estate on the edge of Bradford. She spent four years there with her mentor, Lucy (not her real name).

When we first started attending the church, not long after Lucy’s own arrival, the congregation felt a little lost. They were all part of the local community and wanted their church to grow and thrive, to bring something of worth. But the socio-economic deprivation of the area felt like an insurmountable barrier to access. Naturally they looked to Lucy for leadership.

Last Sunday, three years after we last went to the church, we went back to mark Lucy’s retirement. The change we saw was, if you’ll pardon the phrase, miraculous. We saw a growing congregation. We saw a group of people confident in their faith, and confident to talk about their faith openly with each other, and willing to throw the doors open wide and invite others along too. We saw a group of people tackling the needs of their own community through: a messy church for children; toddler groups; coffee mornings for the lonely and those new to the community; a food bank; a clothing bank; a bedding collection and delivery service; and organising regular meetings with local councillors to give the estate a voice. No-one was kidding themselves that the problems their community faced had gone, but now they felt able to begin to tackle them. More than this, those once quiet congregation members who seven years ago would have sat in their seats, drunk a coffee and gone home, were leading the service, talking about and celebrating their good news, sharing their troubles and their prayers. They had become a confident, outward looking beacon of hope and transformation.

What did Lucy do that enabled the congregation she led to develop the confidence and ability to begin to transform their community? You might think that the answer lies in charismatic leadership, sharing inspirational visions, providing the solutions. But in fact, the opposite is true. Lucy’s success was not in leading the charge, not in directing from the centre, but in ensuring every member of the congregation felt empowered to meet the needs they saw in their own community. It was a form of leadership which began in the community, then guiding and supporting members of that same community to meet those needs, and begin a process of transformation.

Are we doing justice?

As we have seen above, churches, just like schools, can be major drivers of social justice. Yet Lucy’s is a very different vision of social justice than the one which has dominated thinking in education for the past twelve years (and longer). I think there is much to learn from this approach.

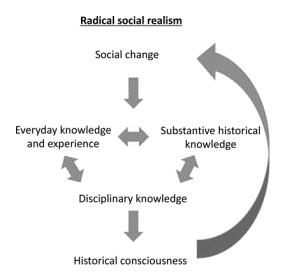

Smith and Jackson provide a second outline model for social justice – one whose goal, much like Lucy’s, is not ‘social mobility’ but ‘social change’.

In terms of the history curriculum then, pursuing the goal of ‘social change’ means being aware of the knowledge and experiences brought to the classroom by young people from within their communities. It means acknowledging that what counts as powerful substantive knowledge is only so through negotiation. This fundamentally questions the idea that the discipline of history should act as the sole source of ‘authority’, with teachers acting as a bridge between two worlds. The ‘social change’ model views the discipline of history as just one source of authority, balanced by broader understandings of history and memory, the voices of the community, the voices of pupils, and the educational knowledge of teachers themselves. Here teachers are negotiators between many worlds: experts rather than conduits.

A model for transformational change

So, what would it look like to enact transformational change from a community level in history education? Here I want to talk about how the work of the Schools History Project provides one powerful example of this approach.

Since 1972 the Schools History Project has been encouraging teachers to consider how school history can meet the needs of young people in their own communities. From the outset it was attempting to tackle those feelings of disconnection and dissatisfaction noted earlier in this blog. The Project recognised that children needed to find a connection to history in order for it to have any transformative power at all. The project’s aims were codified in a set of Principles which were agreed upon centrally but broad enough to shape action locally. If Gillian Keegan wants to harness the power of education (and history education in particular) to be an agent for social justice, then I think is it important to understand how these principles have acted as a means of professional empowerment and community transformation.

SHP Principles have been a spark to action for thousands of history teachers. They have encouraged history teachers to focus on the local historical environment, to connect history to the lives and experiences of young people, to develop children's love of history, and to empower young people to know their world from the intensely local, to the national and international. The Principles have shaped GCSE examinations, teacher education courses (both nationally and internationally), and have underpinned textbooks and resources which have had enormous reach. The Principles have been an inspiration for teaching conferences, bringing people together from vastly different school communities to discuss what tranformative history teaching could look like in their contexts. They have empowered history teachers become authorities on the teaching of their subject, broading and deepening their impact on social change.

(I really wanted to write about all the examples I have come across of the imapct of SHP thinking on pupils and commnities, but space just won't allow. Please do look at some of the amazing workshops linked above if you have time for a flavour, and I sincerely hope SHP colleagues will share their own examples too.)

Fifty years on, the Schools History Project (SHP) is still guided by a set of Principles which seek to advance the cause of social justice by empowering teachers to meet the needs of the young people in the communities they serve.

School history should be meaningful to young people and help them understand the world they live in

- SHP has always sought to promote history which seeks to explain the forces which shape the present day and the unique circumstances of specific communities. It recognises that what counts as history starts at home as much as in the halls of academia.

- For many children a fascination with history begins when they first appreciate the historical nature of the environment around them. This Principle celebrates what is local but also helps young people recognise that history is all around them wherever they go and wherever they have come from – it is part of the fabric of our identity as well as our heritage.

- SHP has always maintained that young people should not just know about history but also know how historical claims are made. More than this however, SHP teachers have sought to help young people develop their own views and ideas about historical issues and even to engage critically with what “doing history” actually means. In recent years especially this has meant challenging notions of who counts as an historian – opening up worlds of oral history, community history and Indigenous ways of knowing.

- In the last ten years there has been a noticeable narrowing of the history curriculum. SHP recognises that meeting community needs means reflecting the true breadth of the histories which make up modern Britain. It also challenges teachers to engage with the decolonisation of the curriculum to remove damaging framings which have harmed communities and wider society for far too long.

- Understanding our world means being able to navigate the broad-brush strokes of a thousand-year story of migration, and also being able to engage in the messy detail of the historical records surrounding the Bristol Bus Boycott, or any number of other events with meaning to a specific community.

- This Principle encourages teachers to see enjoyment of history as a worthwhile end in its own right. It asks teachers to consider how challenge can be kept high whilst enabling every child to take part – a challenge which demands a focus on pedagogies as well as content. This Principle says that it is not acceptable to create history which is only for the higher attainers, or those without additioanl needs, or those who happen to be interested in the kinds of history which are classed as 'cultural capital'. It asks every teacher to consider what is life enhancing for pupils in their own context and how this might lead to greater justice for all. It is only by making this an explicit aim that we increase the likelihood that young people value the subject and benefit from is transformational potential.

A new challenge

The role of a Secretary of State for Education is a complex one. There are many elements to promoting social justice. History education is just one part of the picture. However, each and every school subject plays a role. Our history curricula can either help us move towards justice for our communities, or they can stand in the way.

The Schools History Project approach and its Principles do not provide easy answers or simple solutions. In fact, SHP Principles pose a series of challenges for teachers in relation to the needs of the young people in the communities they serve. But what is wonderful about them is that they are both a challenge and an invitation. Anyone can become part of the School History Project family, just by committing to put the Principles into action. Those who do will find themselves part of a movement which is committed to empowering history teachers to enact real social transformation through their work. The DfE can continue to try to ignore or side-line such approaches by continually imposing new top-down measures, or it can choose to engage with the mission of ‘social change’ and allow movements like SHP (and many others) to thrive. Either way SHP will continue to welcome and support all teachers who want to continue that transformative work. Together #WeAreSHP.

Note

The Schools History Project is currently working on a project to enable schools to share their own principled curriculum models as an alternative to the Model History Curriculum. There are also a range of exciting projects on the horizon, as well as a range of other work listed below.

If you’d like to know more about the work of the Schools History Project, please do sign up here to receive updates on upcoming projects.

Current work & projects:

- Annual history teaching summer conference at Leeds Trinity University

- Annual early career history teaching online conference

- OCR History B GCSE Specification

- Key Stage 3 textbooks based on SHP Principles

- GCSE textbooks based on SHP Principles

- A Level textbooks based on SHP Principles

RSS Feed

RSS Feed