Principal Skinner: Some sick individual has stolen every "Teacher's Edition!" |

Needless to say, many of these lessons ended up being incredibly dry, poorly conceived, and of little use to anyone. It took a long time and a lot of courage (largely as a result of being the only history teacher in a small school) to realise that the lessons where I had excellent subject knowledge were always the best ones. Even so, I had been set back a long way (as my ex-colleagues noticed when I tried to teach the French Revolution at the start of my THIRD year of teaching – I was even mistaken for an NQT because of this.)

Now, let me be clear. I am aware that teaching places huge demands on people, and that having a detailed knowledge of all subject content is a job that is far too big for a single year (indeed I am still developing areas of my subject knowledge now). This is a very good case for extending ITT over two or more years, rather than the current nine months. I am also aware that there will always be upsets in times of rapid curriculum change. I wonder how many of us spend the summer of 2013 frantically researching the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy or the Glorious Revolution for example? However, there should be a minimum standard which pupils, even at Key Stage 3, should be able to expect our knowledge reaches in order for us to put ourselves forward as teachers.

So here is the million-dollar question: should I set myself up as a guitar tutor and start earning some extra cash on the side? Clearly the answer to this is an emphatic no! The reasons why are almost so obvious that they don’t need saying, but here we go:

- I can play a handful of main chords, but I have learned a lot of bad habits which means that I find almost all barre chords very hard to play. If I were to teach someone else, I would have no way of helping them to avoid this error.

- I can read guitar tab but cannot read music at all, meaning that I would struggle to teach anyone to play as part of a bigger group.

- I understand the basics of chord shapes but couldn’t explain why chords are as they are, or why dropping a fourth finger on an Am turns it into an Am7. As such I have no appreciation of how I could vary chord structures beyond simple trial and error – not a great body of knowledge to impart.

So what level of knowledge would I expect from someone who teaches guitar? Actually, this is very hard for me to define as a non-expert. It is why asking pupils what they think of their teachers (or non-specialist inspectors to observe outside their subject area?) is such a problematic way of assessing teacher competence. Ideally, the qualities of a great guitar teacher should be set down and outlined by someone who is already a great guitar teacher. The kinds of things I might expect however would be:

- A full knowledge of the theory and practice of playing the guitar. This would involve knowing how different aspects of guitar playing theory link together and the knowledge of how certain building blocks allow for later progress (eg. Why particular finger patters or a particular way of holding the guitar neck?)

- An ability to communicate this knowledge effectively and without developing bad habits or misconceptions in their students.

- A commitment to continued personal improvement as a guitar player and guitar teacher – not just in method but in their own knowledge .

So how do we address this issue? I think there is a role for both ITT tutors and subject specialists in schools in setting out expectations for professional knowledge very clearly. The best subject mentors I have worked with will give their trainees recommendations for works to read to extend their knowledge and encourage them to find ways to bring these into lessons. The best mentors will also reward and recognise where trainees have taken the time to “know their stuff” even if the practicalities of the lesson did not go to plan. We also have a huge responsibility at the level of ITT as well. Learning how to teach history is not a collection of generic skills such as “planning” and “assessment”, everything should be connected to what we teach – “planning a causation lesson on the storming of the Bastille” or “assessing understanding of the significance of the fall of the Berlin Wall” for example.

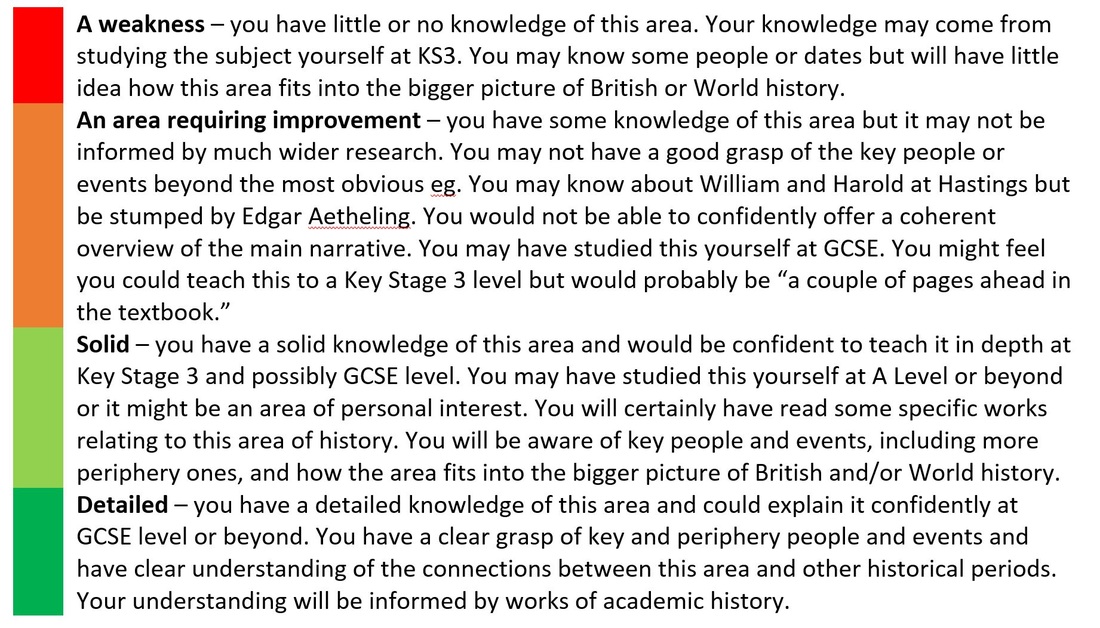

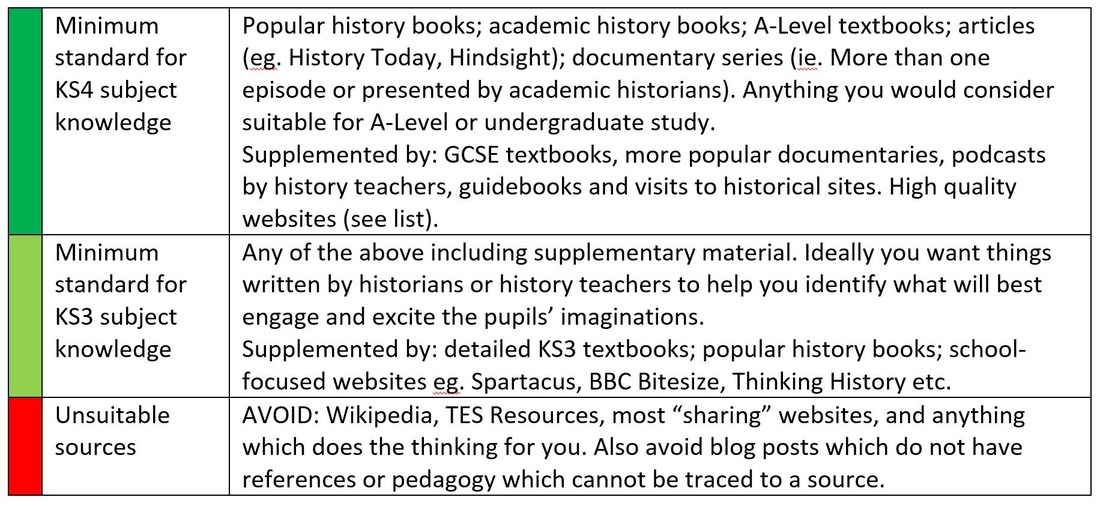

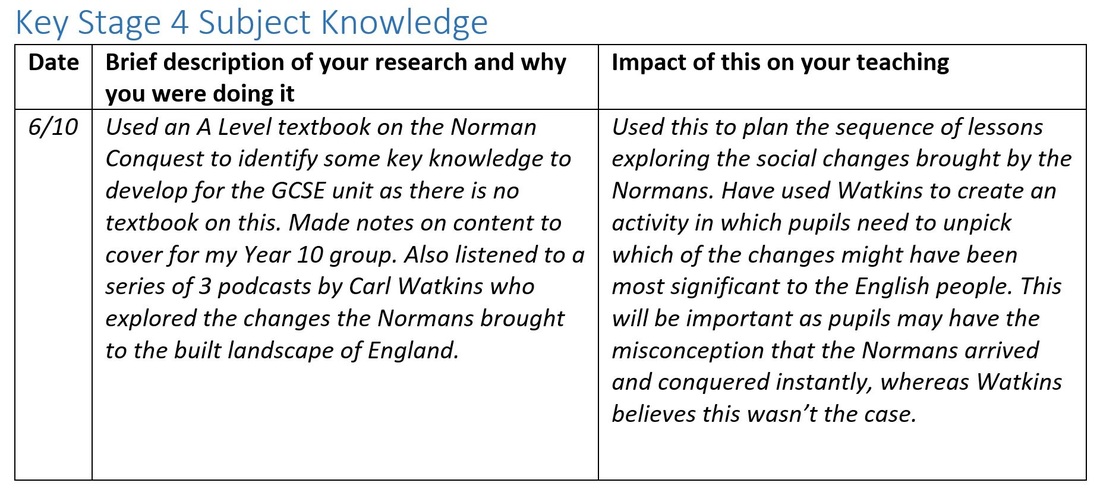

This year I am asking my trainees to identify their own areas of strength and weakness (not unusual in itself) so that they have an initial awareness of what might constitute solid knowledge for teaching. I am asking them to grade themselves on core areas of content as follows:

“The subject knowledge of the specialist history teachers in the secondary schools visited was almost always good, often it was outstanding and, occasionally, it was encyclopaedic. Inspectors found so much good and outstanding teaching because the teachers knew their subject well.”

Since then we have moved to a system where many of those schools are now key in the training of the next generation of history teachers. The expertise is certainly there, so uit is crucial that the subject knowledge focus is not lost in the sea of genericism which tends to flood both schools and ITT institutions. I sincerely hope and believe that we can rise to this challenge as a history community.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed