If you are new to the concept of ‘powerful knowledge’ here is a brief crash course (you might also like to read this). In Young and Lambert’s phrasing: “knowledge is ‘powerful’ if it predicts, if it explains, if it enables you to envisage alternatives” (Young and Lambert, 2014, p. 74). However, this is not the full picture. There are other criteria Young uses to define ‘powerful knowledge’:

- PK is distinct from everyday knowledge;

- PK’s concepts are systematically related to other concepts or ideas within a discipline

- PK allows generalisations and thinking beyond particular cases or contexts;

- PK is developed within specialist disciplines or fields of enquiry, and is therefore peculiar to the discipline

- PK is the product of broad disciplinary agreement;

- PK is always provisional in relation to the truth processes of the discipline.

Powerful knowledge and curriculum

Young and Lambert make the case in “Knowledge and the Future School” that the identification of ‘powerful knowledge’ is an important tool for considering curriculum construction. They argue that the concept of ‘powerful knowledge’ might help schools “reach a shared understanding about the knowledge they want their pupils to acquire” through the collective wisdom of the various disciplines (Young and Lambert, 2014, p. 69).

The problem is, the more I see people discussing ‘powerful knowledge’ in the curriculum, the more I tend to see discussions of the ‘knowledge of the powerful’. I have lost count of the number of times I have seen very traditional, Anglo-centric, politically focused history curricula put forward as ‘empowering’ or living out the principles of ‘powerful knowledge’. This to me is a huge problem because it lends an unwarranted, and seemingly politically-neutral justification to an approach to curriculum which is actually heavily ideological. Yet the concept of ‘powerful knowledge is so ill defined in history, that it allows this kind of abuse. Indeed, I would go further and say that the term itself gets in the way of more important aspects of curriculum construction like being open about our ideologies, principles and aims in our content selection.

Defining ‘powerful knowledge’

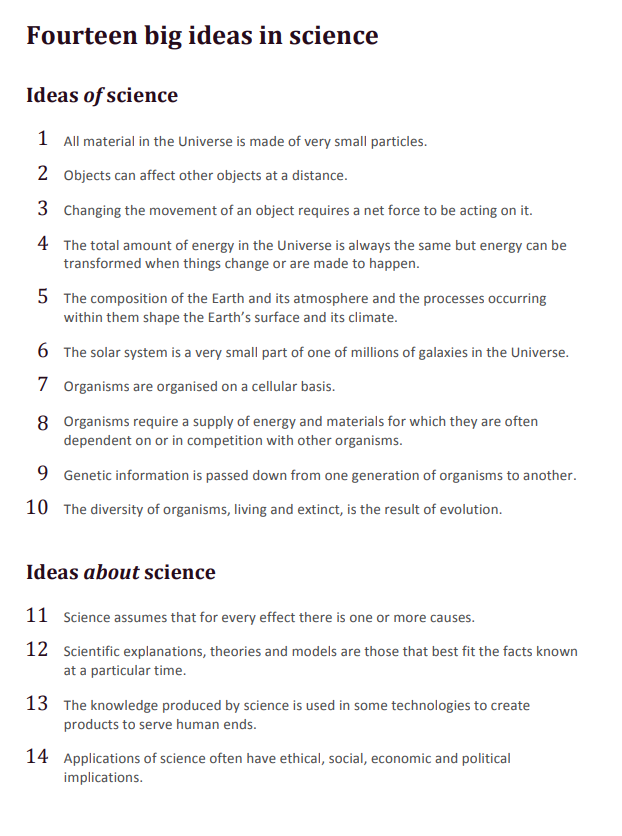

Young’s concept and his message are certainly compelling. ‘powerful knowledge’ seems to offer a means to design a curriculum without the messiness of considering our own philosophies and motivations. The fact that certain knowledge is agreed upon by a broadly cohesive and stable grouping appears to be a good way to transcend the difficulties of whether to teach Henry V’s victory at Agincourt or a social history of the teaspoon. The example below, taken from science (ASE), does a good job of illustrating how this might work in practice. Here a set of ‘agreed-upon’ statements are presented as the founding ideas and processes of science. So the question is, could we produce something similar for history?

In the science example above, the ten “ideas of science” are all substantive. If we take the same approach with history, then we are forced to ask: what is uniquely powerful in the vast swathe of content and ideas which one could teach in human history? One would also be forced to ask: should that ‘powerful knowledge’ be outlined as powerful events, powerful substantive concepts, or broader, powerful historical statements?

Events: Even a simple set of tests reveals the weakness of trying to define ‘powerful’ historical knowledge in terms of events. Is the Peasants’ Revolt ‘powerful knowledge’ or the events of the English Reformation a better example of ‘powerful knowledge’? It is certainly difficult to understand the British Civil Wars, or the Enlightenment, or any number of other things without first covering the developments which took place in the English Reformation. However, this supposes that the curriculum should also contain the latter two items. A history teacher in in Beijing, or Stockholm, or Tirana seems far less likely to be teaching about the British Civil Wars and therefore the explanatory power of the studying the English Reformation is instantly diminished. This seems so obvious as to be moot, but it is vital because one of the other core tenets of ‘powerful knowledge’ is that it needs to have broad explanatory properties for the discipline as a whole. Choosing any given set of events only reveals a power relative to other content being taught. Teaching the English Reformation is powerful in terms of understanding huge amounts of English, and wider British history, politics, economics, what it means to be British, and so on, but it is not universally accepted as ‘powerful’.

Substantive Concepts: Another approach might be to move away from a focus on events and to define particular substantive concepts to be learnt e.g. ‘democracy’, ‘empire’, or even ‘peasant’. Yet such concepts are not rooted firmly in the discipline of history, and therefore fail the ‘powerful knowledge’ test that truth should be established through the community of enquiry. ‘Democracy’ and ‘empire’ for example might be claimed by political sciences, or philosophy. Beyond this, history borrows substantive concepts from so many fields that to even begin to define the necessary ones would be half a lifetime’s work. Therefore, the core problem becomes one of selection. The choice of substantive concepts for study would necessarily depend on the overall shape of the curriculum, but could not determine the shape of the curriculum as Young and Lambert (2014) have suggested ‘powerful knowledge’ might.

Historical Statements: A more novel way of thinking about ‘powerful knowledge’ in history might be to attempt to generate ideas and concepts which transcend particular time periods or events e.g. “people are prone to challenge authority”, or “revolutions lead to change”. However, this throws up new problems. The first is already obvious: neither of these ideas is universal as neither applies in all cases in history. Second, it seems doubtful that even a handful of historians would be able to create an agreed upon list of universal concepts, let alone the discipline of history as a whole. Even if such a process were able to identify a selection of ‘powerful’ ideas to agree upon, there would still be no consensus on which events in history might best convey or exemplify them, so the problem of content selection resurfaces.

Can historical knowledge not have power?

Does this mean that particular substantive knowledge has now power? No, I just don’t see how any substantive knowledge in history can be ‘powerful knowledge’ in the way Young has defined. Much sensible discussion about knowledge in the curriculum has revolved around the notion that knowledge can have generative power (Counsell, 2017, 2016; Hammond, 2014). This I think is an important idea, but it distracts us from the core issue of what should be included in the curriculum in the first place. Any justifications of knowledge to include in a history curriculum because of its generative power end up being self-referential. Some knowledge definitely has more generative power than other knowledge within particular curricular constructions. If I am teaching students about the first three Crusades (or Frankish Invasions), then it is definitely more powerful for them to have grasped the concept of religious belief in the C11th beforehand, and to see how this developed the idea of “Just War”, than it is for them to have explored the death rites of the Inca. This idea of knowledge which helps underpin future knowledge is a central and important part of curriculum design, and is something Rich Kennett and I wrote about recently (Ford and Kennett, 2018). However, this is knowledge which has ‘curricular power’ rather than ‘powerful knowledge’. The power is relative to the curriculum which has been designed; it does not have the universality of the concept of say “all material in the universe is made of small particles” in science. Change the curriculum and the internally powerful curricular knowledge would change too. The only possible solution to this might be to create a list of all the possible events and ideas which have generative power in the whole of human history, and then see if the entire discipline could agree upon them, but I hope the futility of such an endeavour is obvious without further explanation.

Ideas about history: ‘powerful’ disciplinary knowledge?

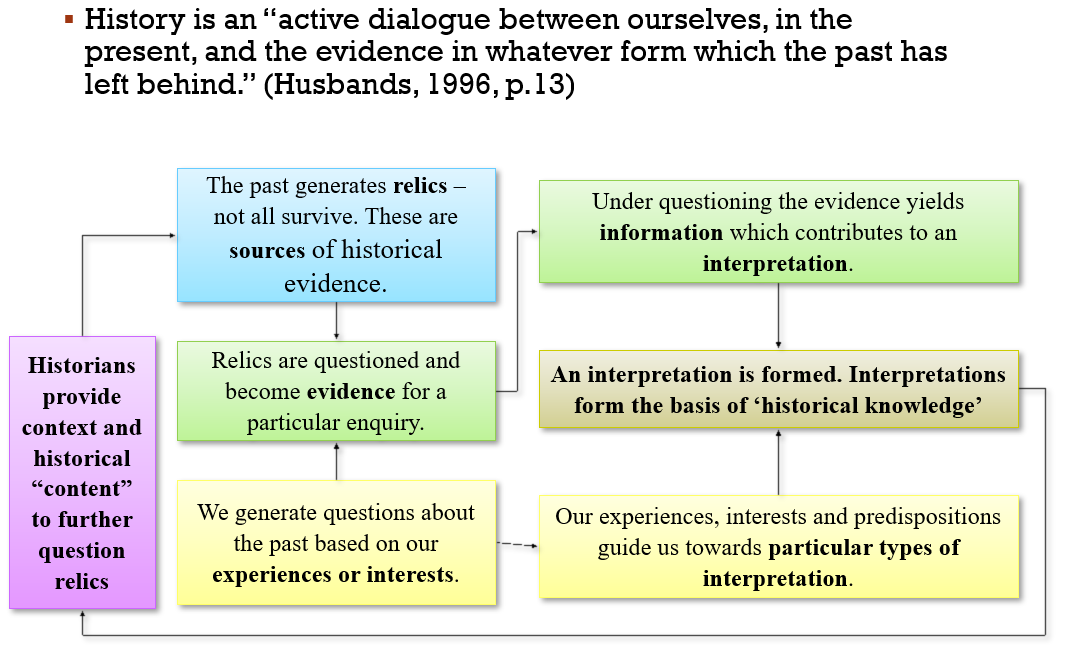

Where I do think we might make more of a case for ‘powerful knowledge’ in history is in terms of the disciplinary aspects of the subject. Notably, in Young’s terms, it is powerful to know how a discipline seeks ‘truth’, and important to know the processes by which such is ‘truth’ is created (Young and Lambert, 2014). I think it would be fairly safe to say that most historians would agree that historical enquiry is the process by which historical claims are generated and challenged. I am still indebted to the wonderful work done by Ian Dawson to this end (Dawson, 2018, 2015). To take this further, it might be considered ‘powerful knowledge’ for students to know that historians are always on a trajectory from knowing little, with an aim to know more; that they engage with evidence, ask questions, develop and refine hypotheses, and continue in this vein until they are satisfied that the shape of some tentative historical truth has begun to emerge. This process is nearly outlined also by Chris Husbands in his now classic “What is History Teaching” (Husbands, 1996).

- Questions around why things happened

- Questions around how things changed or stayed the same

- Questions around the impact of events

- Questions around the similarities or differences between people’s experiences

- Questions around appropriate generalisations

- Questions around the nature of historical evidence

- Questions around the ways in which the past has been interpreted or represented

- Questions around historical significance

All of these types of question have rich traditions within historical study, but also in the study of school history. We might therefore offer a tentative definition of ‘powerful knowledge’ in history as: ‘powerful processes’, ‘powerful questions’, and ‘powerful debates’

However, even with this more promising lead, defining ‘powerful knowledge’ as disciplinary knowledge still raises problems for curriculum construction. In fact, defining ‘powerful knowledge in this way moves us back to a scenario where substantive knowledge might be downplayed in favour of disciplinary. It might be possible to make a case to base the entirety of a Key Stage 3 history on topics connected to the growth, development, and crises of the kingdom of Benin for example. The only thing which would prevent teachers doing this would be a moral judgment about the extent to which students should know the history of the nation in which they are currently residing. Such a justification might be perfectly acceptable, but it would not be supported via the lens of ‘powerful knowledge’. To put it another way, there is seemingly no conception of ‘powerful knowledge’ in history in which substantive content selections do not have to be justified in relation to other educational principles and aims.

Knowledge, power and principles

The point of writing this piece was to try to put into words some of the things I have been wrestling with for the last few years of my history teaching—, and PGCE— , career. I do accept that Young has provided a useful toolset to consider what we teach within a curricular construction. For instance, once we have selected our topic areas, we can gain a huge amount by looking at the ‘powerful questions’ historians are asking, and the ‘powerful debates’ they are engaging in to determine our focuses and choice of content. No study of the First World War should be happening in schools today in my view unless it is engaging with current questions over the diversity of the soldiers who fought. Equally, no self-respecting study of the American West should be taught through Turner’s Frontier Thesis, or Brown’s “Bury My Heart and Wounded Knee”, thereby ignoring debates about the West as a place, and the agency of Indians in the story of America.

However, I am ultimately concluding is that in most cases, there is no easy or objective way to select the content we include in history at the macro (curricular) scale; everything comes back to our philosophical justifications. Whether we like it or not, our educational aims and philosophies remain the bedrock of content decisions in history. We need to accept that we cannot outsource the task of choosing the outline content of our curriculum to ‘the Discipline’. Knowledge can only have generative power in a curriculum once its shape is already known. There is no universally powerful set of knowledge for students to understand via history. Therefore, we must ensure that whatever decisions we make are deeply rooted in the moral and ethical values which we hold to be central to education and to history education in particular. These hopefully come from engagement with a wider group of historians and history teachers, but we need to recognise them and be open about them. Marc Bloch once said that he “should like professional historians, above all, the younger ones to reflect upon [the] hesitancies…[and] incessant soul searchings of our craft. It will be the surest way they can prepare themselves…to direct their efforts reasonably” (1992, p.15). To add history teachers to this group would be a small leap. If history educators do not constantly ask questions about the nature of their subject and its principles, then the subject is nothing. Only through this process can we open history up to scrutiny and therefore justification.

References

Counsell, C., 2017. The fertility of substantive knowledge: in search of its hidden generative power, in: Davies, I. (Ed.), Debates in History Teaching. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London ; New York, pp. 80–99.

Counsell, C., 2016. History teachers’ publication and the curricular ‘what?’: mobilising subject-specific professional knowledge in a culture of genericism, in: Burn, K., Chapman, A., Counsell, C. (Eds.), MasterClass in History Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning. Bloomsbury, London, pp. 350–359.

Dawson, I., 2018. What do we want students to understand about the process of ‘doing history’? Exploring and Teaching Medieval History 109–112.

Dawson, I., 2015. Enquiry: developing puzzling, enjoyable, effective historical investigations. Primary History 8–14.

Ford, A., Kennett, R., 2018. Conducting the orchestra to allow our students to hear the symphony: getting richness of knowledge without resorting to fact overload. Teaching History 8–16.

Hammond, K., 2014. The knowledge that “flavours” a claim: towards building and assessing historical knolwedge on three scales. Teaching History 18–24.

Husbands, C., 1996. What is history teaching?: language, ideas, and meaning in learning about the past. Open University Press, Buckingham ; Philadelphia.

Young, M.F.D., Lambert, D., 2014. Knowledge and the future school: curriculum and social justice. Bloomsbury Academic, New York.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed