I have written about Fred previously, but in this blog I wanted to revisit the story of our first meeting and a conversation we ended up having about teachers and teaching. I want and tell it again now in light of the man, and the teacher, I came to know. I suppose it’s my way of saying goodbye, but also, I hope a way to share the wisdom of someone who I wish everybody could have met.

Lunch with Fred

I first met Fred in the summer of 2016. My wife has been visiting him for some time as he was a member of the local church and had recently lost his own wife, Sue. Just like Fred, Sue had been a teacher. She had worked with women in immigrant families in Bradford to help them learn English. Some of these women still came to visit Fred right until the end. In the summer Fred was often to be found sat on a lawn with a cup of tea and company whilst small children ducked in and out of runner beans or picked apples or pears in the garden.

One Sunday, Fred invited my wife and I along to lunch at a local pub. Before she became a vicar, my wife had been a primary school teacher, and I was in my first year of running a PGCE course. It was almost inevitable that the conversation would turn eventually to teaching.

You may not believe this, but I am actually not a huge fan of discussing education outside of my professional life. All too often I find myself in conversations with people who either think the youth of today are going to Hell in a handcart, or that teachers are too soft. Or conversely, I end up listening to people telling me that knowledge doesn’t matter and that we just need to teach children to be creative. Either way I am very bad at the polite but firm disagreement which these encounters require.

Fred had been a teacher in the 1960s and 1970s. I reasoned he had almost certainly been trained in the progressive pedagogies of this period (he once met Piaget it transpired) and was already anticipating where the conversation might go. Meanwhile in 2016, I was drunk on Michael Young, ‘powerful knowledge’; the liberations of ‘rigour’; and busy decrying the ‘soft bigotry of low expectations’ found in many schools obsessed with GCSE grades or ‘21st century skills’. I suspected that our dinner conversation would be one to endure rather than enjoy. As with so many other times in my life when I have been certain of my own rectitude, I was wrong.

Reading none of the books

We helped ourselves to a carvery lunch. Roast beef and all the trimmings. We sat with steaming plates whilst the conversation turned, as expected, to teaching. Fred was interested in my work with new teachers, and I talked a little about what interested me. I spoke especially about empowering young people with knowledge and the role of rigorous history teaching. I cringe a little when I think about it now. He nodded along with interest.

Soon talk turned to Fred’s own time working in a rough and ready Bradford Middle School. The boys were tough and often uninterested in what education had to offer. One class in particular, the ‘remedial class’ had a particularly fearsome reputation for aggressively avoiding learning at all costs. But Fred explained that he reckoned this aggression was not so much a rejection of learning but a fear of it – especially in relation to reading.

“Nothing I could do,” he explained “could persuade these boys to pick up a book and read. And the headmaster just wanted me to buy more books. As if that would solve the problem. It was no good buying more books, they already had them and wouldn’t touch them.”

He went on to explain how he had tried to set up a reading corner at one side of the classroom, but the children wouldn't go near it. They skirted around the books like there was some sort of invisible barrier there. "I realised” he said, “that they didn't hate books, they were scared of them."

My wife and I continued to eat as Fred went into the next part of his tale, occasionally stopping to sample something from his plate. He explained how he removed all the books from the classroom and replaced them with alphabet blocks and word cards he made at home in his workshop. "The head thought I'd gone mad!" He commented, with that same mischievous twinkle, "I took every book out of that class and locked them in cupboards. The only books in there were on my desk. I didn’t even get them to bring their reading books in. What was the point?"

For months, he said, the classroom remained largely book free. Each day he got the boys to do a little practice of the key words and vocabulary, ten minutes here, ten minutes there. And each day he read something to them of his own choosing: anything from football scores to ghost stories, newspapers to novels.

By this point my wife and I had admitted defeat on our own meals and had sat back to peruse the dessert menus. Fred meanwhile returned to eating his roast, slowly making his way through the meal, one bite at a time. As I watched I mused on the story so far. It was much as I expected: lowering expectations and removing challenge in the name of support. My prejudices were confirmed.

As I pondered how I might respond to the tale, the waitress arrived with steaming bowls of sticky toffee pudding. Fred had declined a pudding, opting instead to finish off the last of his main meal. There was a long silence as we began the sickly sweetness of the dessert. Just when it seemed he had forgotten about his story, he began again.

"So do you know what happened with those boys who were scared of reading?" he asked.

"No.” I replied, “How did they get on? "Did you ever get them to read some proper books?"

I wonder if he detected the tone in that question, "proper books"? I hope not. If he did, he didn’t rise to it. Instead, he explained that, three months into his "no books" regime, he began to change his approach. Increasingly he would read quietly whilst the class were working, smiling at a good story, making interested noises. Increasingly the students would ask "What's so funny sir?" Or "What you reading, sir?"

"I knew I had them then you see.” He said, “I was getting them to see that you could enjoy books. I wanted them to know that they were worth reading, worth spending time with."

By this point he was in full flow. The boys in his tale were increasingly enjoying being read to, but he still couldn't get the children to pick up a book themselves. He explained how he tried again to put books in a reading corner, but the same force-field effect seemed to occur.

"Of course," he said, after a mouthful of Yorkshire pudding, "they had to be pushed out of the nest eventually. One day, about May time, I asked one of the boys to get the reading books". At this point he dropped into dialogue taking on the parts of both himself and the boys in the class:

"Here Roberts, go and get that pile of reading books from the store cupboard for me"

"I aren't reading a book, sir!"

"I'm not asking you to, just go and get them and bring them here."

Despite the protestations, Roberts was made to collect the pile of books from the cupboard where they had been locked away for months.

"He carried them back like some sort of nuclear device." Fred chuckled, "Carefully. At arms' length."

After the books were deposited, Fred explained how he picked one up and, with the boy still stood there, waiting to be dismissed, opened it and began reading through. Moments passed with the boy stood and the teacher reading. Fred dropped back into his mock dialogue:

"Bloody hell, sir! I can read some of those words."

"Oh really? Which ones can you read?"

"This one here, and this one."

Fred went on to explain how slowly Roberts began to read the book to him. Meanwhile the rest of the class began to sit up and pay attention.

"By the end of the day," Fred went on, "we'd read that book. The whole class. They'd finally got over their fear of words."

By the time he got to the end of the story, Fred was beaming with pride for his young charges. Even fifty years on the sense of triumph was palpable. I felt it as I lived his story too.

Fred went on to explain how he was able to introduce books back into the class. That the boys began to enjoy reading; to be able to access their lessons; to feel successful in school. What Fred had done was to meet the boys at their point of need and help them to transcend their fears to be successful.

I left the meal feeling very humbled and just a little bit wiser.

I often think about that story when I am working with new teachers. I come back to it because our educational landscape is often painted in black and white. Do this. Don’t do that. The truth is that education is never black and white, and the power of great teaching lives mainly in the messy middle ground.

Early in the PGCE year I do an exercise with trainees where we consider what makes a great teacher. We revisit these ideas throughout the year and amend and trainees change them as they learn and practise their own teaching in the classroom. There are no hard rules for what makes for transformative teaching but whenever I think of a great teacher, I am often thinking of Fred.

Frist, great teachers are curious. If you had been to Fred’s house, nestled away in a quiet cul-de-sac in Idle, just off the Leeds Road, you would have found a life of curiosity. His hallway overflowed with fishing paraphernalia. His living room was filled with homemade toys, which my daughter used to delight in playing with. Next to his chair you would have found shelves of books and homemade contraptions to do this and that. If you had been lucky enough to be invited up the rickety ladder into his attic, you would have found a fully functioning dark room: bottles, trays and developing tanks all still meticulously organised into a careful workflow. When searching for some food recently, one of his children found a packet of old cinefilm in the bottom of the freezer, just awaiting its opportunity to be loaded up and used. Fred could talk on almost any subject. In his time, he worked as a craftsman, joiner, coffin maker, press photographer, middle school teacher, and probably much more. Being curious is not something we often talk about in relation to teacher training but the best teachers I know show this same curiosity in all the work they do. They are curious about their pupils’ experiences. They are curious about what works. They are curious about why some students struggle with this aspect or that. They want to know what is happening and how they can help. And they want to help young people be curious too. Curious about learning. Curious about the world around them. Curiosity is the first step to transformation.

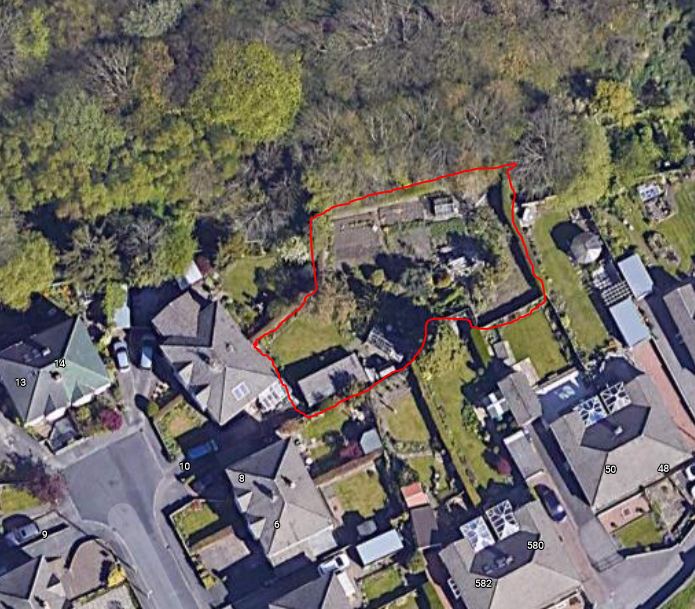

Second, great teachers are methodical; they put in the hard yards and build knowledge and understanding patiently over time. The real joy of Fred’s home was his garden. He told us once that his mother helped him fall in love with gardening at the age of five and this love was nurtured and grew throughout his life. Fred’s modest house was a gateway to the most extraordinary garden. Over the years he purchased little parcels of land from neighbours so that his originally humble back yard eventually stretched in a long, snaking line right across the backs of all the houses on Leeds Road. Patiently, and over many years, he built greenhouses and sheds, weeded and hoed, planted and tended his crops. His garden was a testament to eighty years of gardening knowledge and understanding: a labyrinthine maze of potatoes and carrots, towering sweetcorn, gnarled apple and pear trees, raspberry canes, ripe tomatoes, and juicy strawberries. A garden like this, much like an education, is the work of a lifetime. Whenever I have visited him, he has always encouraged me not to give up on my own fumbling attempts at horticulture. He has never accepted my excuse that I have “black thumbs” and I always received some new advice on when to plant my potatoes, or how to stop my carrots from being stunted.

Finally, the best teachers, just like Fred, understand that all teaching is, at its heart, relational. Unlike many of us who become more irascible and misanthropic the older we get, Fred approached life with a great openness. He loved talking to people. He loved working with children. He was interested in everyone and everything and this meant that, even in his twilight years, he was still meeting new people and forging new friendships. Everything we do as teachers rests on how we form trusting relationships in our classes; how we show patience and understanding; how we help young people to feel successful and like they belong. Fred has this quality in spades. If we hold relationships as foundational to children learning then we will truly have a chance to transform the lives of young people; to open new doors for them in their lives; to help them feel heard and valued. We may never see the results of this work, but it will happen all the same.

But more than all of this, if we hold the three principles above as important in our professional lives, we also become open to shaping and enhancing our wider lives in the process. Fred lived a life which constantly brought him joy through curiosity, which gave him satisfaction through determination, and built relationships which meant that in his final hours he was not alone, but surrounded by the love of his family and many friends.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed