You can find downloadable versions of these resources over on the C19th America blog HERE. If you want to find out more about Chief Joseph, I can highly recommend Elliot West's excellent book: The Last Indian War, or Ken Burns' documentary: The West.

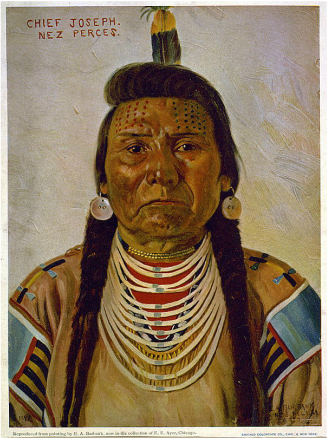

Chief Joseph / E.A. Burbank, 1897. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/97515744/.

Chief Joseph / E.A. Burbank, 1897. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/97515744/. Fight No More Forever

It was late Spring when Chief Joseph looked back over his beloved Wallowa Valley for the last time. The new, green leaves promised a beautiful summer to come. In the past they would have reminded Joseph of the hunting season on the Plains. This time, he saw them differently; fragile and temporary, soon to fall in the stiff Autumn breezes. They reminded him that nothing, not even his own homeland could last forever, and that soon his own people would fall like the leaves in the gale of white settlement.

Land and exploitation

The Nez Perce had historically had good relations with white explorers and settlers, but decades of settlement since the 1840s had strained the relationship as whites came in search of the American Dream. Tensions rose further still when gold was discovered in the 1860s.

In 1863, the government demanded the Nez Perce sign a new treaty, giving away 90% of their lands, including the Wallowa valley. The Nez Perce were divided over the treaty and many refused to move to the reservation. When Joseph became the chief of the Wallowa Nez Perce in 1871, he also refused to give up his ancestors’ vision of a free-ranging life. But this lifestyle was increasingly leading to conflict with white settlers who feared the presence of the Nez Perce, or wanted access to the gold fields.

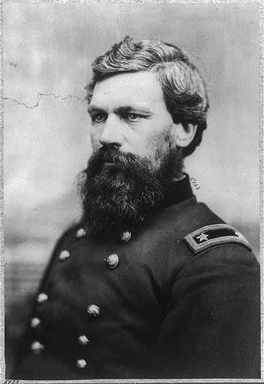

In 1877 Joseph was called to a meeting with the US Army General, Oliver Otis Howard. Howard had already written to his superiors to say “I think it is a great mistake to take from Joseph and his band of Nez Perce Indians that valley...and possibly [should] let these really peaceable Indians have this poor valley for their own.” The government were not convinced. Joseph in turn repeated his stock response, that the land was the home of his people and not his to sell. Howard could almost see the writing on the wall when he came to the meeting with Joseph, but Joseph would not sell the land.

An unwanted conflict

Oliver Otis Howard, Between 1861 and 1865, printed later Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2006681382/.

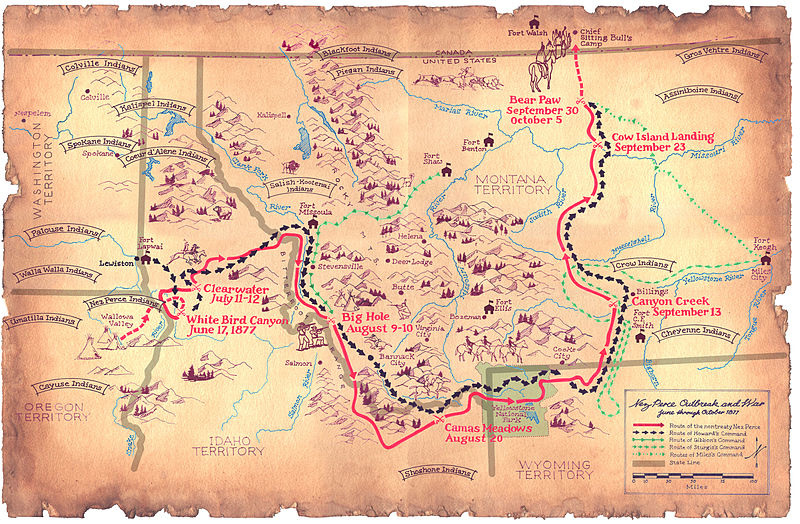

Oliver Otis Howard, Between 1861 and 1865, printed later Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2006681382/. General Howard sent his troops to bring the Joseph’s band to the reservation by force. But Joseph was not willing to give in. Pushed to their limit, his little band of 700 defeated the troops in battle. They then set out onto the Plains in the hope of joining with their allies, the Crow.

The 200 Nez Perce warriors defeated the US army in numerous battles. But on the night of 8th August, Commander John Gibbon caught up with them at a spot known as the Big Hole. Gibbon ordered a dawn attack and, just as at Sand Creek, Indians were slaughtered before they had time to get out of their blankets. Women and children were cut down as the mountain howitzers shelled the camp. In all, over 100 Nez Perce were killed before they managed to escape.

The slaughter at the Big Hole was a huge blow for the Nez Perce, but not as great as the realisation that their former allies, the Crow were now scouting for the United States army. The betrayal forced Joseph to reassess his vision of the Nez Perce’s future in the United States. He turned his people north towards Canada, hoping he might join Sitting Bull and the remaining Sioux there. Their journey took them through the new, Yellowstone National Park. The Park was the first set up to preserve the western wilderness; although this was a vision of wilderness cleansed of Indians. Startled tourists gawped at the ragged band trooping through their playground. A handful of sightseers were even killed by some angry Nez Perce youths, sparking national outrage and panic in the newspapers.

Fight no more

By September, the Nez Perce had travelled over 1,500 miles and fought seventeen battles against the US army (see map on p75). Forty miles from the Canadian border, they stopped to rest. Joseph urged them to move on, but many of the old people and children were too tired. The stop proved to be fatal. The new railroads and telegraph wires which brought opportunities to so many whites, were already bringing Colonel Miles and his troops, thousands of miles across the country to intercept the Nez Perce. Railroads allowed the government to exercise its power in this way all over the West. They were like a barbed wire fence, corralling the Nez Perce in, stopping their escape.

On 30th September, 1877, as the first snows of winter began to fall, Miles made a surprise attack. For five days, the army kept the Nez Perce pinned down whilst Howard’s troops caught up. A handful of Indians managed to slip away and escape to Canada, but Sitting Bull would not send aid. Finally, Joseph rode out to meet the man who had pursued him all those months, Oliver Howard.

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are all killed… The old men are all dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no food. No one knows where they are....I want to have time to look for my children…Maybe I shall find them among the dead…I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.

Soon, Joseph was writing to the man he now considered his closest friend, Oliver Howard, hoping for a chance to return to the Wallowa Valley. Eventually, in 1885, permission was granted for the majority of the Nez Perce to return west if they converted to Christianity and settled on a reservation in Idaho or Washington. Of the 700 Nez Perce who left in 1877, only 268 survived to return. Joseph died on the Colville reservation, Washington in 1904, hundreds of miles from his beloved Wallowa Valley. His doctor recorded the cause of death as ‘a broken heart.’

Despite all the visions of new lives in Wallowa country, two hundred years later, a mere 6,821 people live in Wallowa County.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed