In my previous blog I looked at the ways in which the marking of examinations in England is particularly problematic in subjects like History and English. For a full review of this, you may like to read Ofqual’s blog and report on the subject. Today I want to deal with the question of what action the educational establishment might take.

GCSE and A-Level examinations are still being held up vital to the education system. The impetus has been to seek to cement their place as the “gold standard” both nationally and internationally. If we want this to be true in reality, I wonder if we need a more fundamental rethink of what examinations (especially GCSE examinations) are for and therefore what they might be in an educational landscape which is vastly different from that of the late 1980s when GCSEs were first introduced.

What are GCSE examinations for?

The seemingly simple question of the purpose of GCSE examinations is actually very complex indeed. But of course, as with all assessment, validity is heavily connected to the inferences one wants to draw from an exam (Wiliam, 2014). The range of inferences which are suggested as valid from a set of GCSE examinations are extremely diverse:

- GCSE grades might tell us how well a student has done in a subject compared to others who studied the same subject

- Ofsted have used GCSE grades to determine school impact and educational quality

- Employers have sought to use GCSE grades as a broad indicator of a student’s ability to communicate effectively, or perform core tasks. Children are often told directly that good GCSE grades tell potential employers that they are good candidates too.

- School leaders have used GCSE results to draw inferences about the effectiveness of their departments and teachers.

- FE and Sixth Form Colleges seek to use GCSE grades as a measure of potential for a student to engage in further study

- The DfE use GCSE English and Maths grades (C+) as a partial determiner of a candidate’s suitability to become a teacher.

- Some universities (notably Durham) have even used GCSE grades as a means of distinguishing between groups of students who all have a clean sweep of “A” grades at A-Level.

I could go on, but you get the picture I think. The real question is whether the current system of GCSE examination can meet these purposes. I don’t have the space for a long analysis here, but it is fair to say that Ofsted have already begun to recognise the limits of GCSE grades as the sole measure of educational quality. Equally, any school leader worth their salt knows that GCSE results are only ever a partial picture of a teacher’s effectiveness. Employers frequently complain that GCSE grades don’t give them any useful information about a young employee’s ability to communicate correctly in a letter or email, or to complete financial calculations. Universities make similar complaints at A-Level. Similarly, the DfE themselves require trainee teachers to take additional maths and literacy tests to confirm their abilities – the GCSE is not trusted alone. Pupils also quickly find that their GCSE grades might get them a foot in the door, but they are far from the ticket to wealth and happiness they were promised.

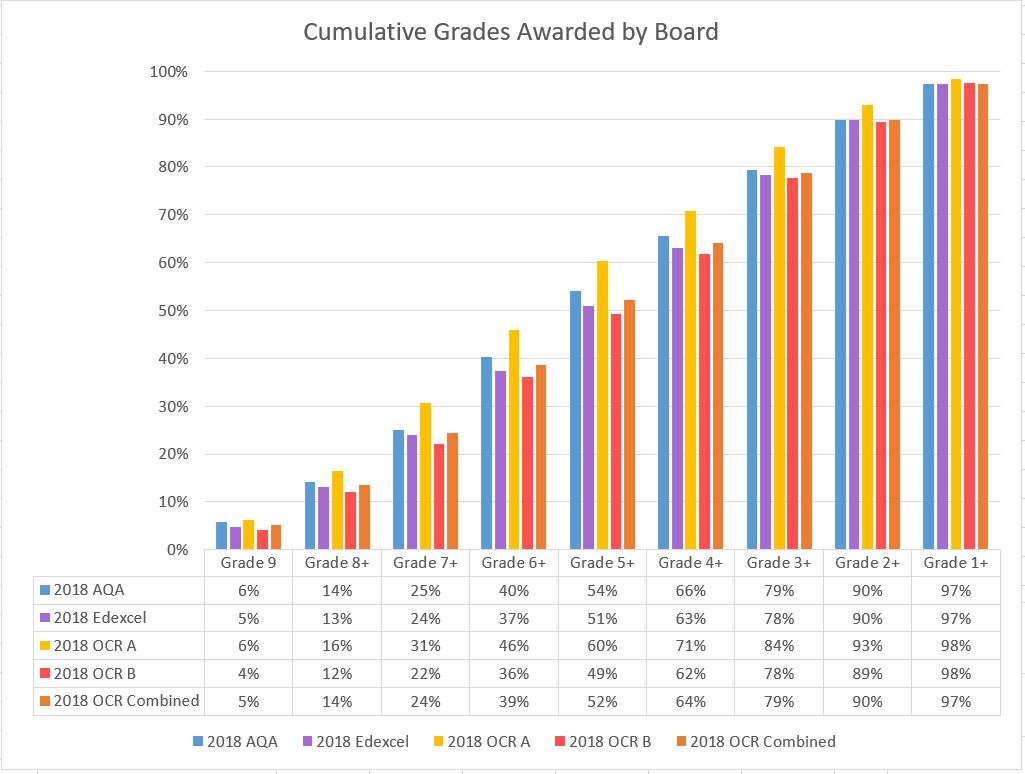

If we were to look at the function GCSE examinations really perform it is this: They show were a student sits in a rank order with their peers in a particular exam board’s interpretation of a subject. A pupil who gets a grade 7 in history therefore can say that they are in the top 25% of students who sat the OCR History B paper in 2018 (or at best the top 25% of students who sat a history paper in 2018). Can we draw some useful inferences from this? Maybe, but they will not extend well to the multitude of purposes outlined above, and this is all thrown in the air anyway when we consider that there is a 4% chance this grade is too generous or lenient by two grades and a 45% chance that it is a single grade out (i.e they might be in the top 10% , or just the top 40%) (Ofqual, 2018).

- We could suggest whether students had met a set of agreed upon baseline standards in various subjects, and therefore draw inferences about their readiness for the next stage of their education and training

- We could use examinations as a broad measure of how well the curriculum had been delivered in a school.

Comparative judgement

I am not going to explore CJ in great depth here as I know much has already been written on the subject. However, the effective idea is that, rather than trying to fit essays into a mark scheme, we instead place them into a rank order. The big difference with CJ however is that no mark is ever entered, we simply decide the order by comparing two essays – a big data system then creates the rank order by using other markers’ interpretations.

CJ has many potential benefits if our end goal is to create a ranked order of candidates (as GCSE and A Level currently do). However, there are issues if this is not our goal. I also have some worries that without the requisite number of specialist markers, each with a good knowledge of the topic being assessed and a good understanding of how it was taught, then a system like CJ will end up prioritising generic features such as structure, or the inclusion of a conclusion. That is to say: if I had 4 markers (two specialists and two non specialists), the specialists might look for niche features such as the nature of the causal explanation and the particular language of cause deployed, as well as generic features; the other two might only look for the generic features. This would then weight the generic features more in the ranking. This is not insurmountable, but it is an issue! As an example of this, I wonder which KS3 essay (below) you think is better. I would argue that non-specialists would choose one and Norman history specialists the other.

We might also deal with grading issues by doing away with them altogether. In many countries (including large parts of the US and Canada), students do not finish secondary school with a set of grades, but with a certificate of matriculation to confirm they completed their courses successfully. This removes the pressure of examination outcomes and means schools focus more on ensuring the matriculation standard (as defined nationally or indeed locally) is met, rather than on trying to jump hoops to reach particular grades. There might even be a case to say that students could be offered an opportunity to take extra-credit assessments to pass at a meritorious, rather than a standard level. Having only three possible outcomes would significantly reduce the possibilities for error.

Ten years ago, this idea might have seemed farfetched, but the Primary assessment system has already moved in this direction by having a standard for the end of Year 6 which pupils can either be meeting, above, or below. Given that pupils now must stay on in education or training beyond 16, this kind of system might be a much better bet. This might be further strengthened if a focus on grammar was also brought into secondary schools, relieving the internal tensions in English where focus is split between creative types of writing, literary appreciation, rhetoric, and other core areas. Having said that, the ever-wise Sally Thorne has informed me that she had listened to someone talk about the “tyranny of matriculation” in the 1920s and 1930s this week, so maybe this is not quite as golden as I would like to believe.

Improving specifications in problem subjects

One thing which came out of the Ofqual report very clearly was that issues of examination were much more pronounced in some subjects than others. Where questions had definitive answers and where questions were shorter, as in Maths, the rates of agreement were extremely high. In fact, reliability remained quite high even with longer questions. This, I would hold, is because the content being tested is largely fixed and agreed upon. We could argue then that a system of national examination for Maths, and other subjects where there is broad agreement on desirable core knowledge is acceptable.

As a real-world example consider the driving test. This has both an examined and a practical element, but there is good agreement on what new drivers should do to be safe drivers in the longer run so the test broadly works (I appreciate there are shortcomings too). Now let’s imagine a different case. What if we wanted to determine whether someone was a good artist? This would be nigh on impossible as so many other factors would come into play – the range of knowledge which could potentially be required would be almost limitless. We could of course reduce the variability and say that a good artist could be determined as those who can accurately reproduce a copy of da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa”, but this would, I imagine, cease to be art. (I should briefly note that of course in subjects like art, the need for a very different form of assessment is already recognised and in place)

To come back to school subjects then, the only way to ensure that English Literature, or History could be marked as accurately as Maths at a national level would be to reduce the instances of open response questions and set out a more definitive curriculum. This approach is loaded with problems and is certainly not one which Ofqual seems to favour. How does one even define what it is desirable to know in History for example? And would it be possible to boil this down to a list of testable facts? This has certainly been tried in many US states. Indeed in Florida there was an attempt to define history as “factual, not constructed”. History, the legislature argued should be “viewed as knowable, teachable, and testable, and shall be defined as the creation of a new nation based largely on the universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence.” Of course all of this is somewhat ahistorical as illustrated in this fascinating report by the Fordham Institute (Stern & Stern, 2011).

Improving examinations in problem subjects

Without a list of definitive knowledge, exam boards are forced to create generic statements in their mark schemes. In some ways these give broad guidance: “some analysis” versus “consistently analytical” or “a sophisticated understanding” vs “sustained and convincing” for example. However, these terms always need redefining in relation to specific questions post-exam. In the worst scenarios, boards resort to performative shortcuts such as “the student identifies two reasons” or “the student explains three reasons”. This in turn leads to the kind of generic hoop jumping which skews the teaching of a subject.

A shift to a system of matriculation might reduce some of these problems, but would not remove them. Instead, exam boards might take the plunge and start trialling assessments on students before the final exams. This does carry risks, but means that at least live testing would have happened on such high stakes papers beforehand. Many other countries do this. Not doing so feels like testing out a new plane with a full compliment of passengers, rather than in a dummy flight with no-one on board! Another option would be for exam boards to return to a system whereby more of a subject is assessed by teachers in school (as in art) and moderated by the board. This could include teachers setting their own questions within board parameters and with verification; or might involve teachers being given set questions at the beginning of the course, some of which might be sampled on this final exam (this is similar to the way in which coursework operated). Teachers would also then be tasked with creating specific question mark schemes connecting the broad bands and the specific knowledge delivered in the course. This would mean that teachers would have a better grasp of the specific knowledge they needed to teach and would also be able to reward their students for applying this appropriately in relation to questions. Of course, this in turn comes with a whole new raft of issues if we want to maintain the accuracy and reliability of those judgements of student and school performance.

Finding gold?

The search for a new gold standard of examination does not seem to be a case of simple modification. Instead the case might be made that subjects where there is little agreement on content need a more radical solution to examination. I will be writing more on this in my final blog.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed