A few days ago, Ofqual published an interesting blog looking at the state of the examinations system. This was based on an earlier report exploring the reliability of marking in reformed qualifications. Tucked away at the end of this blog was the startling claim that in History and English, the probability of markers agreeing with their principal examiner on a final grade was only just over 55%.

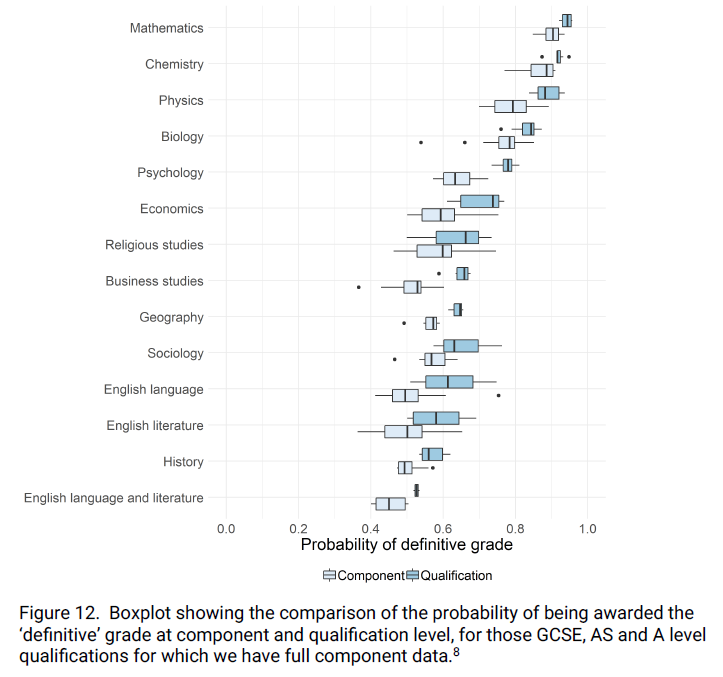

The research conducted by Ofqual investigated the accuracy marking by looking at over 16 million "marking instances" at GCSE, AS and A Level. The researchers looked at the extent to which markers’ marks deviated from seeded examples assessed by principal and senior examiners. The mark given by the senior examiner on an item was termed the “definitive mark.” The accuracy of the other markers was established by comparing their marks to this “definitive mark.” For instance, it was found that the probability that markers in maths would agree with the “definitive mark” of the senior examiners was around 94% on average. Pretty good. They also went on to calculate the extent to which markers were likely to agree with the “definitive grade” awarded by the principal examiners (by calculation) based on a full question set. Again, this was discussed in terms of the probability of agreement. This was also high for Maths. However, as noted, in History and English, the levels of agreement on grades fell below 60%.

When Michael Gove set about his reforms of the exam system in 2011, there was a drive to make both GCSE and A Level comparable with the “the world’s most rigorous”. Much was made of the processes for making the system of GCSE and A Level examination more demanding to inspire more confidence from the business and university sectors which seemed to have lost faith in them. Out went coursework and in came longer and more content heavy exams. There was a sense of returning GCSE and A Level examinations to their status as the "gold standard" of assessment. The research conducted by Ofqual seems suggest that examinations are a long way from such a standard. Indeed, it raises the question of whether or not national examinations have never really been the gold standard of assessment they have been purported to be. Have we been living in a gilded age of national examinations? The answer is complex.

Before I launch into this, I should also note that I understand the process of examining is a difficult one and that I have no doubt those involved in the examinations system have the best interests of students at heart. I also don’t want to undermine the efforts of those students who have worked hard for such exams. That said, there were some fairly significant findings in the Ofqual research which need further thought.

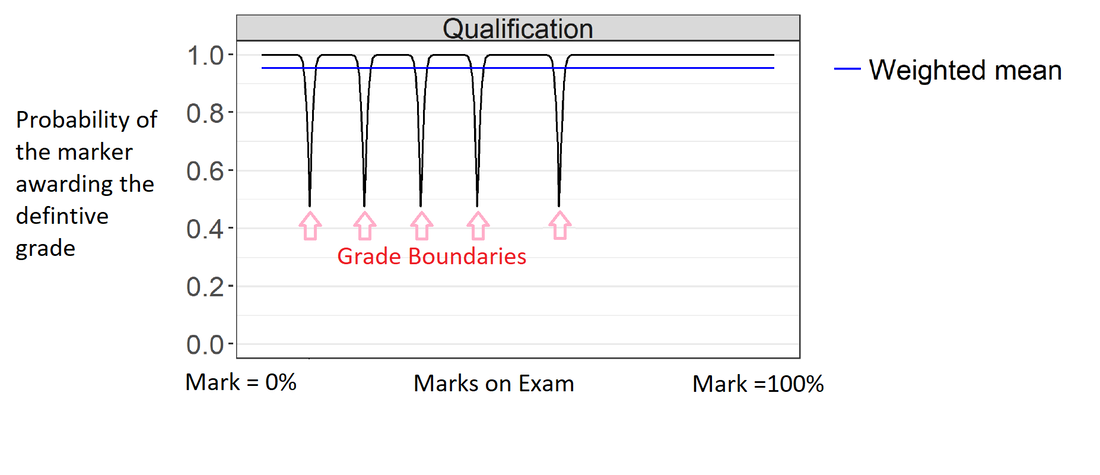

As noted, the Maths GCSE gives a good example of how marking should operate when it is really effective and rigorous. The chart below is taken from the Ofqual report (annotated by me) and gives a nice illustration of something approaching a “gold standard”. Here the probability of the student (at almost any point on the mark range represented on the x axis) receiving the “definitive grade” is effectively 100% (seen on the y axis). This represents theoretical complete agreement between the marker and principal examiner. The only exceptions to this are near grade boundaries where the small variations in marking standardisation mean that the probability of getting the grade right reduces to just under 50%. This is exactly what one would expect. Once the boundary is cleared, the agreement rate returns quickly to maximum.

Something more base...

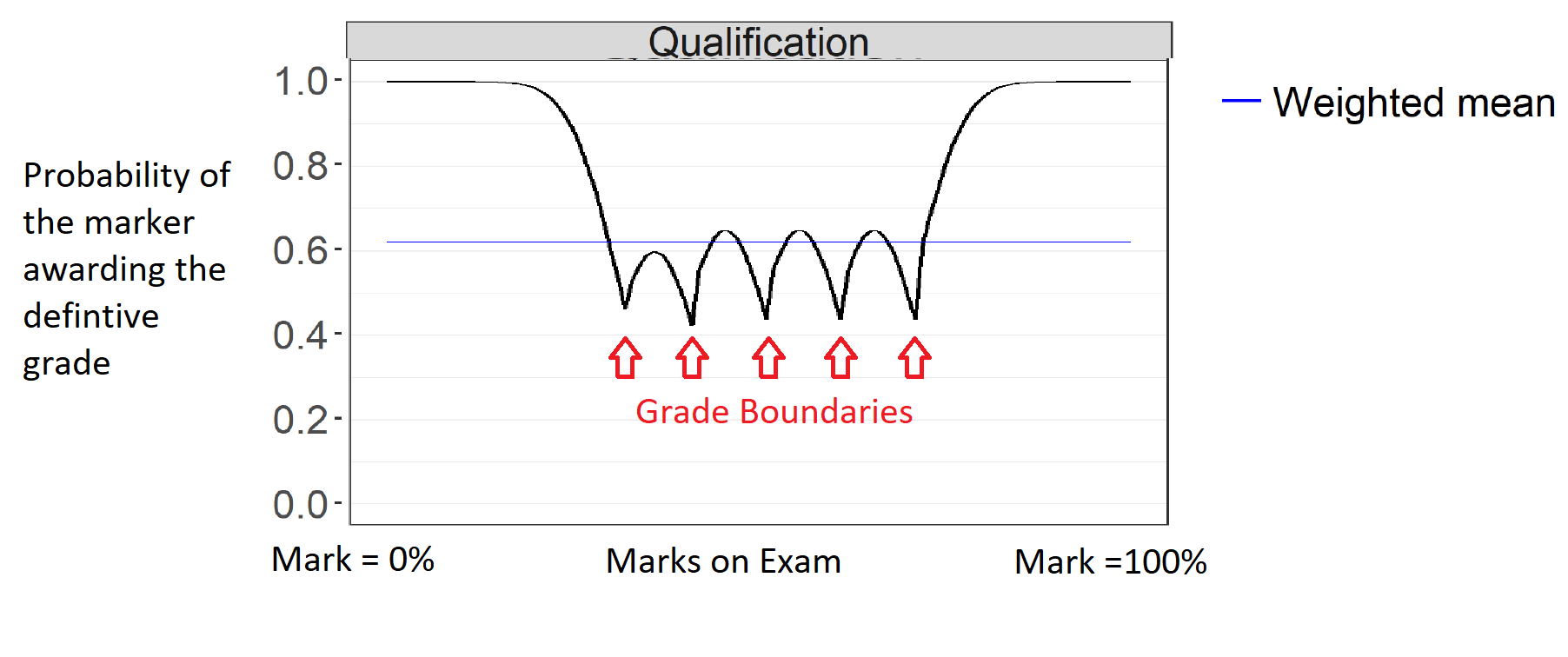

If we move away from Maths and turn to AS History however, we see a starkly different picture. Apart from outlying examples at the top and bottom of the mark range, the bulk of the assessment sees limited agreement between the markers and the principal examiners. The probability of markers getting the same “definitive grade” as the senior examiners sits at just 61% on average, seldom rising much above 62% even in the middle of a grade. There is also a long tail off towards the grade boundaries. In essence then the reliability of such marking for determining grades has to be questioned and explained. This is something Ofqual attempt to some extent in the rest of the report.

A larger degree of difference may come from the fact that there is no definitive list of what should be in an essay question. A student answering the prompt: "To what extent were military reverses responsible for the downfall of Nicholas II?" would likely address military reverses, but could choose from a wide array of other factors, few of which will have been directly specified by the exam board ("opposition and the collapse of autocracy"). Equally there is not even a definitive list of which military reverses a student should discuss.This is before we factor in the variances of how teachers might have interpreted the specification item itself - should the focus be on all opposition? or on the connections between the opposition and the collapse? Or the nature of the collapse and its aftermath? And so on. Because most teachers are not party to the discussions which happen during specification creation, they are almost always guessing what they might best teach and therefore students may answer similar questions in very different ways. In short, the nature of history as a subject of great breadth makes the job of the marker extremely difficult. And of course markers do not need to have a specialism in the topic they are marking - another level of difficulty.

History is not alone here either. The probability of agreement on a definitive grade sat between 60% and 70% for RE, Geography, Computer Science, Business Studies, and Sociology. Meanwhile in English and History saw agreement rates as low as between 50% and 60%.

The big question is does any of this matter. I for one think it does. My first port of call for this is Terry Haydn’s excellent work on assessment in which he noted that the first principle of testing should be “first do no harm”. We have already seen the disproportionate impact of examinations on curriculum (something Ofsted is finally tackling) and increasingly on students’ mental health. The fact that the marking system is so deeply flawed does not add great confidence. Indeed, I spent many years as a teacher fighting to have the efforts of history students properly recognised in this system. A quick check back reveals that of the 43 scripts I sent for re-marking between 2011 and 2013: 22 increased their mark (by an average of 10 marks - a grade and a bit); none went down; five went up by 15 marks; and two went up over 20 marks (3 grades). None of these were transposition errors.

What worries me more is that Ofqual’s summary of the findings suggests little appetite for real change and an under-appreciation of the scale of the problem. For instance, the report noted that in all subjects apart from English, Sociology, Geography and History, the chance of students receiving the “definitive grade” +/-1 was 100%. However, this is still a large variation when students’ futures and school reputations rest on the accuracy of such grading. Worse still, for English and History, the chance of students receiving the “definitive grade” +/-1 only came out at around 96%. This implies that 4% of students were 2 grades or more from the definitive grade. This could mean a child in GCSE English gaining a Grade 3 rather than a Grade 5. Of course, Ofqual also noted that there is a system to review marks in place. This is true, but at over £40 a review, a student wishing to confirm their marks in the four or five problematic subjects noted would be shelling out £200 on results day!

Ofqual’s response also did much to downplay the issues. For example, Ofqual note in the report that variations in marker accuracy have remained fairly similar over the last five years. To me this is cold comfort and just reinforces that the system has been failing in many regards for a long time. Ofqual also note that we sit broadly in line with other countries when comparing the accuracy with which “6 mark” questions are graded. Again, there is not a lot of solace here. Being comparably problematic feels a little complacent at best. And of course, other jurisdictions do not necessarily place such a high focus on graded outcomes at 16 and 18 for either pupils or schools, so it is not really comparing like with like.

The only radical suggestion made for change was that it might be possible to do away with the reporting of grades and replace this with reporting a mark and confidence interval. This would certainly provide more information, but I am not sure it would be especially helpful for a university to know that there was 60% certainty that a pupil had scored 65% on their history exams. Indeed, most of the hope for change rested on a single suggestion that there might be “state-of-the-art techniques and training” brought in to support standardisation in essay-based subjects. Whilst this all sound very impressive, to me it smacks somewhat of the high-tech Irish border solution we keep being promised by the Brexit lobby: it only exists in fevered imaginations or fiction.

For the last 30 years and more, national examinations have been held up as an entirely vital, dispassionate, and fair assessment of pupils’ abilities, as well as of schools. Whilst there might be some case for arguing such in Maths, I am not sure we can say the same in History or English. The exam system at its core is rusty base metal rather than gold. All Gove’s reforms have seemingly done is add another glittery coating to keep up the pretence that it is otherwise.

The nettle which might need to be grasped is that our system of assessments needs more fundamental change. This is something I hope to discuss further in my next blog.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed