- Content from 3 different periods of time: Medieval, Early Modern, and Modern

- A breadth study which covers all three of these periods

- A period study which tells an unfolding narrative

- A British depth study which can come from any period

- A World depth study which cannot come from the same period as the British one

- A study of the historic environment

One of the most important tasks for history departments over the next few months will be narrowing down and choosing which specification best fits your students, expertise, interests and (sadly) resources (again, I might make this a future blog). Once you have decided on a suitable route, you can then think about mapping out how you will cover each of the units in the 10-12 weeks allocated by the new specification materials. This is also a good way to test specifications as some certainly have an awful lot of content to cover! I have already written about the process of unit planning for the new A Level HERE and HERE, highlighting the importance of excellent subject knowledge in planning meaningful units. I will not repeat that, but if you are considering issues of planning for GCSE then these posts would be a good starting point.

The one worry I hear a lot with the revised GCSE, is that it demands a lot of content knowledge and may be inaccessible for weaker students. I therefore want to spend the rest of this post exploring these claims and considering how we might respond as history teachers who want every child to be able to access and enjoy really great history.

Let me get this out of the way to start. I don't think that the new GCSE is any more inaccessible than the old one. HOWEVER, I do think the new GCSE puts greater demands on teachers to ensure that students CAN access the content AND are able to remember it for examination. In the best cases (OCR B springs to mind), the new forms of assessment in the GCSE should mean much less drilling children to answer particular question types, allowing us to focus much more on teaching them the interesting bit, the history.

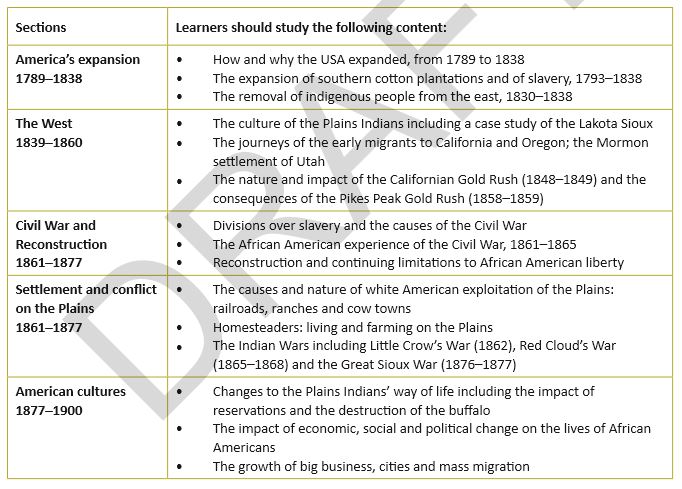

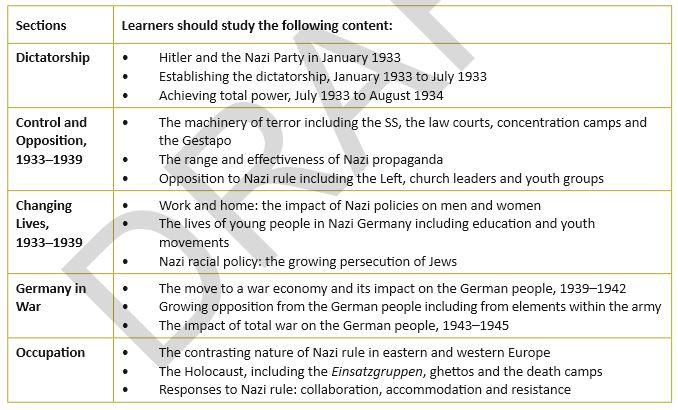

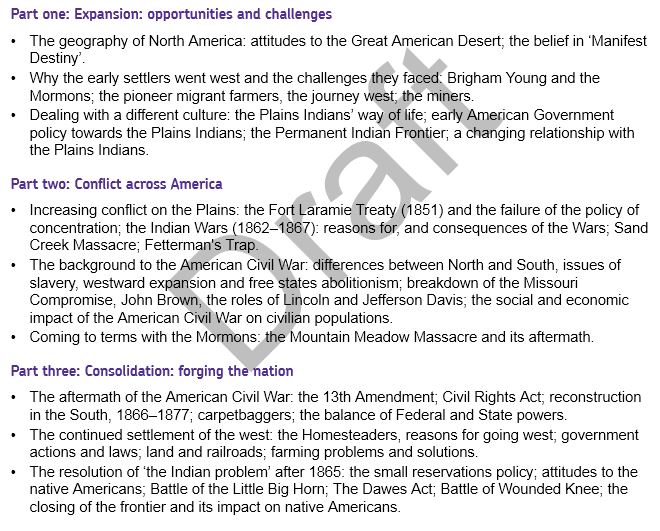

Never-the-less, content coverage is naturally a concern. I have included two extracts of units from the OCR B specification below. The first is a period study (note it has much broader content) and the second is a depth study. Remember though, that each of these needs to be taught in around 12 weeks. Assuming you get 5 hours a fortnight, that means 2 lessons per bullet point! The timing is very tight!

Context and accessibility

This brings me to my main theme: context as a tool for making the history accessible. In other words, adding complexity to make it easier. There has been a tendency over the last two decades for some groups to suggest that making complex subjects like history accessible to weaker students, means simplifying them and breaking them down into smaller, easier chunks. There seems to be a good logical argument for this approach. Why overload students with a vast amount of extraneous detail which they will not need for the exam? If one needs to explain why Weimar recovered under Stresemann, 1925-1929, then why spend a load of time exploring censorship in imperial Germany, the Manifesto of the Bauhaus movement, the controversial music of Schoenberg, the 1920s in America, the works of Friedrich Nietzsche and their influence on Hitler, or the mad genius of Fritz Lang? Surely it would be better to give the students a list of reasons why Weimar recovered and move on: the stabilisation of the mark; the recovery of industry; the growth of art and culture; Stresemann's deals with the USA (but with caveats) etc. etc. The problem with this approach is that students never really appreciate why this was a recovery, or who such a recovery was angering. In short, students have a surface grasp of the relevant content, but no real understanding of the development of the society underneath. Such a surface grasp actually hinders real and lasting understanding. I have covered the importance of adding complexity in a previous post on revision HERE, but the point is hugely important to how we teach. Seemingly disconnected facts are hard for our brain to process.

Let's take another example, shamelessly stolen from one of Christine Counsell's sessions at the SHP conference a few years ago. Below are two pieces of text. Spend 2 minutes reading over the first piece, then cover it up and see how much of it you can write down. Then do the same for the second. Ready?....

Courts. Paper. King. Equals. Jury. Success. Meadow. Safe. Angry. Rights. Seal. Fight. Gathered. Win. Free. Fines

"At Runnymede, at Runnymede,

Your rights were won at Runnymede!

No freeman shall be fined or bound,

Or dispossessed of freehold ground,

Except by lawful judgment found

And passed upon him by his peers.

Forget not, after all these years,

The Charter Signed at Runnymede."

So let's consider the practical applications of this approach to teaching the new GCSE. As we saw earlier, the GCSE specifications are significant, as much for what they neglect to specify, as what they do. Let's take the example from the OCR USA specification. The first section states that students need to understand:

- How and why the USA expanded, from 1789 to 1838

- The expansion of southern cotton plantations and of slavery, 1793–1838

- The removal of indigenous people from the east, 1830–1838

In order to do this effectively we need to consider what contextual knowledge and what understanding of mentalities we will need to develop. First students will need to appreciate the nature of American government and the situation America was in in 1789: a loose grouping of states with conflicting views over how much power the central government should have over them. Second students will need to understand the drivers of cotton expansion: the desire for profits in international cotton trading; the attitudes of white settlers who believed they had conquest rights to a whole nation; the fear that a lack of expansion would leave room for other Europeans to expand their colonies; and the notion that neither blacks not Indians were part of the American project. Finally, students will need some sense of the historic relationship between Indians and the American nation: the fact that Indians had allied with the British in the 1770s; and the notion that Indians did not act as a unified group of people. None of this specifically addresses the content requirements, but all of it is vital if students are to make sense of what happened.

The real challenge is making that context accessible to all. There are a huge number of ways to do this, so I only aim to outline a few here:

- Using primary documents and images to get into the mentalities of people in the period. The Declaration of Independence for example actually uses the phrase "merciless Indian Savages" to describe the native population, and goes on to say "whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions." This helps us build a pretty clear picture of white mentalities when it comes to relations with Indians in the 1780s. Add into that the statement by Andrew Jackson in 1835 that, "All preceding experiments for the improvement of the Indians have failed. It seems now to be an established fact they cannot live in contact with a civilized community and prosper." or the images of Indians fighting Daniel Boone in popular children's books, and one can begin to gauge how little these attitudes changes in those first 50 years.

- Using stories and narratives. This is what makes history brilliant, the genuine connections we can get students to feel with the people they are studying. A whole host of detail on how the Indians were treated when they were removed from their lands in the 1830s is important for looking at the impact of Indian Removal, but to hear a 14 year old boy tell the story of his removal, and to finish on the words below, makes the connection between the attitudes and the individual realities that much more visceral.

"I know what it is to hate. I hate those white soldiers who took us from our home. I hate the soldiers who make us keep walking through the snow and ice toward this new home that none of us ever wanted. I hate the people who killed my father and mother. I hate the white people who lined the roads in their woollen clothes that kept them warm, watching us pass. None of those white people are here to say they are sorry that I am alone. None of them care about me or my people. All they ever saw was the colour of our skin. All I see is the colour of theirs and I hate them.” - Looking for patterns is also a key way of helping weaker students grasp the narratives and contextual details. If there are repeating themes or drivers, make the most of these. For example, much of the 1789-1838 period in America can be linked to movement, to feet moving from one place to another. Slaves were force marched to the South, feet walked for hundreds of miles in chains so that cotton investors might make huge profits. Similarly, settlers' feet created paths into new territories west and south in an attempt to seize new lands for themselves and their families; their feet ran ahead of the government. Finally, the feet of Indians were forced to march to new lands when their ways of life fell out of step with the United States. By searching for and using recurring themes such as these, we can help students remember the stories as they have something to hang them on.

- Finally reading the history yourself is crucial to achieving all of the above. Not long ago I was struggling to find a way to unify the period of the West 1839-1860. It was reading Elliot West's Contested Plains which brought the idea of seeing the growth of America in the period as one of competing visions: Indians visions of the Plains as a way of sustaining a horse-centred life; Mormon visions of religious freedom; gold miners’ visions of riches, and so on. Equally, when looking at slavery, Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told gave me real slave experiences to put at the centre of my teaching. Baptist also allowed me to see how capitalism actually underpinned much of American development, even in the seemingly archaic South. Rich Kennett has also been doing some amazing work considering how we might develop a sense of period, over at radicalhistory.co.uk.

As ever, all comments and thoughts on this post are appreciated.

Mr F

RSS Feed

RSS Feed