Linear progression models have dominated the way we talk about progression in history for many years now. Once upon a time, they were an odd perversion created by the mis-use of National Curriculum levels, but now they are absolutely everywhere, infiltrating everything from A Level to GCSE.

Linear progression models attempt to create a series of steps which pupils must climb in order to improve at a subject. In maths for example, pupils might begin to understand the concept of angles and their relationships to straight lines by looking at how angles on a straight line add up to 360 degrees, then moving on to deal with angles on parallel lines, and so on. In maths this has the potential to work because there are clear steps for pupils to take to improve in their knowledge of angles and lines.

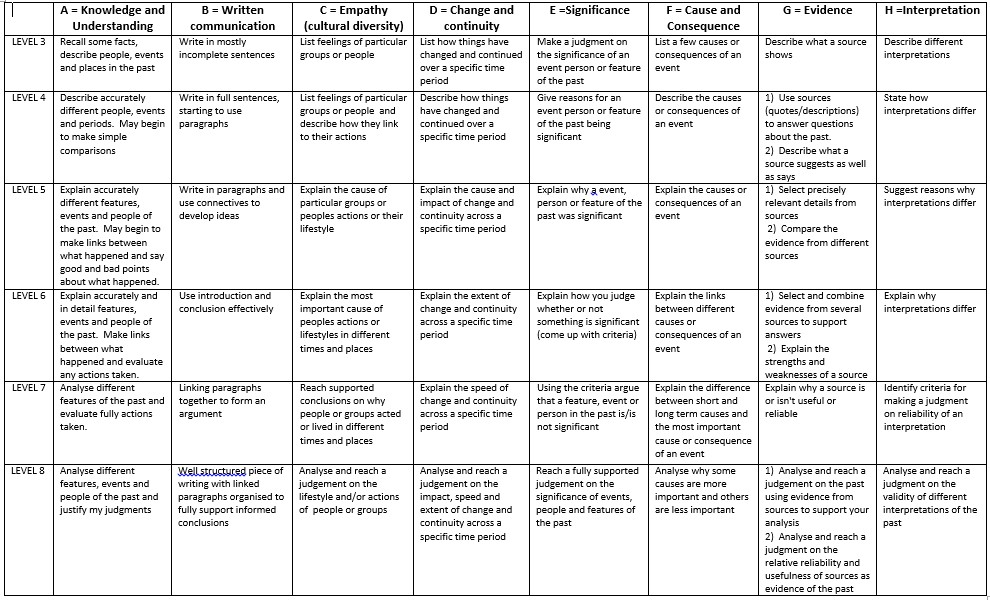

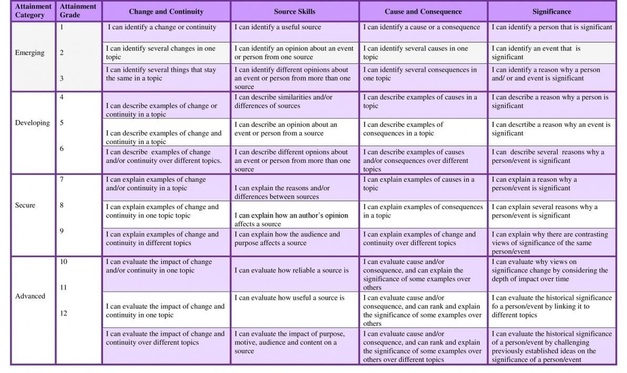

In history the situation is quite different. Linear progression models, such as those used by many schools up until the abolition of the National Curriculum level descriptors, were generally based on the idea that students could improve through a focus on their second-order understanding, rather than knowledge; that is to say, the ways in which we understand history, for example through our understanding of significance, cause, or change. See the example below:

The example below is a school-adapted progression model taken from the parts of the 2011 National Curriculum levels for history which focused on historical interpretations.

- I can explain that the past can be represented or interpreted in different ways.

- I can suggest reasons for different interpretations of events, people and changes

- I can describe and explain different historical interpretations of events, people and changes

- I can explain how and why different historical interpretations have been produced

- I am able to make clear and precise judgements about the value or importance of evidence to identify interpretations.

- I explore historical interpretations to construct convincing and substantiated arguments and evaluations based on them

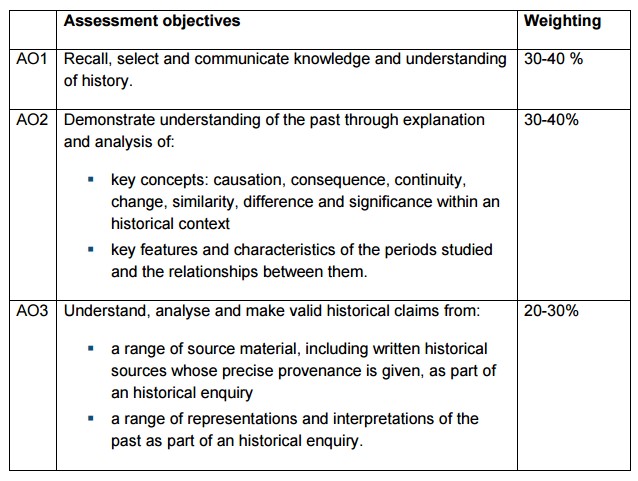

A final issue is that these steps offer no connection to historical knowledge and therefore suggest that historical thinking can be mastered in isolation from content. In the model above, second-order concepts such as historical interpretations are seen as generic “skills” with value in their own right, rather than as ways of understanding historical knowledge. As a result of this view some schools have to adopted an “anything goes” approach to history teaching, seeing historical content as a vehicle for developing “skills” and thereby losing the idea that students might make progress in their understanding of substantive knowledge as well. To an extent this was what the curriculum reforms of 2014 were responding to. The linear, skill-focused progression model was therefore the death knell of many a coherent and well-designed history curriculum. By dismissing the important role of knowledge in second-order development, teachers were free (and still are) to pick and choose what they covered, sometimes with little thought for how this knowledge might contribute (or not) to students’ understanding of history across key stages.

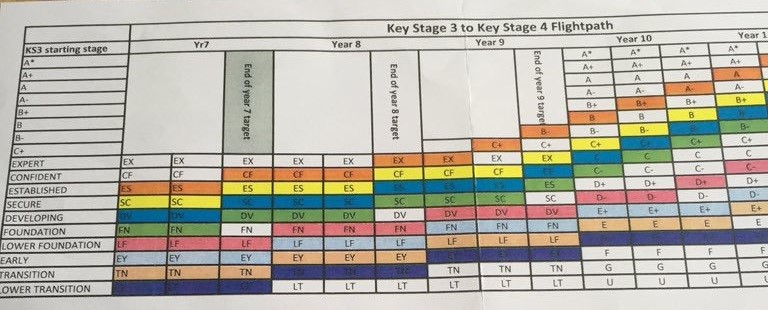

To compound the issue further, this approach has also found its way into GCSE study. Ten years ago it was generally accepted that if a child got a B grade in their Year 10 assessment on the outbreak of the First World War, it showed that they had a B grade understanding of the outbreak of the First World War (with some connected examination skill issues). If they moved on and got a B grade in their assessment on the development of the Cold War, we would have celebrated that they had maintained their conceptual understanding whilst assimilating new content – they would have made progress! Increasingly however, pupils are expected to progress in grade terms across their GCSE study. Indeed, some schools have gone as far as to subdivide their grades into B1, B2 and B3 (or similar). Therefore the pupil in the example above would have been seen as making NO PROGRESS because their overall grade did not increase. Such a view of progress at GCSE completely ignores their progression in substantive knowledge and focuses students instead on the false prophet of “exam skills”. Of course, a mere moment’s thought would lead most to realise that starting a pupil on a Grade E and moving them to a Grade C over 2 years would actually involve teaching them to scramble from one level of misunderstanding to another. This situation will only get worse as we move to a system where the exam grades are numbers and therefore imply a linear progression. There are many implications here for pupil wellbeing, but that is another blog I fear.

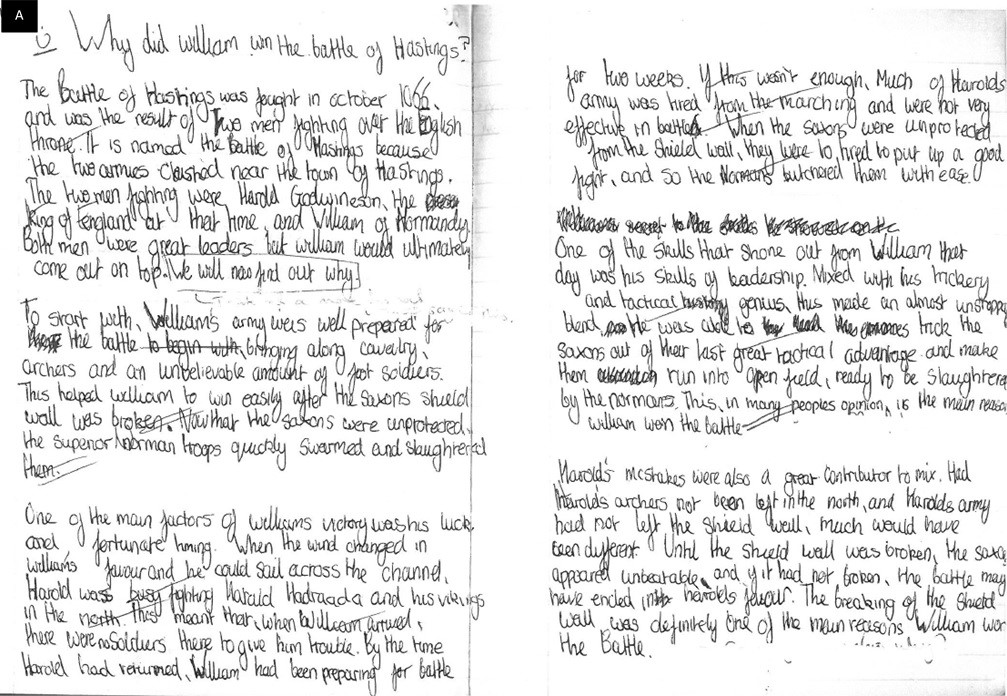

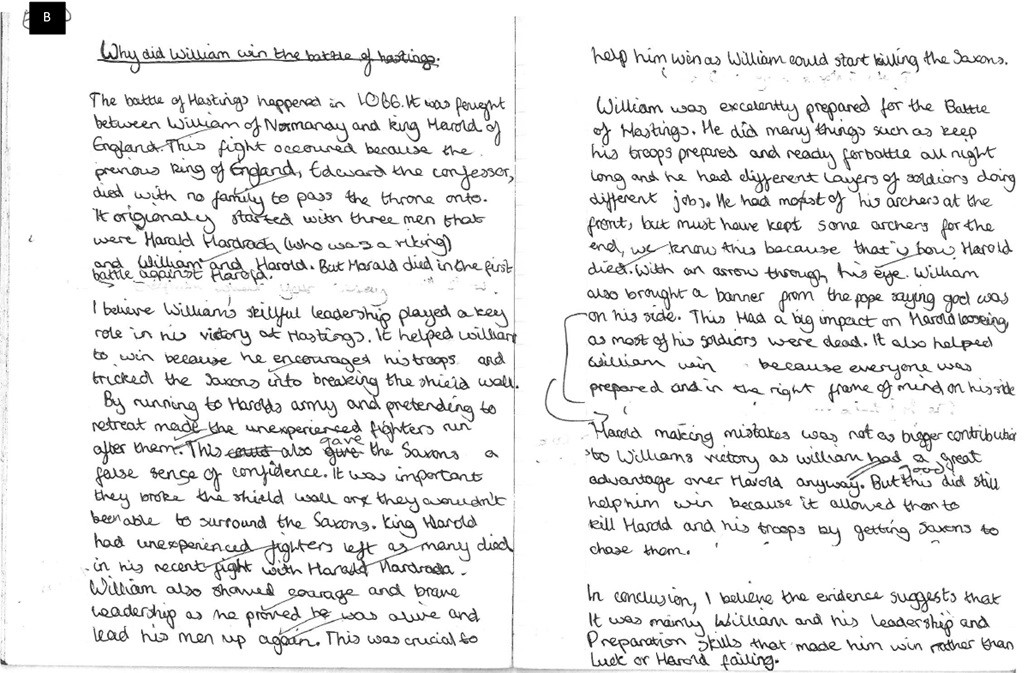

They say seeing is believing so let’s tackle a real life issue. Below are two examples of students’ writing about William’s victory at the Battle of Hastings. These were 40 minute timed essays without notes and done with pupils in Year 7 just before Christmas. All you need to do is work out which “level” each would be given using the second-order linear progression model as your guide.

- Level 3 – Demonstrate an awareness of human motivation illustrated by reference to events of the past

- Level 4 – Understand that historical events usually have more than one cause and consequence

- Level 5 – Understand that historical events have different types of causes and consequences

- Level 6 – When explaining historical issues, place some causes and consequences in a sensible order of importance

- Level 7 – When examining historical issues, can draw the distinction between causes, motives and reasons

Now let’s get to the real issue. What advice might we give to pupil A to “improve” their essay? Simple – “make a point of saying which is the most important cause.” Level six? Tick.

In reality, what I am actually looking for many things in an assessment like this: the pupil’s command of the topic knowledge; their awareness of context (pupil A’s awareness of military tactics and the context of the time is much more developed); their ability to reason causally in history AND of course their ability to engage in the process of constructing an argument. The linear, “skills” progression model narrows the scope of my marking and leads me to focus on only one of these aspects, and erroneously at that! Even at this very basic level the linear progression model is not up to the task.

Now the really big problem with skills-focused, linear models of progression is that, despite all their issues, they are quite seductive. They offer a seemingly simple solution to planning for progression across a year, key stage or school career. Because of this, linear progression models have been used to replace national curriculum levels in many, many schools. Burnham and Brown have written a very clear warning to schools against such an approach in Teaching History Issue 157 (2014, p. 17). I have summarised some of their key "don'ts" here:

- "[Don't] use the levels as they exist or create something largely similar to the levels. The level descriptions were never intended to be used for formative assessment or individual pieces of work. So, don’t try creating a generic linear model of progression that fails to capture the complexity of historical progression and ignores the importance of historical knowledge.

- "[Don't] Use GCSE mark-schemes from Key Stage 3 onwards. Such generic mark-schemes that reduce progress to small steps in a simplistic, linear way will simply encourage more teaching to the test. GCSE mark-schemes are weak models of progression that largely ignore substantive knowledge and the complexity of second-order conceptual development, so will not help pupil progress."

- "[Don't] use a single taxonomy (e.g. Bloom’s) as a structure for assessment...Designing assessments and creating displays about making steps from ‘description’ to ‘explanation’ and ‘analysis’ will be meaningless and confusing, particularly out of subject context."

- "[Don't] use numbers or grades rather than descriptions in an effort to make things easy to do and easy to use. Data has its uses but carefully crafted descriptions will enable you to capture the complexity of subject-specific progression."

VERDICT: AVOID SKILL-BASED LINEAR PROGRESSION MODELS AT ALL COSTS!

Footnote

Now there are some potential uses for linear progression models. As in the maths example at the beginning, linear models of knowledge acquisition can be useful. Planning logically what knowledge we want students to be able to command can be done in a cumulative and even iterative way. We generally call this kind of progression model a curriculum however. A good history curriculum will set out clearly what pupils should be learning at each point in their school history career. An even better one will note which knowledge pupils should be taking with them as they move forward. Even GCSE gets this right as it specifies required knowledge to some extent. Key Stage 3 is vastly different because knowledge is left down to individual departments, or even teachers to select. But select it we must. Devising ways of checking pupils are building their historical knowledge through the Key Stage is actually not hard and could be done simply through formative assessment, quizzing, timelines, synoptic essays, and a range of other means. None of this can happen however without serious thought being given to curriculum design in the first instances.

For an interesting unpicking of these issues in more depth see Micahel Fordham’s blog posts here: http://clioetcetera.com/2014/10/29/assessment-after-levels-dont-reinvent-a-square-wheel

And here: http://clioetcetera.com/2014/04/12/new-curriculum-part-3-planning-for-progression-from-ks3-to-gcse/

References & Useful Reading

- Blow, F., 2011. Everything Flows and Nothing Stays. Teaching History, Issue 145, pp. 47-55.

- Brown, G. & Burnham, S., 2014. Assessment After Levels. Teaching History, Issue 157, pp. 8-17.

- Counsell, C., 2000. Historical Knowledge and Historical Skills: A Distracting Dichotomy. In: J. Arthur & R. Phillips, eds. Issues in History Teaching. London: Routledge, pp. 54-71.

- DfE, 2013. Mathematics Programmes of Study: Key Stage 3, London: DfE.

- Ford, A., 2014. Setting Us Free? Building Meaningful Models of Progression for a 'Post-Levels' World. Teaching History, Issue 157, pp. 28-41.

- Fordham, M., 2016. Knowledge and Language: Being Historical with Substantive Concepts. In: MasterClass in History Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 60-85.

- Lee, P. & Shemilt, D., 2003. A Scaffold Not a Cage: Progression and Progression Models in History. Teaching History, Issue 113, pp. 13-23.

- Lee, P. & Shemilt, D., 2004. 'I just wish we could go back in the past and find out what really happened': progression in understanding about historical accounts. Teaching History, Issue 117, pp. 25-31.

- Seixas, P., 2008. “Scaling Up” the Benchmarks of Historical Thinking: A Report on the Vancouver Meetings, February 14--15. Vancouver, s.n.

- Seixas, P. & Morton, T., 2012. The Big Six Historical Thinking Projects. Toronto: Nelson.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed