I will warn you now, this is a long post. But then again, progression is a complex subject…or rather it is a subject which has been made complex. Please bear with me though, because I think this is fundamental!

If you have not yet read my “primers” on progression, you may wish to do so now.

If you are already familiar with the two aspects above then please feel free to read on...

Over the last week or so I have been marking PGCE trainees’ assessments on planning for progression in history. As I have done this, I have found myself returning to a common theme in my comments; namely that trainees first need to consider WHAT they want pupils to get better at before they start considering HOW they want to achieve this. Where trainees did focus on the substance of history, there was either too much generic focus on the development of historical “skills” and processes (and issue which I will deal with later), or too much time spent on discussing knowledge acquisition and aggregation with little sense of how this contributed to overall historical progression. Knowledge acquisition certainly is a type of progress, but I would argue is insufficient to count for all progression in history. In essence, trainees have found themselves wrestling with history’s twin goals of developing pupils’ knowledge as well as their second-order modes of thinking. Too often they fell down the gap in between.

Interestingly, these confusions were much less evident in work produced by maths trainees. This may be because the maths curriculum specifies a series of substantive concepts for students to master. For example, in understanding algebra, students are asked to “simplify and manipulate algebraic expressions”, to “model situations or procedures by translating them into algebraic expressions”, or “use algebraic methods to solve linear equations in 1 variable” (DfE, 2013, p. 6). As such, maths teachers can help pupils progress to more powerful ideas about maths through a clear content focus. Maths does still have its unifying second-order concepts, “select and use appropriate calculation strategies to solve increasingly complex problems” for example (DfE, 2013, p. 4), but progression in these is can be tied to precise curriculum content. To be fair, this does also come unstuck, as pupils failed to use their second-order ability to apply maths in context in the “Hannah’s Sweets” controversy last year!

A very real confusion

In many ways, the confusion about progression is at the heart of history teaching more generally. Indeed, the recent book "New Directions in Assessing Historical Thinking" (Ercikan & Seixas, 2015) suggests that there are vastly different approaches to understanding historical progression both internationally and within countries and states. This is certainly true of history education in England. There are many reasons for this:

- There is still uncertainty amongst history teachers (and teacher educators??) about the distinctions between substantive knowledge and second-order concepts.

- Substantive knowledge is the stuff of history. This might include: dates, events, names, people and other details. We might also talk about substantive concepts: these are terms like “king”, “peasant”, “parliament”, all of which have historically grounded meanings, but meanings which change over time. It is possible, Michael Fordham argues to talk about pupils making progress in their understanding of such concepts (Fordham, 2016).

- Second-order (or disciplinary) concepts such as, significance, change & continuity, or causation are the ways in which we understand history. They are not the objects of historical understanding but lenses through which we view particular historical knowledge.

- History teachers (and often examiners and other “experts”) are unclear about the relationship between progression, knowledge and second-order concepts. I have covered some of this confusion and how it has played out in my primers (above).

- An excessive focus on pupils’ development in second-order conceptual understanding has led to models of progression which have tended to ignore pupils’ development of knowledge. In the worst cases, such models have argued that what is studied in history does not matter because only second-order concepts (or “skills” as they are often incorrectly called) are transferrable. This is extremely evident in many European and North American attempts to assess aspects of historical thinking as competencies (Ercikan & Seixas, 2015) and in many of the approaches taken in GCSE assessments.

- A focus on the idea of second-order concepts as “skills” to be mastered has exacerbated this problem. Second-order concepts must not be confused with skills. A second-order concept like causation, unlike a “skill” such as essay writing, has no value in its own right, it is merely a means by which we might understand history. Any progression models which try therefore to map out an improvement in second-order conceptual thinking without reference to historical content are doomed to failure.

- The National Curriculum level descriptors were turned into defacto progression models in many schools. Such approaches focused on progression in numerical terms, leading to the problem of students wanting to move from one number to another with little understanding of what this might mean. This in turn led to the creation of generic ladders of progression for pupils to climb. All of these were divorced from historical content, and most bore only a loose connection to second-order conceptual thinking.

- A range of “reputable” sources still insist on publishing materials suggesting ways to make progress in a linear fashion, or reinforcing unhelpful notions of second-order concepts as “skills”. These range from exam boards, to publishers, to inset style courses, not to mention the TES online resource repository.

- There is still a hesitancy amongst history teachers with regard to adopting an approach to history teaching which values knowledge as part of progression. I am going to be blunt about this. Whilst aggregating historical information for its own sake might be seen as problematic (Lucien Febvre once wrote about young people being turned away from the study of the subject because too many historians acted like butterfly collectors, amassing facts with no thought to their application or significance), I firmly believe that developing historical knowledge is a core responsibility of history teachers. We might well argue (rightly) over what goes in the curriculum, but we should all be able to justify what content we teach in terms of its role in developing young people’s historical understanding. If we see knowledge as an unnecessary by-product of a skills education, then we might consider finding a new profession!

I have covered many of these issues in my two primers on progression models above. Here I want to begin focusing on some solutions. How can we begin to unshackle ourselves from the corpse of skill-based, linear progression models?

In many ways I am very drawn to Seixas’ approach (discussed in my primer) of setting out guideposts of historical thinking (Seixas & Morton, 2013) However, I feel that his approach needs to be connected much more closely with pupils’ mastery of the historical content they have studied. We cannot continue down the line taken by some jurisdictions that historical knowledge is not an integral part of historical thinking. In Germany for example, the lack of a national curriculum means that "large scale testing cannot include substantive knowledge about specific events, contexts, and/or interpretations of history. In this aspect [tests] need to be self-contained, meaning that they must offer all the specific context and information needed for fulfilling the tasks." (Korber & Meyer-Hamme, 2015, p.91). Surely, that way madness lies!

In this sense, the second-order concepts must always be taught and assessed connection with the specific historical content. I would therefore talk about a pupil’s understanding of causation in the context of the Civil War, or their appreciation of the significance of different individuals in the abolition of the slave trade. Discussions of progression would therefore need to incorporate descriptions of pupils’ thinking AND their command of knowledge. Some reference would need to be made to their command of the specified curriculum content as a whole. This is certainly the approach which has been taken in Sweden with the introduction of national history testing in 2013. Their approach focuses on the application of substantive historical knowledge to second-order tasks. Crucially, core knowledge is defined to a greater extent at state level, leaving schools to develop weave their own courses and content around this core (Eliasson et al., 2015). In many ways this approach is also the one taken by the new OCR History B (SHP) GCSE, which sets broad topic knowledge, but allows schools to choose the precise content to cover. This is fundamentally an issue of curriculum design for schools to grapple with (OCR, 2016).

- Have clear and logical progression in terms of pupils’ substantive knowledge AND which offer them opportunities to develop their second-order thinking about the subject as well.

- Give students transferable knowledge (that which Counsell (2000) describes as “residual knowledge”) which pupils use to broaden their historical understanding. For example, some of the causes of tension in the Civil War should form useful residual knowledge to understand the causes of the French Revolution. We also need assessments which reward this.

- Clearly define the essential knowledge for pupils to grapple with. This should be in terms of topic knowledge, period knowledge, broader contextual knowledge, and substantive concepts.

- Incorporate assessment approaches which do not favour one aspect of history (second-order concepts) over another (knowledge) and which allow children to be taught a broader domain before focusing in on the assessed topic. Each of the assessments should have a task specific mark scheme, unifying content and aspects of the second-order concept .

- Allow pupils to become better essay writers, or debaters, but which don’t do this at the expense of their understanding of the visceral, human interactions of history, or the bigger narratives (whichever we think these should be).

- Allow progression to be messy!

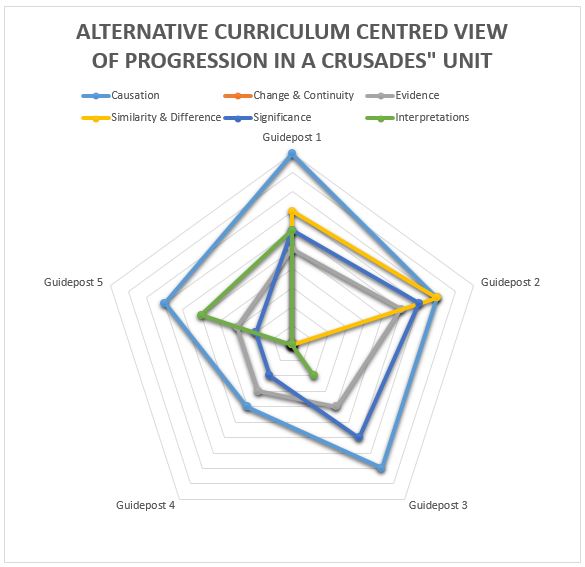

In my primer piece on research-based models of progression I noted that Seixas' approach to progression in historical thinking created a non-linear means of talking about progression. However, using the illustration (right), I also noted that it suggested pupils could master historical thinking aside from historical content.

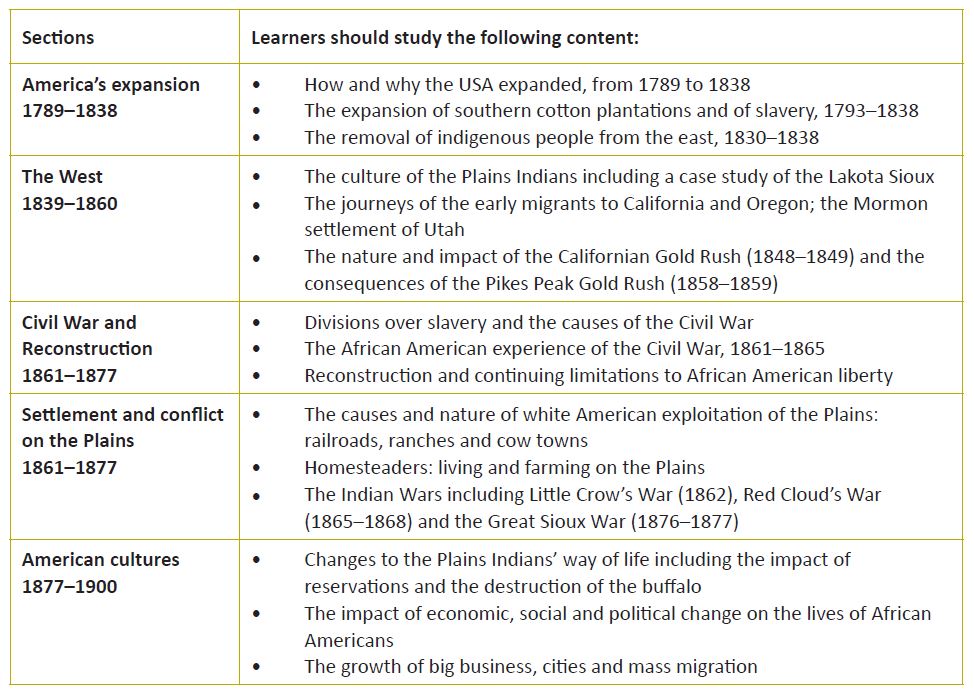

Below I have updated my radar diagram to show how blending Seixas’ work with a carefully designed, and knowledge-rich, curriculum might give a more powerful and historically grounded view of a pupil’s progression in history. This time I am trying to visualise a pupil’s causal thinking across 18 months of teaching and through a number of key assessments. This is based on 3 assessments I completed with the student over the course of the 18 month period. Please note again that this is NOT a reporting suggestion, I am simply trying to visualise what might have been happening in terms of this student's progression in marrying historical thinking with the curriculum. In this example the three assessments got progressively more demanding in terms of their conceptual complexity (where needed) and in terms of the complexity of their content. They were not all formally assessed in the same way.

Assessment 1: Why did William win the Battle of Hastings?

The chart reminds me that in the Battle of Hastings assessment, the pupil had a good knowledge of a wide range of causes and their influence on the outcome of the battle (appropriate to the level I had taught them and connected to the content specified in my scheme of work). It illustrates that they were aware of factors which influenced the battle other than the actions of the main people (again as specified). It also reminds me that this student did a good job of showing how the battle might have gone different ways at different points through their knowledge of Harold’s decision to leave Senlac Hill and William’s, decision not to retreat, and the unfortunate event with an arrow. It suggests that they grasped most of the core knowledge as specified in the scheme of work and in the mark scheme for this assessment. There is a gap around Guidepost 4 as we didn’t discuss unintended consequences as a class. It is therefore little surprise that they do not mention these. I noted this and returned to it at a later point (something which was already planned for in the curriculum).

Assessment 2: How far was Charles I to blame for the English Civil War?

The results of this one are more interesting. First, the chart reminds me that the pupil was able to select a number of relevant causes of the war (as specified in the scheme of work) and effectively show the influence of these in causing the outbreak of war. Second, that they were still managing to see the difference between an underlying and a personal cause and see the influence of both in their work (they are not mistaking “economic reasons” as actors in their own right for example). Third it tells me that they had a stab at bringing in the unintended consequences of Charles’ religious reforms, however they mainly failed to deal with the influence of this, focusing more on deliberate actions. I made a note here to do some more work with the group as they all had a similar misconception and knowledge gap.

Guidepost 1 seems to have gone backwards from Assessment 1. This is an important point and rests on the fact that they had knew and could link a fair range of causes, but they failed to have the full range I might have expected (as noted in the unite of work), missing out for example the arrest of Pym and the more inflammatory actions of Parliament in the run up to war. It also reminds me that their connections between these causes and war were sometimes a little weak. This was a focus I gave in feedback to the student in question, asking them to do some relevant reading and then to answer the following “Could you explain how Parliament’s actions in the 1630s and 40s might have contributed to the outbreak of war?”

Clearly the student had made good progress in their grasp of the historical knowledge connected to their historical thinking about causation, both in this unit and over time. The fact that the assessment was harder in terms of content (and second-order concept) than the Hastings one provides adequate proof of this.

Assessment 3: Why were the people of France revolting? (Not my actual title but it amused me)

This is the one where data managers would be seeing red flashing lights. Here the student seems to have regressed in all areas of their historical thinking. In a linear model this would make no sense because the “skill” would be ticked off as mastered. Here it might be a cause for concern, but it needs more unpicking. So how did I read this assessment result? I knew that the student had the theoretical ability to show mastery in 4 of the 5 guideposts so what could explain the “regression?”

- The first thing I did was to check other pupils’ results. If they were similar, it would have been likely that the assessment was badly pitched, the content was badly taught, or the difficulty of the assessment too great. This was a useful diagnostic tool. As it turned out, other pupils had managed this assessment well, so the issue lay elsewhere.

- Knowing that the issue lay in the history rather than the assessment design, I looked instead for historical explanations for their “failure” in this piece of work. In this case, the chart suggests that the student had only a surface grasp of some of the substantive knowledge about the causes of the French Revolution, this was supported by the knowledge quizzes I had done in the run-up to the assessment and the book work I had marked in the preceding weeks. I also noticed that they failed to transfer some of knowledge from the work we did on the English Civil War, being unable to see the similarities in how absolutist monarchs tried to rule, or the role of religion in conflicts such as these. What this assessment actually showed me was a large knowledge deficit which had prevented the student applying their second-order thinking effectively. I was able to target specific intervention work on the back of this to ensure that the pupil gained a more solid understanding of the transferable knowledge of the French Revolution in particular.

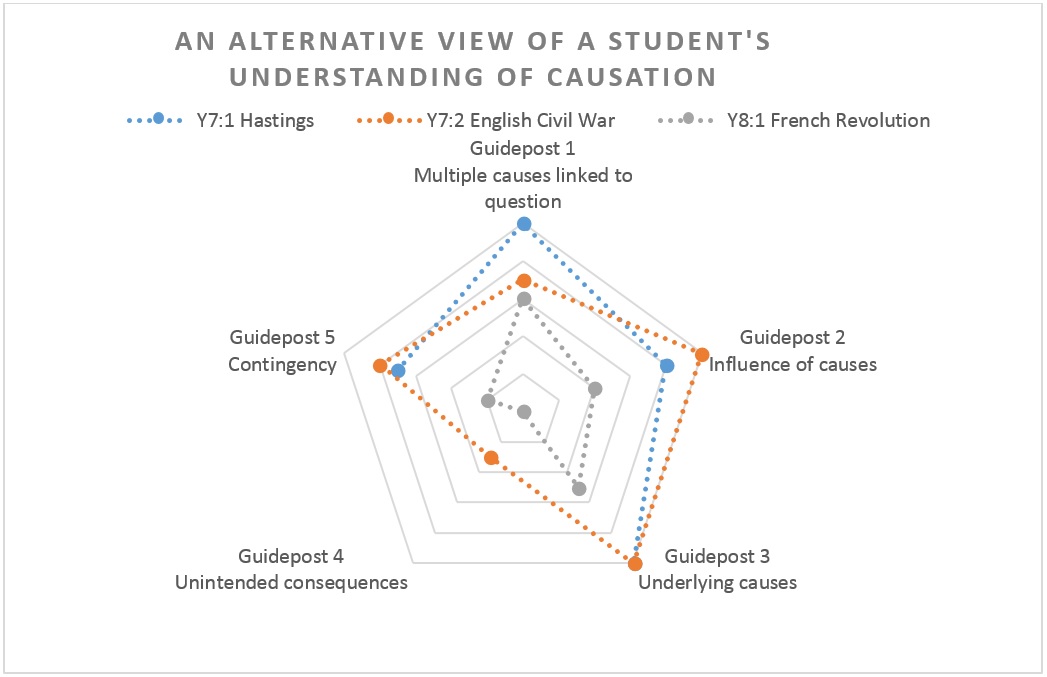

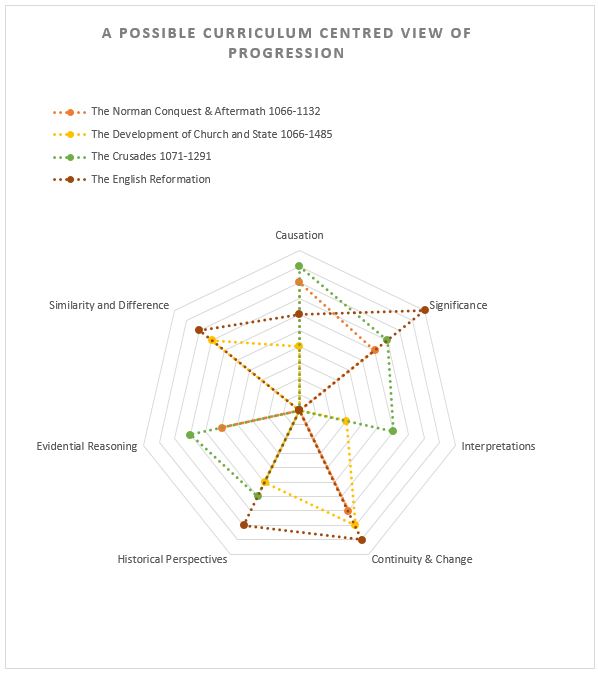

Of course the above visualisation still places historical thinking as the core organising aspect in history. Whilst I think this can be very powerful, it also risks focusing too much on the thinking at the expense of curriculum, as noted in the American and German examples cited previously. In an effort to show this might work with a curriculum core, I have recast the above approach in two alternative ways here. The first uses the broad curriculum as an organising concept (please don't judge this - it was thrown together for demonstrative purposes). The second takes progression in second order concepts and considers this at unit level. As you will see, there are pros and cons to each approach.

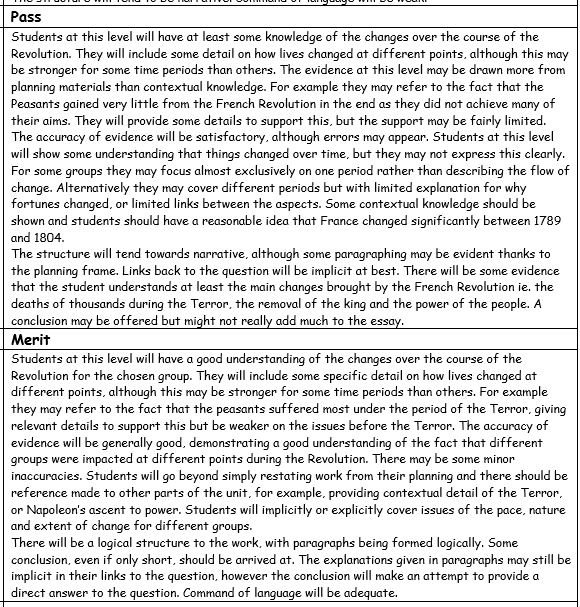

The above examples rest on a number of assumptions about assessment. In this final section I want to spend a little time thinking about how effective progression models can be applied to effective assessment. One of the most powerful ways of assessing pupils’ progression in their historical thinking is through the creation of detailed, task-specific mark schemes. Burnham and Brown talk in more depth about task-specific mark schemes in Teaching History 157 (2014). They note that a good mark scheme should comment on pupils’ application of specific topic and period knowledge to an historical question based on a second-order concept. Their mark schemes also try to assess pupils’ application of processes such as effective communication. In this way they are able to build snapshots of pupils’ developing understanding. I have included one extract from a task specific mark scheme on changes brought by the French Revolution below. Core content for teachers to cover was specified in the scheme of work and we had significant discussion about the levels of knowledge we expected to reward. Of course, students were also rewarded for bringing in relevant knowledge from other areas of the course or those which their teachers developed above and beyond the core. Fordham gives another example of a task specific mark scheme here: http://clioetcetera.com/2014/02/17/beyond-levels-knowledge-rich-and-task-specific-mark-schemes/

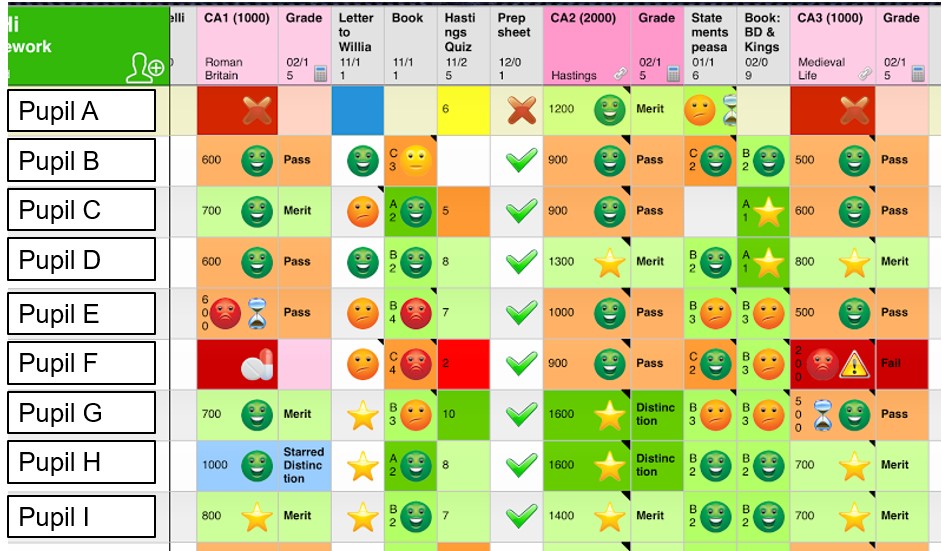

Below is a small sample my Year 7 mark book. It might look a bit bizarre to you, but to me it is rich in information about progression. Take pupil C. They did reasonably well at applying their knowledge of Roman Britain to the question of continuity and change (we were addressing the guideposts of immediate change and thinking about different groups’ experiences of change). Their book work showed a really good grasp of the work we then began on the Norman Conquest, but their knowledge retention was actually quite poor. I sent them off to do some knowledge revision but, according to my notes, they were unable to apply this particularly effectively in their causal work on Hastings. In fact, I noted that they had grasped the conceptual idea that there were multiple connecting causes for William’s victory, but their understanding of what might constitute an advantage in a medieval battle, and the importance of the king as a leader, were strong enough for them to make these links. These are all discussions I was able to have with the student through the many interactions we had as pupil and teacher. It also allowed me to clearly explain to their parent on parents’ evening, that they needed to do some more work revising their knowledge of the Norman Conquest and the nature of life in the Middle Ages. Parents found this surprisingly useful as it gave them something concrete to do with their child at home. NONE of this would have been captured by the grades, 5c, 4b, 4c!

I hope that I have illustrated how we might better address issues of progression in history. For me, the key part is that we need to spend more time considering WHAT it means for students to get better at history. I have argued that this comes down to three things:

- Explaining what improvement in historical thinking looks like (described brilliantly by Seixas & Morton (2012), Lee & Shemit (2003) and a host of others).

- Carefully planning the substantive knowledge pupils will develop through their study of history. Spending time arguing over and creating an effective curriculum for pupils to follow.

- Considering the interplay between these two elements in the curriculum.

Unshackling ourselves from the rotting corpse of linear progression models and really engaging in what it means to get better at history is liberation in its fullest sense. It enables us to focus pupils on history and the historical method. It helps us to apprentice young people in the dispositions of thinking which historians display. God forbid, it may help history to be a subject which pupils enjoy because of its rigour, rather than despite it.

The fundamental link between historical thinking and substantive knowledge also forces us to take full responsibility for the historical content which our pupils learn through the curriculum. We can no longer suggest that the content we choose to teach is irrelevant, or that progression can be considered in isolation from it. Moreover it places important debates over what content we develop back where they should be, at the heart of history teaching. This means considering how the curriculum we choose to pursue contributes in the broadest sense to developing they young people in our care. This will of course vary between contexts to some degree, but it does not mean bowing to a solely uncritical and antiquarian approach to the past in which we narrate "events whose only connection is they happened around the same time: eclipses, hailstorms and the sudden appearance of astonishing meteors along with battle and the deaths of kings and heroes." This, Marc Bloch describes as like "the garbled observations of a small child." (Bloch, 1949/1991, p.19). Nor should we cram our curriculum with simple opportunities to make judgements about the past "in order that the present might be better justified or condemned." (Bloch, 1949/1991, p. 26) Rather we need to create a curriculum which genuinely helps in our pursuit of a more historical goal, namely, to deepen our understanding of ourselves within time, and all the complexity that entails.

Crucially, freeing ourselves from the dead corpse of generic approaches frees us to be what we signed up to be: teachers of history. I want to finish with a final reflection from Bloch who, during the Second World War, was grappling with what it meant to be an historian in the modern world. I think his words are relevant to us as history educators today as well.

“Either all minds capable of better employment must be dissuaded from the practice of history, or history must prove itself as a form of knowledge…I would should like professional historians [and history teachers?]…to reflect upon these hesitancies, these incessant soul-searchings of our craft. It will be the surest way they can prepare themselves, by deliberate choice, to direct their efforts reasonably. I should desire above all to see ever-increasing numbers of them arrive at the broadened and deepened history which some of us – more every day – have begun to conceive.” (Bloch, 1949/1992, p. 8-15)

References & Useful Reading

- Bloch, M. 1949/1991. The Historian's Craft. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Blow, F., 2011. 'Everything Flows and Nothing Stays'. Teaching History, Issue 145, pp. 47-55.

- Brown, G. & Burnham, S., 2014. 'Assessment After Levels'. Teaching History, Issue 157, pp. 8-17.

- Counsell, C., 2000. 'Historical Knowledge and Historical Skills: A Distracting Dichotomy'. In: J. Arthur & R. Phillips, eds. Issues in History Teaching. London: Routledge, pp. 54-71.

- DfE, 2013. Mathematics Programmes of Study: Key Stage 3, London: DfE.

- Eliasson, P., Alven, F., Axelsson Yngveus, C., & Rosenlund, D., 2015. 'Historical consciousness and historical thinking reflected in large-scale assessment in Sweden'. In: K. Ercikan & P. Seixas eds. New Directions in Assessing Historical Thinking. New York, Routledge, pp. 171-182.

- Ercikan, K., & Seixas, P., 2015. New Directions in Assessing Historical Thinking. New York, Routledge.

- Ford, A., 2014. 'Setting Us Free? Building Meaningful Models of Progression for a 'Post-Levels' World'. Teaching History, Issue 157, pp. 28-41.

- Fordham, M., 2016. 'Knowledge and Language: Being Historical with Substantive Concepts'. In: MasterClass in History Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 60-85.

- Korber, A., & Meyer-Hamme, J., 2015. 'Historical thinking competencies, and their measurement: challenges and approaches'. In: K. Ercikan & P. Seixas eds. New Directions in Assessing Historical Thinking. New York, Routledge, pp. 89-101.

- Lee, P. & Shemilt, D., 2003. 'A Scaffold Not a Cage: Progression and Progression Models in History'. Teaching History, Issue 113, pp. 13-23.

- Lee, P. & Shemilt, D., 2004. ''I just wish we could go back in the past and find out what really happened': progression in understanding about historical accounts'. Teaching History, Issue 117, pp. 25-31.

- Seixas, P., 2008. “Scaling Up” the Benchmarks of Historical Thinking: A Report on the Vancouver Meetings, February 14--15. Vancouver, s.n.

- Seixas, P. & Morton, T., 2012. The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts. Toronto: Nelson.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed