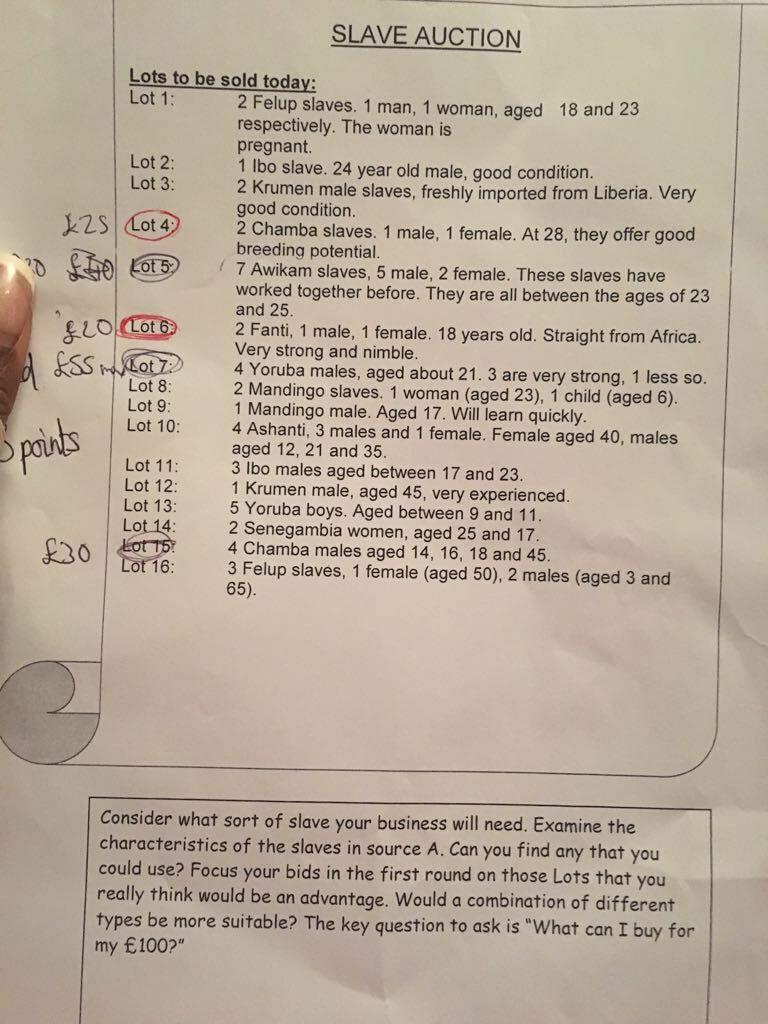

The “slave auction”

Reading the title of this, I hope most people would be baulking already. However, in the last five years, I have heard of this kind of lesson being used in multiple history departments and the image above is not invented but actually came from a grammar school in the South East. Just as with the Holocaust example I gave last time, this type of activity can end up being done in multiple topic areas, but effectively involves role-playing an extreme power imbalance.

The reasons departments persist with “lessons” like this one are usually vaguely couched in terms of empathy, and the need to clarify complex concepts like chattel slavery. However, more often than not they are promoted for their “interactive”, or “engaging” elements. Indeed, one non-historian described seeing such a lesson to me once as being “a good, fun way to get across a difficult idea.”

- The concept of people owning, buying or selling others is abhorrent and challenging on a moral level. However, it is not complex. A whole lesson to communicate this basic notion seems unnecessary, especially with the associated issues of this particular lesson.

- On a moral- and social- level the concept of running an auction does not encourage empathy, but ends up reinforcing prejudices and perpetuating the moral underpinnings of the original system. I cannot think of a single instance of these kinds of lesson where one or more students hasn’t found fun in the bidding wars, without considering the implications of this. Indeed, such power experiments would almost certainly be denied ethical approval for a researcher. More than this, real, historical slaves are denied their voice simply by the fact they are being “played” by modern child-actors with no concept of the lived realities of the people they supposedly represent. And it doesn’t matter if you make all the kids with red ties, or blue eyes, the “victims”, the problems remain.

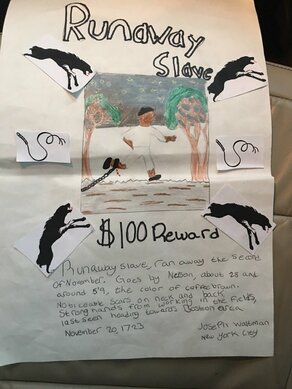

- I cannot think of a good historical reason to teach the horrors of slavery via this means. In fact the whole topic area is usually awash with poorly conceived ideas (see the "create a runaway slave poster" task above for example)

Of course, I am not saying for one minute that history teachers should ignore, or underplay the extreme trauma of slave auctions. But we need to be able to trust that our students can find the same horror in the archival details, the records, the accounts, which presumably so incensed us when we first heard or read them.

If we really want students to see the impact of slavery on people, then there are many accounts written by escaped slaves which are far more visceral and poignant for being true. An enquiry such as “What can the life of Charles Ball (or Mary Prince, or any number of others) reveal about the horrors of slavery” places a real person at the centre of the study. It also allows us to see the ways in which Ball challenged, and was forced to accept the realities of slavery – making him an key actor in the story.

Another approach might be to ask: “How did people survive despite slavery?” Such a question draws very much on the work of Edward Baptist, who makes this one of his central questions in his excellent “The Half Has Never Been Told” (2014). Such an approach would allow a focus on the ways in which the slave system attempted to reduce people to units: so many heads or hands; but how those kept in slavery resisted through the communities they built, stories they told, and lives they continued to live in adversity. I challenge you for example to read Baptist’s retelling of the story of the enslaved Joe Kilpatrick and his daughters, and not be moved to tears with both sadness and pride.

More than anything, teaching about slavery, or the Holocaust, or any other controversial topic requires a deep and fundamental engagement with what we hope to achieve. What is the role of history when discussing the slave trade or genocide? Should the purpose of teaching slavery be to shock the students, or help them appreciate that slaves were real people, with real lives, who lived just like any other historical actors as part of their moments in time? Should we tell students about the Holocaust so that they are moved to tears, or to help them understand how such a cataclysmic event grew insidiously over time, rather than being a strange anomaly of the 1930s? Whatever our answer(s), we need to hold these things at the centre of our planning throughout. Here Peter Kenez wrestles with the similar issue as he begins his book on the coming of the Holocaust.:

I hope you have found this blog series helpful. As ever, I would love to hear your thoughts. Have I missed out anything crucial (probably)? Or are there particular historical topics which make you equally worried? Let me know in the comments below.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed