The crisis

First a very brief overview of the specific crisis this summer. During the coronavirus lock down, formal examinations of pupils were cancelled by the DfE. A decision was taken to ensure students were still graded despite not sitting exams (we could discuss the problems in this too, but there is no space here). The statement from Gavin Williamson (below) really should have raised more questions and scrutiny at the time. The notion that grades for 2020 would be indistinguishable from other years despite students not sitting exams, or that “grading” in the usual way was the best outcome for students, were assumptions which should have been more robustly challenged. However, too many were unwilling to think through the potential consequences or were blinded by their faith in what they believed to be a robust and functioning examinations system which achieved fairness in normal years.

Once grades were submitted, Ofqual, in line with the DfE’s request, set about standardising the imagined examinations. A controversial algorithm was developed which redistributed the CAGs received by students according to the historic performance profile of the school. You can read much more on this process in the blog by FFT Education DataLab.

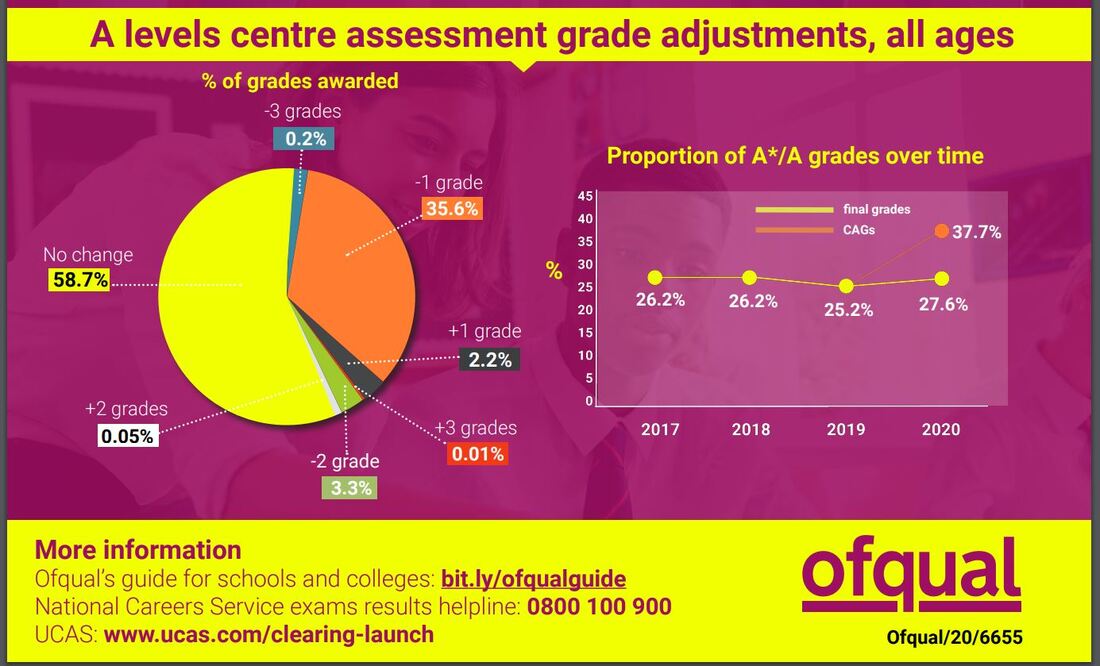

The result of all this was that when students received their grades on 13th August, many were shocked by what they found. Despite the many reassurances of fairness from the DfE and Ofqual, only 58.7% of centre assessed grades were retained. A tiny handful of grades (2.2%) were upgraded by one, but over 35% of grades were reduced by one and a further 3.5% by two or more. Naturally, this caused outrage.

The result of teachers’ deliberations over grading was that Ofqual were provided with exactly what the regulator asked for: a fair assessment of the abilities of students based on teacher evidence and judgement. Of course, the grade distribution was much more positive that the distribution would have been had exams been sat. This is because during a normal exam season the grade boundaries are set to maintain distributions in line with previous years. In other words, an A Grade does not exist until all the exams have been marked. By inverting that process Ofqual created a huge issue. Given their instruction from the DfE was to keep the grading as close as possible to previous years to prevent grade inflation, major changes to CAGs were required. Arguably it might have been more transparent if Ofqual had provided schools with their allocated grades beforehand i.e. “based on historic data you can award 6 A grades; 26 B grades” etc.

The issue of being fair to students and keeping grade inflation in line with historic figures was always going to cause problems. It is of course perfectly true that the same proportions of grades were given out as in previous years (indeed there was a small increase in awards at the top end). In a normal year however, the differentiation between students getting an A or a B grade in a subject would have been determined by the actual performance of that student in their exams, not by a system of statistical manipulation based on a school’s historic performance. As one commentator put it, students were judged by the ghosts of students past. The process in effect became a lottery based on historic data and teacher ranking (itself a problematic process, especially when teachers had ranked with little knowledge of how exactly this was to be used).

The outrage over results this year is perfectly understandable. However, many commentators are prone to assume that it is somehow unique. But the crisis did not appear from the ether in March 2020, rather it was a symptomatic outpouring of a much more pernicious disease. The reality is that our exams system has been eating itself away with its own contradictions and injustices while Ofqual, the DfE, and many others carry on as if nothing is wrong. We cannot ignore it any longer. Unless we admit there is a problem there will be no cure.

This year’s results have grabbed the headlines because students were affected across the board and through no evident fault of their own. Yet equally outrageous miscarriages of fairness have been occurring in many subjects at GCSE and A-Level for years.

I could list many example here of the ways in which specifications are poorly set and defined; how teaching time limits are poorly monitored at GCSE; how exams have driven content in some schools for far too long; how the norm referencing approach ignores what students can do in favour of how they rank against others in their national cohort; or how the exam support system has encouraged teachers to game results and push their pupils up in those rankings. In this blog though I want to focus on the sickness at the heart of the marking and grading of exams.

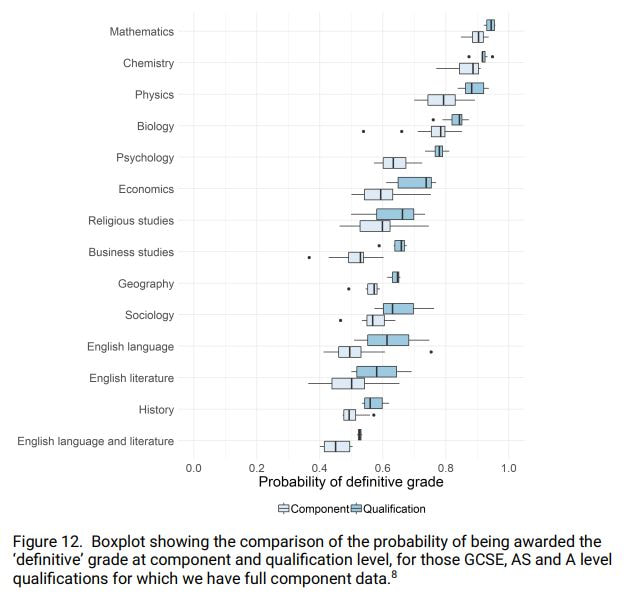

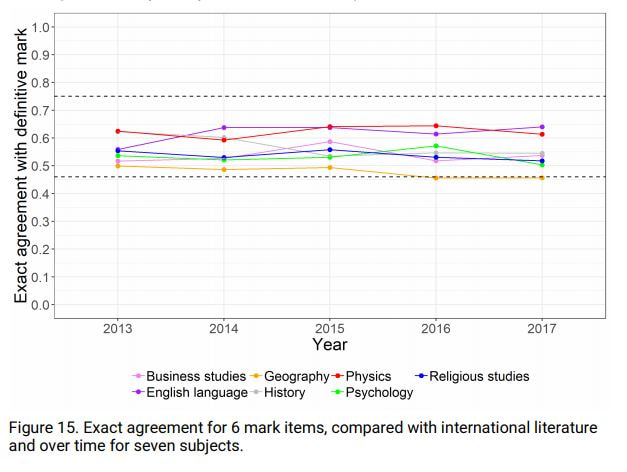

In 2018 Ofqual published research exploring the reliability of marking in reformed GCSE and A-Level examinations. They explored how far markers were in line with the “definitive marks” awarded by the principal examiner, as well as how far markers were in line with the “definitive grade” awarded by the principal. What they found in some subjects was just as shocking as the awarding crisis we have just experienced.

The crisis of 2020 may well be a blessing in disguise. We can no longer pretend that the exams system in the UK is fit and healthy. But we must ensure that treatment comes soon. We cannot continue to drag the sick-man on still further. To do so would be to fail yet another generation of young people.

Follow-up reading

For more on the marking issues noted in this blog please read my previous blog, “The Gilded Age”.

For some thoughts on the purposes of examinations and the issues of norm referencing see: “Searching for Gold”.

And for some musings on where we might go next see: “After the Gold Rush”.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed