Linear progression models are riddled with problems. In this post, I want to focus on one response to the confusions created them: research-based progression models. Let me be clear from the outset, research-based models of progression were not designed as a replacement for National Curriculum levels, rather to address their myriad shortcomings and help teachers to really get to grips with what progression in history looks like.

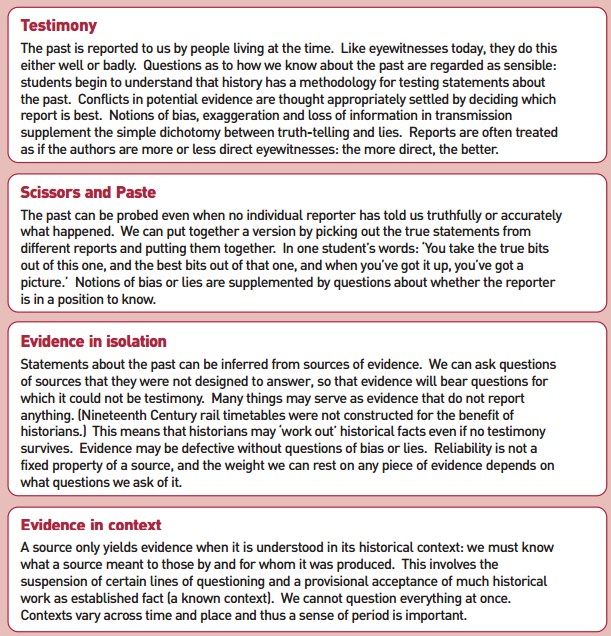

The best thing to do to understand research-based models of progression is to read Lee and Shemilt’s seminal article in Teaching History 113, “A scaffold not a cage”. Research based models differ from linear models because they take students’ work and understanding as a starting point to describe what improvement in history actually looks like. In the above article, Lee and Shemilt offer some descriptions of what pupils’ thinking about historical evidence looks like. They then divide this into “stages” of development. The upper four stages of their model are given here.

Research-based models such as this are powerful as they actually describe what students’ thinking in history looks like, rather than relying on vague and generic assertions as in the linear models. They are very good at helping teachers to identify the gaps in pupils’ thinking, their misconceptions, and where they might sit in terms of the progression model.

Research-based models of progression have many uses:

- They can help teachers to hone in on particular misconceptions held by students about second-order concepts. Teachers might then be able to decide on appropriate actions to overcome such misconceptions in class, feedback, or planning.

- They might enable teachers to assess where pupils are in their historical thinking in a descriptive manner. For example, one might note that a child was unable to use evidence in context. Of course, the follow question would have to find out whether this was an issue of understanding the concept of evidence, or simply a lack of relevant contextual knowledge.

- They might be used to show children grasping more complex ideas and therefore progressing in their historical thinking. Teachers might have a mental note, or indeed a markbook note, describing each pupil’s demonstrated abilities and misconceptions in particular second-order concepts.

- Even though they define a number of stages, these are not evenly spaced, nor do they apply universally to the thinking of all children. They would therefore be less useful as universal measures of pupils’ thinking.

- Because they are shown in stages, teachers can confuse these for logical steps of progression. Lee and Shemilt (2003) are at pains to point out that it would make little sense for teachers to try and use these as a ladder to climb, suggesting that they might offer a means to identify where students are. However, the seduction of a set of linear steps is often too much for many school data managers!

- There is still no real mention of the application of such modes of thinking to historical knowledge. That is to say, a pupil may move to stage 7 in their thinking about historical evidence when studying the slave trade, but only attain stage 6 in their later work on the Industrial Revolution. This could suggest they have regressed in their thinking, or it might suggest that they lack the contextual knowledge to hit the top band.

Rethinking research-based models of progression: the guidepost approach

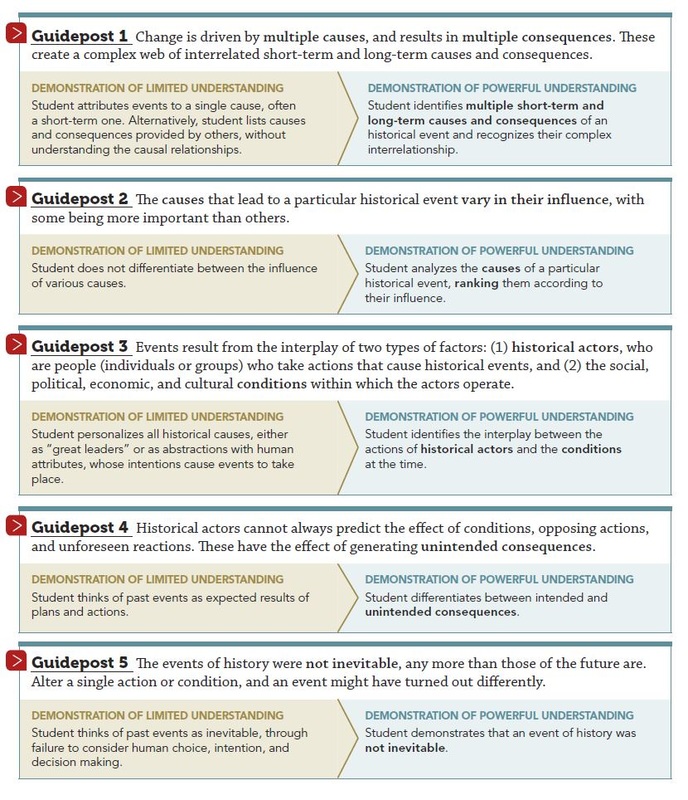

An interesting and very relevant variation on research-based progression models has come out of the Canadian Historical Thinking Project. Peter Seixas takes the idea of progression in historical thinking and makes a fundamental shift in how we might use it as a guide to help pupils progress. Instead of creating a series of levels, Seixas identifies a set of guideposts which he argues represent gold standards for pupils to attain in particular second-order concepts (Seixas & Morton, 2012). He also goes on to identify a number of “misconceptions” students might have which prevent them from moving towards these guideposts. An example of his work on causation is given below and a sampler of his work on significance can be found HERE.

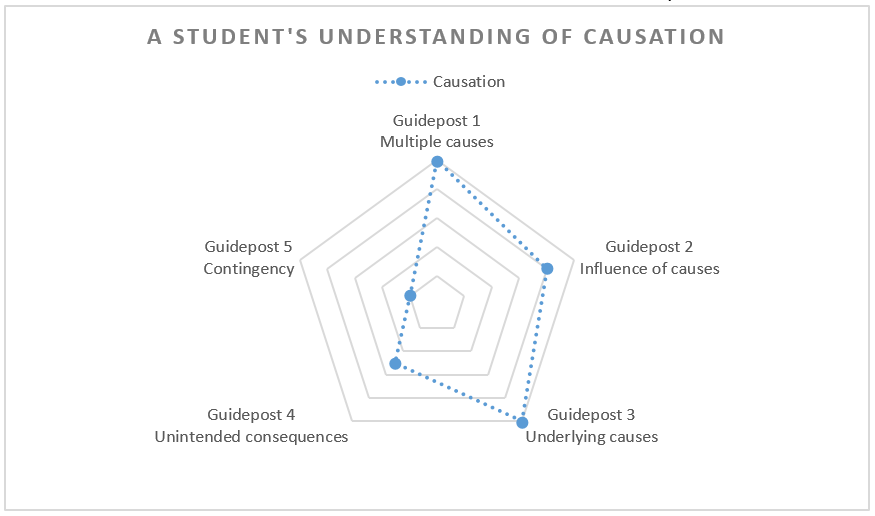

Importantly, Seixas argues that the conceptual guideposts non-linear and therefore not designed to be split into smaller steps. The hallmark of progress is that students overcome misconceptions and move towards gold standards. As such, pupils’ progression in Seixas’ model might looks less like a line graph and more like a radar chart (see below). In this visualisation I have tried to illustrate how Seixas’ approach helps us to see where pupils are developing more powerful ideas and overcoming misconceptions in relation to the particular guideposts of causal reasoning. We would be able to build similar visualisation about their abilities in other second-order concepts as well.

- To set clear, gold standards for pupils’ historical thinking, un-muddied by attempts to create hierarchies of such thinking.

- To help design lessons to deal with pupils’ misconceptions about aspects of second-order concepts.

- To identify targets of historical thinking to frame sequences of work. For example, a teacher may plan a small unit around the idea of unintended consequences in the outbreak of the English Civil War.

- To create assessments which have a meaningful appreciation of what pupils’ responses might look like and to create appropriate mark schemes for these.

- To give an overarching structure to curriculum – planning to overcome misconceptions in all second-order concepts over the course of three, five, or even seven years.

- Tom Morton then spends some time discussing activities which might help move pupils to overcome their misconceptions and develop more powerful ideas in the rest of the “Big Six”.

Not quite free yet!

However, there are still some issues with Seixas’ approach. The most important of these is that it does not recognise fully that a student’s mastery of a second-order concept, such as causation, is contingent on their application to particular historical contexts. That is to say, it is not possible to master the concept of causation in isolation. Historical causation is only relevant in as far as it is applied to historical situations. Seixas does note that “Historical thinking does not replace historical knowledge: the two are related and interdependent.” (2008, p. 6). However, the guideposts approach to historical thinking does not fully engage with this issue (nor again do they attempt to).

Let us imagine I managed to persuade the eminent historian of the Soviet Union, Martin McCauley to write me an essay on the causes of the collapse of the Union. I am sure he would write me an outstanding piece, showing a deep knowledge of the guideposts of causal thinking outlined above. However, if I asked him to write me a causal explanation of the collapse of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, he might do slightly less well (to be honest he might be an expert on this also – I have no idea!). The difference of course would be his knowledge. Whilst he would clearly know that a good explanation would deal with inevitability, unintended consequences, underlying causes, and so on, his knowledge would not necessarily allow him to write such an explanation.

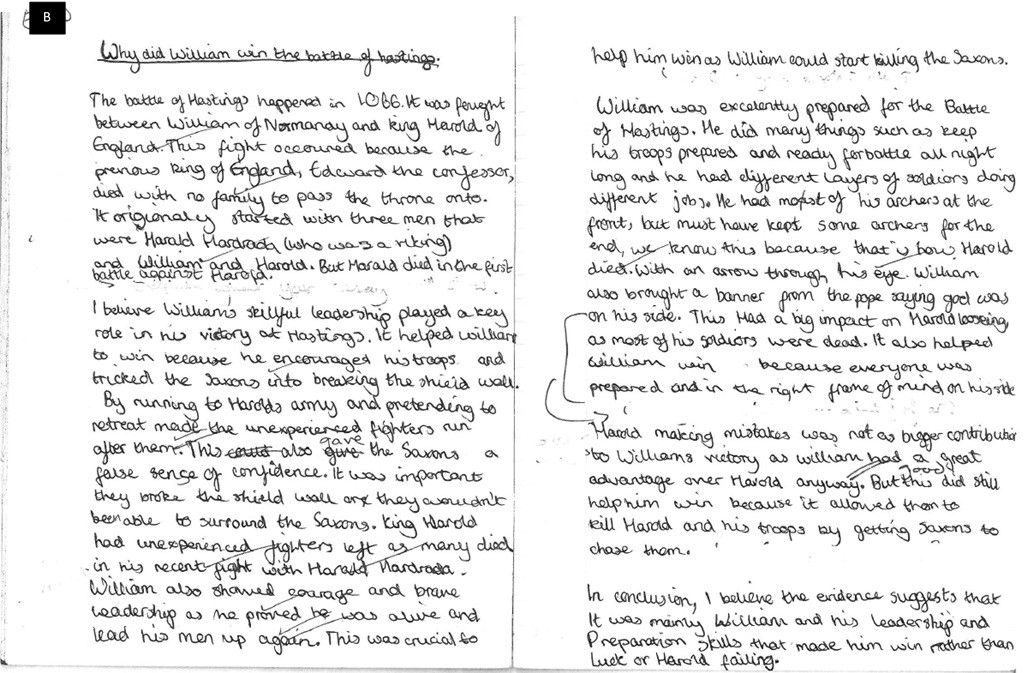

Why should it be any different for children? A student might display excellent understanding of all five causal guideposts in a piece of work in Year 7 on William’s victory at the Battle of Hastings, but fail to show the same mastery in Year 8 when discussing the abolition of the slave trade. This would not necessarily show that they had regressed in their understanding of the second-order concept, but rather that they were unable to apply it fully to the context of Abolition. This would most likely be an issue connected with my mastery of the substantive knowledge of the slave trade. It would focus our attention as teachers on the knowledge deficits we needed to fill. By the same token a causal explanation completed in Year 7 on the reasons for the First Crusade, one completed by a Year 10 and one completed by a Year 13 might well all hit all guideposts for causation, but would hopefully differ in the complexity of the content they commanded. Again, this is a matter of knowledge.

However I do think that the guideposts approach to second-order understanding has a lot of power. I will come on to how we might address the disconnect between it and substantive knowledgde in my next post.

- Blow, F., 2011. Everything Flows and Nothing Stays. Teaching History, Issue 145, pp. 47-55.

- Brown, G. & Burnham, S., 2014. Assessment After Levels. Teaching History, Issue 157, pp. 8-17.

- Counsell, C., 2000. Historical Knowledge and Historical Skills: A Distracting Dichotomy. In: J. Arthur & R. Phillips, eds. Issues in History Teaching. London: Routledge, pp. 54-71.

- DfE, 2013. Mathematics Programmes of Study: Key Stage 3, London: DfE.

- Ford, A., 2014. Setting Us Free? Building Meaningful Models of Progression for a 'Post-Levels' World. Teaching History, Issue 157, pp. 28-41.

- Fordham, M., 2016. Knowledge and Language: Being Historical with Substantive Concepts. In: MasterClass in History Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 60-85.

- Lee, P. & Shemilt, D., 2003. A Scaffold Not a Cage: Progression and Progression Models in History. Teaching History, Issue 113, pp. 13-23.

- Lee, P. & Shemilt, D., 2004. 'I just wish we could go back in the past and find out what really happened': progression in understanding about historical accounts. Teaching History, Issue 117, pp. 25-31.

- Seixas, P., 2008. “Scaling Up” the Benchmarks of Historical Thinking: A Report on the Vancouver Meetings, February 14--15. Vancouver, s.n.

- Seixas, P. & Morton, T., 2012. The Big Six Historical Thinking Projects. Toronto: Nelson.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed