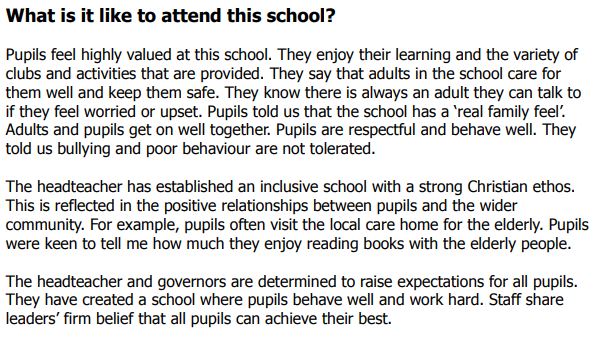

Keegan has not done much to outline her position on education reform yet, however she has stated that she intends raise ‘quality’ across the system by focusing the needs of those in comprehensive schools. At the very least, this hints at a social justice agenda involving all schools – a distinctive break from the grammar school focus of many of her predecessors. Indeed, she seems to be taking a similar tack to former (and now current) Schools Minister Nick Gibb, who described comprehensive schools as ‘engines of social mobility’.

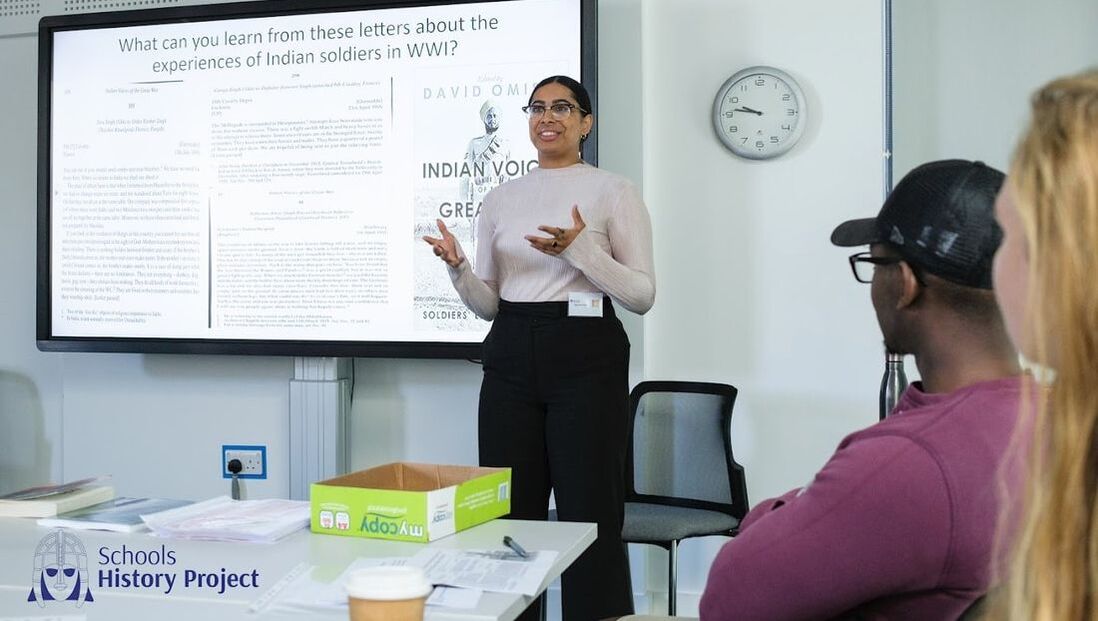

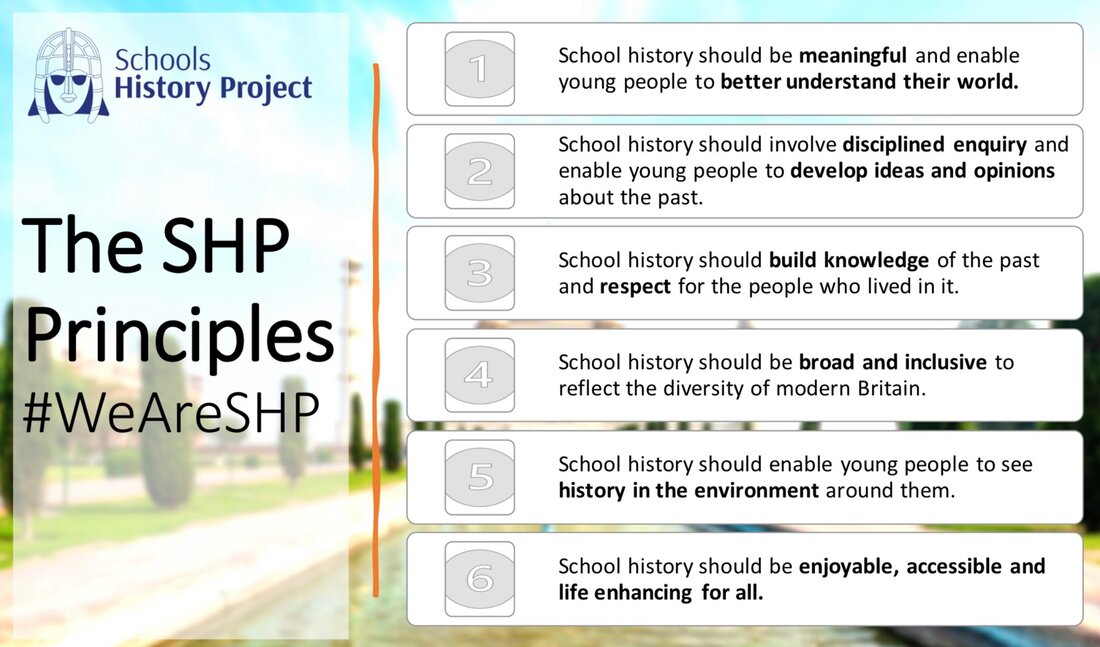

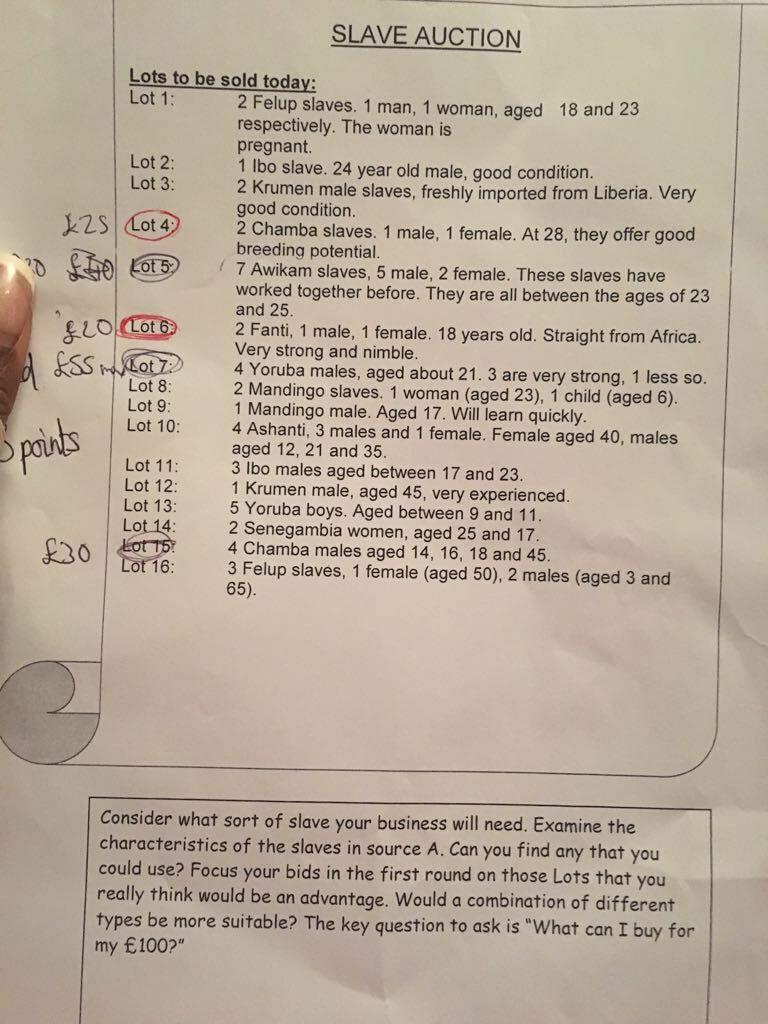

But how does Keegan intend to improve school standards to enable this social mobility agenda? The return of Nick Gibb I think gives the strongest indication of Keegan’s likely approach, not least because she described Gibb as having done a ‘brilliant job’ since 2010. If this is true, then it is likely to mean a continuation of centrally imposed, curriculum-focused reforms. In this blog I hope to highlight the limits of continuing in this manner and, with reference to the history curriculum, and using the work of the Schools History Project as an example, suggest some alternative means to enact meaningful change in the education system.

(If you’d like to know more about the work of the Schools History Project, please do sign up here to receive updates on upcoming projects.)

Improving ‘quality’ AND doing justice?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed